- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

|

Blood testing of vaccinated and non- vaccinated Rota birds.

As discussed in the last Journal I was keen to run some biochemistry /haematology profiles on vaccinated and non –vaccinated birds to see if there was any difference after exposure to Rota virus. To run a blood profile is quite expensive and so we were restricted to running 6 blood profiles. Three VHA lofts had reported symptoms in their birds consistent with a Rota virus infection. Droppings had been collected from each loft and forwarded to Agribio for a Rota virus PCR (DNA) test. The 3 lofts were each confirmed with having a Rota virus infection. Four weeks were allowed to pass. I then travelled to each loft and collected blood from 2 birds at each loft. The blood was then forwarded to IDEXX laboratories for biochemistry and haematology testing. We therefore had 6 samples, two from non- vaccinated birds, 4 weeks post Rota exposure ( bird IDs 18520 and 18540 ) and four from vaccinated birds ( bird IDs – 8210. 8188, 16, 6833) also 4 weeks post exposure. The complete profiles are included in this article. Bird numbers are in the top left hand corner. Fanciers will see that there are many changes in the blood profiles. To discuss the clinical significance in detail of all of these is not appropriate in this setting however if fanciers are particularly interested they are welcome to contact me privately. I am happy to explain what each change means. Fanciers can also refer to pages 42 and 43 in my book “The Pigeon” for some explanatory notes. Fanciers should however look at and compare the AST values . Rota virus targets the liver and bowel wall. AST is an enzyme that is released into the blood circulation when cells in these areas are damaged. Essentially the cells rupture, release their contents, including AST, and the lab technicians then measure this amount of AST in the blood . The higher the AST value, then the greater is the amount of cell damage and inflammation in these areas. In health the AST value should be between 45 and 123 . The 4 lowest AST values are in the vaccinated birds ( 2 are within normal range, 105 and 119, and 2 are not significantly elevated, 124 and 145). The 2 highest are in the non- vaccinated birds and these are significantly elevated ( 188 and 296 ). These results suggest that vaccination does have a protective effect on the liver and bowel of birds that subsequently are exposed to Rota virus. It is reasonable to assume that vaccinated birds with little or no internal damage are more likely to make good race birds than non- vaccinated birds that are exposed to Rota virus and suffer internal damage as indicated by these blood tests. I would personally like to thank John van Beers, Paul Gardiner and Ergun Avci for entrusting their birds to me for testing. It would be interesting to further test these birds to monitor their ongoing values, in particular to see if the liver damage is reversible with time. Unfortunately, however, we have no funding. I have paid for these PCRs and blood profiles out of my own pocket. I am however happy to do further testing if funds become available. Beware Social Media One morning in late July I had two prominent VHA members contact me about one hour apart. Someone had posted on Facebook that “Dr Angela Scott from South Australia Biosecurity has stated that the current vaccines do not work on the new PMV virus in South Australia”. The post sounded authoritative and definite. Obviously they were concerned about a new PMV strain and an ineffective vaccine. Dr Angela Scott is a veterinarian that now works at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) in Geelong, Victoria but at that time was working at Primary Industry and Regions South Australia (PIRSA). The comment seemed strange to me and so I googled PIRSA, rang them, introduced myself and was connected to Dr Scott. She was concerned that her name had been used in this way and said “ I would never say that, I am well aware of the effective of the PMV vaccine”. She went on to say that working primarily in the poultry industry as she does, that “the poultry industry could not operate without effective vaccines because of large vulnerable populations”. She thought that she was able to identify the pigeon fancier who made the post. Apparently the fancier had been having health problems and deaths in his pigeons. Some of the birds had been presented for diagnostic work to PIRSA. Testing showed the birds had PMV. The fancier had advised that he had vaccinated them. Dr Scott explained to me ,that she had spent a lot of time on the phone with the fancier and in the end had referred him back to his local veterinarian to work through his vaccination protocol to hopefully identify where he was going wrong. I rang the fancier concerned. He confirmed that he had indeed made the post on a pigeon forum site. For a new strain to be identified it would need to have its genome sequenced and then this sequence compared and found to be significantly different from the known strain. This has not been done. Also, even if this had been done and there had been a significant number of mutations or viral re-combinations occur so that the genome had become different, it would still be largely the same and so the vaccine would still be expected to “work”. We do not need to have the discussion again about the use and effectiveness of the PMV vaccine. La Sota based vaccines, like those available in Australia have been used by thousands, if not millions, of fanciers around the world for literally decades now to safely protect their birds against PMV. In addition, the actual vaccine available in Australia has been extensively trialed in Australia and has been shown to be safe and effective. Also, each further batch produced has to pass a number of quality control measures prior to being cleared for release and sale. The efficacy of the vaccine is beyond doubt. Just why the fancier chose to put this statement on social media remains unclear to me. He did give me permission to mention his name but I have chosen not to here. The important message is that fanciers need to critically assess material that is placed on social media and preferably should check information with a recognised veterinary authority. Highly pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak in Victoria Much of the following information is from the Agriculture Victoria website. On Sunday 2nd August Victorian veterinarians received a biosecurity alert from Agriculture Victoria. There has been an outbreak of highly pathogenic Avian Influenza H7N7 at a free-range egg farm, at Lethbridge, near Geelong. Agriculture Victoria is responding to the incident. Avian Influenza is a serious disease of poultry, and can cause a high mortality rate in production birds. This disease was reported when a drop in egg production was observed, and high bird mortality rates occurred in one of the poultry sheds. Samples were submitted to Agriculture Victoria on 29 July 2020 where they tested positive for Avian Influenza H7. The CSIRO’s Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness confirmed the disease as highly pathogenic Avian Influenza H7N7 on 31 July 2020. How is Agriculture Victoria responding. The affected property has been quarantined and depopulated. Movement controls are in place to stop any birds, eggs and equipment from leaving the premises. A Restricted Area of about 10 k radius is in place around the property. Agriculture Victoria will be in contact with property owners in the vicinity of the infected property and will conduct further surveillance and sampling of domestic birds in this area. A larger Control Area across a wider area, about 80 km wide, extending up to Ballarat, has also been created. Control of movement within both the Restricted and Control areas depends on the risk. On the 7th August a second outbreak was detected in a nearby property. Australia has previously had a small number of outbreaks of H7 Avian Influenza. These were all quickly and successfully eradicated. Human Health. The H7N7 virus is not a risk to the public as it rarely affects humans unless there is direct and close contact with sick birds. About Avian Influenza. Avian Influenza (AI) is a highly infectious viral disease of birds which occurs worldwide.. All Avian Influenza viruses are members of the family Orthomyxoviridae. The influenza viruses of this family are categorised into types A, B, C or D, and only influenza A viruses have been isolated from avian species. Influenza A viruses are further divided into subtypes determined by haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) antigens. At present, 18 H subtypes and 11 N subtypes have been identified. Each virus has one of each subtype in any combination. There are many combinations of subtypes (strains) of avian influenza virus that cause infections of different severity. These range from low pathogenic or mild strains (causing ‘low pathogenicity avian influenza or LPAI), to highly pathogenic strains that are associated with severe disease and high mortality in poultry (highly pathogenic avian influenza or HPAI). H5 and H7 strains can be highly pathogenic. Chickens, ducks, geese, turkeys, guinea fowl, quail, pheasants and ostriches are included in the more than 140 species that are susceptible to avian influenza. AI virus is carried by wild birds, particularly waterfowl and shorebirds, around the world; for the most part without causing any apparent clinical disease. Wild ducks in particular can carry the virus and can then contaminate food and water supplies. Occasionally, when exposure to wild birds occurs, AI can infect domestic birds and spread rapidly. Migratory birds, predominantly shore birds and waders from nearby countries in South East Asia, can pose a risk if they harbour avian influenza infection and then mingle with, and transmit this infection to waterfowl that are nomadic within Australia. These nomadic birds can then mingle with and spread the infection to domestic birds such as poultry. It is not unusual for avian influenza virus to be detected in wild birds in Australia. Avian influenza can also spread by the movement of eggs, birds, people, vehicles and equipment between farms, and by clothing, footwear, aerosols, water, feed, litter, biting insects and vermin. There is currently no effective treatment available for birds once clinical signs of avian influenza appear. Vaccines are available for certain subtypes of the AI virus, which may protect poultry from clinical signs of disease if they subsequently become infected. However, routine vaccination for avian influenza is not permitted in Australia. Pigeons and Avian Influenza. Pigeons are not particularly susceptible to AI. They can however become transiently infected with the virus and transmit the virus during this time. Infected pigeons usually display either mild or no symptoms . Birds with symptoms are usually quiet, fluffed, less active ,have a reduced food intake and show a variety of symptoms associated with respiratory distress including coughing, sneezing and a noisy respiration. Pigeons clear the virus relatively quickly and a long term carrier state does not occur. The significance for pigeon fanciers is that because pigeons can transmit the virus, pigeon movement can be restricted. In the past , both in Australia and overseas, restrictions on pigeons have ranged from totally depopulating lofts in the Restricted Area, through to not allowing the exercise of pigeons in the Controlled Area and prohibiting the release of pigeons in races where they would be expected to fly over quarantined areas. At the time of writing Melbourne fanciers are in stage 4 lockdown and racing is not permitted. Had we been racing, this outbreak would have the potential to cause disruption. For the time being, it is too early to say what will happen in this current outbreak. Decisions will be made depending on how effectively the outbreak can be controlled. As for now, pigeon fanciers should just monitor the situation. Further information can be obtained on the Agriculture Victoria website Baytril. Most pigeon racers will be familiar with the medication Baytril. In some circles it has gained the reputation as a veritable ‘cure all’. Yet, of all the medications available to pigeon racers, this is the one that is most often used inappropriately – usually at the wrong dose and often in the wrong situation. Used in the correct way, however, it can be a very useful medication. So what are the facts? What is Baytril? Baytril is the brand name of an antibiotic called enrofloxacin. It is available in tablet form, as an injection and also an oral syrup. The oral syrup can be given directly to the mouth or dissolved in the drinking water. Enrofloxacin is also sold under other brand names in Australia, notably Enrotril. All brands of enrofloxacin oral syrup in Australia are the same strength. Enrotril and Baytril oral syrups both contain enrofloxacin at a strength of 25mg/ml and therefore from a therapeutic point of view are identical. Enrofloxacin belongs to a group of antibiotics called fluoroquinolones. Another antibiotic in the same group, used more overseas, is ciprofloxacin which is often abbreviated to ‘cipro’ by pigeon fanciers. What do these antibiotics do? Fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as enrofloxacin (for example, Baytril and Enrotril) and ciprofloxacin work principally by interfering with the function of an enzyme called DNA gyrase that is required for bacteria to replicate themselves. If an infectious organism can’t reproduce itself then an infection caused by it resolves. Essentially the organism “dies out”. These antibiotics have excellent activity against Mycoplasma (the principle agent of air sac disease). They are also effective against most of what are called gram negative bacteria, which includes Salmonella (which causes the disease Paratyphoid) and E. Coli. They are, however, less effective against what are called gram positive bacteria (such as Streptococcus). Baytril is therefore a poor first choice of an antibiotic for this type of infection. Fluoroquinolones do have some Chlamydial activity. Chlamydia is the agent that commonly causes ‘eye colds’, dirty ceres and deeper infections of the respiratory tract including the air sacs. Although treating Chlamydia infections with fluoroquinolones may eliminate clinical signs, this group of medications is not as effective at actually clearing these organisms from the pigeon’s body as other antibiotics such as doxycycline. The birds appear to get better but, as the carrier state persists, are much more likely to relapse. Baytril has no action against fungi, viruses, canker or parasites. The correct dose The dose of Baytril in birds is 10–30mg/kg given twice daily. The strength of Baytril and all other oral syrup brands of enrofloxacin in Australia is 25mg/ml. This means the dose for a pigeon is 0.2–0.6ml of the neat syrup per bird twice daily or 5–15ml per litre of water. Years ago, lower doses, adapted from mammal doses, were recommended in birds but were found not to be effective against most infections. Potential problems with using Baytril 1. Treating pigeons with Baytril, even healthy ones, for more than 4 days, almost invariably causes a yeast infection (often called ‘thrush’). There are always low numbers of yeasts in the bowel of pigeons. Their numbers are kept in check by the normal ‘good’ bacteria in the bowel. Baytril kills many of these. With nothing to keep them in check, the yeasts quickly multiply, leading to the development of green and sometimes watery droppings and, potentially, a loss of race form. 2. Treating young growing pigeons with Baytril may permanently deform their joints. Baytril can interfere with cartilage deposition on the surface of young growing joints, leading to permanent deformity. This side effect is dose-dependent and so young pigeons, and in particular nestlings, should only be treated with extreme caution and obviously only when necessary. When treated, they must be dosed accurately. Often other antibiotics are a better choice in this situation. 3. Treating hens that are about to lay with Baytril has been associated with the embryos in the eggs subsequently dying. 4. Treating pigeons with fungal infections with Baytril makes them worse. 5. Treating unwell pigeons with Baytril in the absence of diagnostic work can waste time treating for the wrong problem while disease advances, and can subsequently interfere with test results when testing is done. 6. Treating pigeons with Baytril is not part of a routine pigeon health management program. At various times of the pigeon year, medication is used to prevent or control disease and prepare the birds for racing, etc. Baytril is not used in this way. It has no preventative property but simply kills organisms that are sensitive to it and which are in the pigeon at the time of treatment. If birds are re-exposed to these organisms the day after the treatment stops they will be re-infected. I recently had a fancier tell me that every year, as racing approaches, he gives his race team Baytril 1ml to 1 litre of drinking water for 10 days, and that he considered this ‘essential’ for success. Using this drug in this way would achieve absolutely nothing, apart from perhaps making the fancier feel better in some way. I had another fancier ring me about eight weeks before the start of racing. He explained that he had given his race team, in preparation for racing, a long course of doxycycline and a long course of Sulfa AVS (another antibiotic blend). The purpose of his phone call was to ask if he should now give a long course of Baytril. I found this call rather disappointing, for years well-publicised pre-race programs have been published by vets. If nothing else, it just showed how some fanciers have an unreasonable over-reliance on antibiotics. Despite giving all these antibiotics, the fancier had not treated his birds for the common parasitic diseases, had no testing done on his birds to see, in fact, if any medications were necessary, and it had apparently not occurred to him to contact an avian vet earlier for advice. When to use ‘Baytril’ The first thing to say is that Baytril is a prescription medication that should only be used in the loft after talking to your veterinarian, who should have supplied it to you in an appropriate way. Baytril is an expensive drug. In Australia, a 100ml bottle costs about $80. At the average dose of 10ml/L (25mg/ml) and based on an average water intake of 45ml per pigeon per day, it costs about $40 per day to treat 100 birds. A five day course therefore costs $200. To treat 300 birds would cost $600. Because of the expense some fanciers try to make the drug go further by giving less and therefore deliberately under-dosing. This achieves nothing, is a total waste of money, and encourages the development of resistant bacteria. On a lighter note, most fanciers have long-term relationships with their veterinarian, and it is important to that vet that any supply of medication is used appropriately by the fancier. It is common sense and logical really but Baytril should only be used when an infection sensitive to it is diagnosed and, particularly, if other cheaper antibiotic alternatives are thought likely to be less effective. Usually, if individual birds are infected they are separated and treated individually with the straight syrup given to the mouth. If there is evidence of spreading disease, or more than 10% of a flock is infected, then usually the flock is treated through the drinking water. It is worth repeating that Baytril is not a good first line of treatment for respiratory infections caused by Chlamydia, because although it tends to reduce symptoms (that is, make the birds look better) it is not as effective at actually clearing the organism as other antibiotics such as doxycycline, and also causes ‘collateral damage’ by killing a lot of the ‘good bacteria’. Also only approximately 15% of streptococcal strains (a cause of bacterial infection in pigeons) are sensitive to Baytril and so it is not a good choice for this type of infection. Baytril is, however, widely distributed throughout the body and has good tissue penetrating properties. It is thought to actually achieve higher tissue concentrations than blood concentrations. Because of this property it is a good antibiotic choice for gram negative bacterial infections (in particular Salmonella) and some respiratory infections, in particular those due to Mycoplasma. As always, it is worth taking a bit of your veterinarian’s time to see if an antibiotic is part of the answer in controlling a health problem, and also to see if that antibiotic should be Baytril or not. Ask the Vet 1/Is Turbosole an antibiotic? I have asked three different vet assistants and received three different answers. No, yes, and its somewhere in between. Turbosole is an antibiotic. Antibiotics are drugs that kill bacteria and Turbosole is effective against some types of bacteria . Turbosole has action against many bacteria called gram positive anaerobes and also some bacteria called gram negative anaerobes. In addition though, Turbosole also kills single celled organisms called flagellates such as those that cause canker. Anaerobic bacteria, ie those that grow in the absence of oxygen, are not commonly associated with disease in pigeons and so the drug is usually used to treat flagellate infections. 2/Once a pigeon has had Fat Eye, is it likely to reoccur later in the season or do they appear to have some resistance to it? We diagnosed “Fat Eye”, in conjunction with the University of Melbourne, as a Mycoplasma infection, when the condition was first identified in 2017. Beyond that no further investigative work has been done on this particular Mycoplasma and unfortunately there are no funds available for this. However, having said that Mycoplasmas do tend to behave as a group in a particular way. When a bird becomes infected with Mycoplasma it is infected for life. After initial infection the bird mounts an immune response and the bird clinically recovers. Anti mycoplasmal drugs can be used to help the bird recover but the organism is not cleared from the bird’s system as the birds regain their health. Older birds become long term carriers and can give the organism to younger uninfected birds. These older birds are , however, unlikely to develop symptoms themselves unless they become severely stressed. So, in answer to your question, “fat eye” is unlikely to reoccur in the same season and it is likely that the birds develop resistance to it. It is important to remember that not all birds with a swollen, red eye have “fat eye”. Other conditions can look very similar including a very common disease—Chlamydia. If in doubt a swab can be taken from the eye and PCR tests done to check for both Chlamydia and Mycoplasma. 3/ Should probiotics only be used after antibiotics or is there advantage in giving them routinely? Probiotics can be used beneficially following any situation that is likely to disrupt the normal bowel bacteria. Antibiotic use is one of these situations but bacterial populations are disrupted after any stress. Stress induces a disruption of the normal bowel bacteria and , in fact, the beneficial bacteria are the first ones to be lost with stress. Once these beneficial bacteria are lost from the digestive tract they are replaced by an overgrowth of non-beneficial bacteria. This can result in diarrhoea, loss of performance, decreased appetite and, in the stock loft, inhibited growth and limited weight gain in the youngsters. Probiotics restore the balance between beneficial and non-beneficial bacteria. They are best given as soon as possible after the stress or just before the time of the stress. By doing so, disease or performance problems may be avoided. 4/ When a hen is sitting on eggs, does she automatically begin to produce milk a 20 days after the eggs have been laid, or does it begin when the eggs start chipping regardless of how many days the hen has been sitting? Pigeon milk is produced in response to the release of a hormone called prolactin from, primarily, the pituitary gland ( a small gland at the base of the brain). Prolactin is released in turn, in response to the hen feeling the egg against her “brood patch” and later by feeling the chick move within the egg and starting to pip. In order to produce crop milk the lining of the crop has to significantly modify. This is not something that can happen in a few days. The crop needs prolonged exposure to prolactin to make these changes and produce milk. It usually takes at least 16 days for the crop wall to respond to the prolactin and start releasing its lining cells as crop milk. The hen feeling movement within the egg and the chick starting to pip is insufficient stimulation by itself for the hen to produce milk but it can accelerate the process. So, the simple answer is, if you just put chipping eggs under a hen , she will not produce crop milk . If she has been sitting over 16 days, some crop milk will be there but it will be of lower quality and quantity. It is the combination of sitting and then the stimulation of the hatching chick that combine to produce crop milk. Interestingly pigeons (like some other birds, including budgerigars) have a gland in the crop wall called the Teichman gland. The function of this gland has only recently become more fully understood. When the crop enlarges to produce crop milk, this gland also enlarges. The gland produces immune cells and it is thought that these immune cells move from the Teichman gland into the crop milk, in the process giving freshly hatched chicks some passive immunity directly from their parents. What stimulates the gland is unclear, but suggestions have included the altered hormone status that occurs when pigeons produce crop milk, or the chick itself moving in the egg as it starts to hatch.

5 Comments

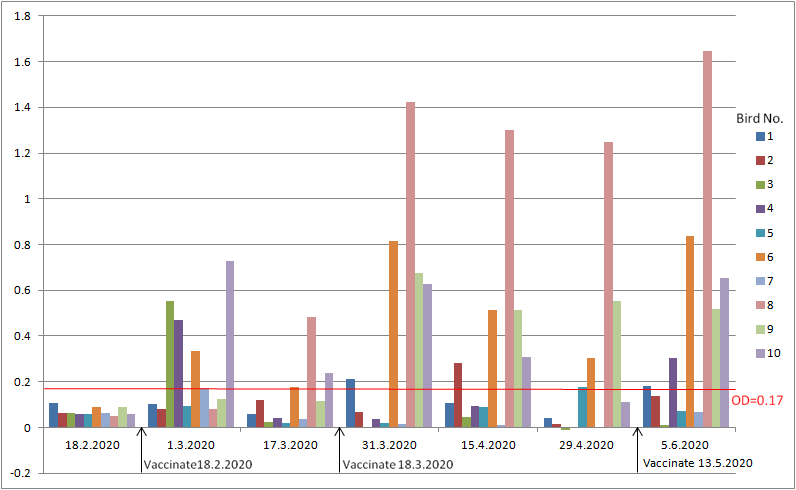

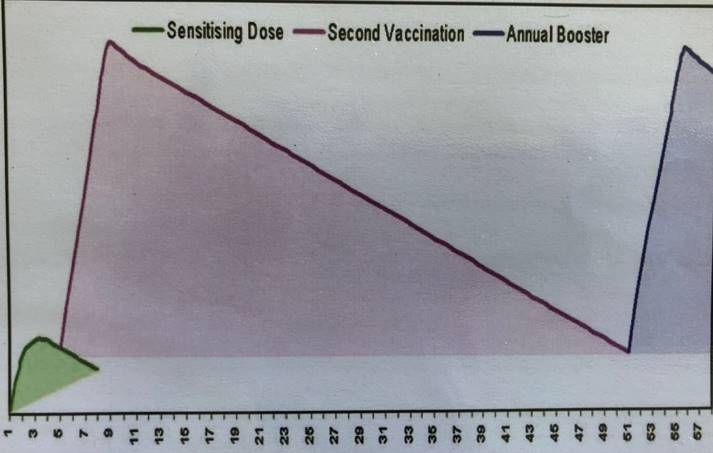

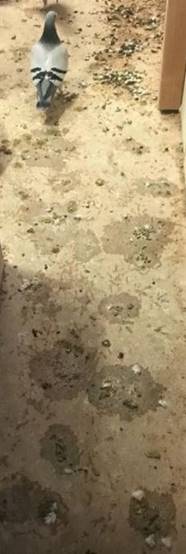

The Rota Vaccine As fanciers would be aware we have been running a pigeon Rota virus vaccine trial for the last 6 months. The results of this trial have been reported in this Journal each month as they have become available. I have prepared a chart below showing the full results of the vaccine trial. The 10 trial birds were bled 7 times. The antibody response is tracked below in each bird. Levels above 0.17 are regarded as protective. The birds were vaccinated on the 18th February and the 18th March. A third vaccination was given on the 13th May. Chart by Dr Colin Walker What can fanciers expect if they have vaccinated their birds against Rota and their birds are subsequently exposed to the virus? Based on the trial results about 60% of birds will have sufficient immunity to stop them from developing clinical disease ie becoming sick. The remaining 40% will have variable levels of immunity but not enough to fully protect them. Any immunity they have, however, will decrease the severity of the disease. Just how sick each of these birds becomes will depend on the level of immunity they have when they are exposed. However, it appears that the vaccine may be more effective than the trial results alone indicate. The trial results are not consistent with what has been happening clinically in many lofts. In the trial we have been measuring the amount of antibodies formed in the blood against Rota virus following vaccination. Even though the test is not straightforward it is the usual test that is done to measure immunity. With many diseases like PMV , measuring antibodies gives a good idea of the likely immune response. At the start of the trial there was discussion as to whether or not this was likely to be the case with Rota virus which is primarily a bowel virus. It was thought that even though measuring antibodies in the blood would be useful that there may be an immune response at the bowel lining that may also modify the progress of disease. One suggestion was that trial birds be killed at the end of the trial, that their bowels be removed , samples of mucous be collected from the bowel lining and the amount of immunoglobulins ( another immune mediator ) be measured. Further ways of evaluating the immune response in the trial birds are still being considered. Either way, whatever the immune response is, it does seem as if more than 60% of birds are protected from clinical disease after vaccination. Throughout June in Melbourne, as fanciers started tossing their birds together, there were outbreaks of vomiting in several lofts. Many fanciers assumed that these outbreaks were due to Rota virus but no testing was done. We were keen to see whether these birds did actually have Rota virus and also if this was the case, did vaccination offer birds some protection from internal damage, particularly to the liver, done by the virus. This can be measured very accurately by drawing blood from the birds and measuring values associated with liver inflammation and function. I was therefore keen to find some droppings from infected birds. Initially a local fancier, who had vaccinated his birds ( two Rotavax 0.5ml 4 weeks apart) rang me and said that about 10 of his 180 birds had started vomiting. Several were quiet and fluffed. I travelled to the loft, collected some dropping and forwarded them to Agribio for a Rota (PCR) test. Two days later while waiting for the results the fancier rang me and said that all of his birds had become well and perhaps it was not worth sending the droppings for testing. The test however had already been initiated and did actually return a positive result. The day after I went to the first loft a second fancier rang me and also said that some of his birds were vomiting. He had about 350 birds and estimated that one in seventy were vomiting. I also travelled to this loft, collected some droppings and forwarded these to Agribio. He had also vaccinated his birds ( two Rotavax 0.3ml 4 weeks apart). Two days later this fancier also rang me. He said that he felt as if he had “cried wolf”. He didn’t think his birds had Rota after all as they had all become well. This test however was also completed and also returned a positive result. A blend of droppings from the first and second loft were used to expose the trial birds to the disease. Despite spending several hours with the birds each day and being a veterinarian I was unable to detect any illness in the trial birds after this exposure. While this was happening, a third fancier contacted me. He had not vaccinated and his birds were now vomiting. I asked him what proportion of his birds were vomiting. He replied, that even though it was not simultaneous, he estimated that over 50% of the birds had vomited. A sample of these droppings were also collected and forwarded to Agribio. They also were positive. Based on this very small sample of only 3 lofts, two vaccinated and one unvaccinated, it does seem as if the benefit of vaccination, as far as reduction of clinical disease in the loft is better than indicated by the trial. We have only tested 3 lofts because the test is expensive and I am paying for them myself. Even though we have only tested 3 lofts other fanciers who have and have not vaccinated and who have experienced outbreaks of vomiting consistent with Rota virus have contacted me and anecdotally it does seem as if the birds that are vaccinated experience a much milder form of the disease if subsequently exposed to Rota virus. The fanciers of vaccinated birds reported that the first sign they noticed was some birds crops not emptying overnight. Vomiting started 3 days after the probable exposure and persisted for 2 to 3 days . In total about 1-5 % of birds vomited . Some droppings became a bit green and wet but overall were not bad. No droppings became watery and mucoid . Birds continued to exercise normally although some were a bit quiet and fluffed. Recovery seemed comparatively rapid. Three days after the vomiting stopped all birds seemed normal. One bird in the first fanciers loft died . All 3 fanciers that we tested have given permission for me to bleed some of their birds. I will do this in about 3 weeks and run complete biochemistry /hematology profiles. The reason for doing this is to compare the amount of internal damage in vaccinated and non- vaccinated birds after a Rota virus exposure. The blood profile that is described in both my book “The Pigeon” on pages 42 and 43 and is also on the APC website in “The Diagnostic Pathway” section will be done. In particular I will be interested to look at the liver parameters. I will also draw blood for the same tests from some of the trial birds. The difference in the results between vaccinated and non- vaccinated birds will be very interesting and will be reported in this magazine next month. The Rota vaccine, although stimulating an antibody level in 60% of birds that is likely to be protective, and appearing to reduce clinical disease is potentially problematic for fanciers because it does not appear to offer full immunity to all birds. A group of 8 fanciers near me toss together. On one Saturday recently one of these fanciers went to basket his birds in the morning for their combined toss. He noticed that several of his birds had vomited overnight and decided against tossing. Another fancier in the unit tossed routinely. He ended up being 40 out overnight and lost 9 out of about 160. The day after the toss his birds started vomiting. Obviously his birds were just one day behind with their Rota infection . With no obvious symptoms when they were basketed the fancier had innocently basketed them for a long toss while they were incubating Rota with unfortunate consequences. Fancier obviously want and will need to have their birds fully protected from clinical disease before racing starts. Is vaccinating against Rota worthwhile? Fanciers are familiar with Pox and PMV vaccines that do confer virtually 100% protection from clinical disease and some may think that all vaccines are similar , however not all vaccines are the same. Making a vaccine is never easy and a number of vaccines do not confer full immunity and also need repeated inoculations. It appears as if this is the case with the current Rota vaccine. I am, however, a firm believer that any immunity is good immunity. It will indeed be frustrating however if fanciers will still need to expose their birds to the virus before racing to fully protect them. It is only natural that the immunity formed by exposure to the whole virus will be higher than that formed by exposure to just part of the virus as in the vaccine. The whole point of vaccination is to develop an immunity safely without damaging the pigeons. It will indeed be interesting to see the results of the upcoming biochemistry/haematology tests. I am interested to hear the experiences of fanciers, who both did and did not vaccinate their birds, after a Rota virus exposure. To some extent what is happening now in Australia is like a giant field experiment or clinical trial. It is the first year that the Rota vaccine has been available to all of us. Such experiences will further help evaluate the vaccines effectiveness. I can be contacted on 0412481239 and [email protected]. I hope fanciers find my efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of the Rota vaccine useful in guiding the decisions they make with their birds. Election of National Body Members In the most recent edition, the July edition, of this magazine, on page 28 was an advert from the ANRPB for the position of Victorian delegate. The advert invited nominations, listed the preferred abilities of an applicant and suggested a resume be sent to the ANRPB assistant secretary. I just wonder what happens next. To me, and I hope that my interpretation is wrong, the advert seemed like an advert for a job in private business and, to me, gave the impression that the Board would then select the successful applicant from any nominations received. I feel that Victorian fanciers must select who represents them. It is not the job of the Board to select Board members but rather fanciers’. Otherwise the Board could simply become a “boys club” where Board members could select members whose views were similar to their own. The election of Board representatives needs to be totally transparent. At the time of writing (July 2020) there is also an advert for the position of Board secretary on the Board website. Here interested persons are invited to contact their state rep and the ad concludes by stating that “All enquiries will be kept strictly confidential”. I can see how such a statement might be added at the end of an advert for a position in private business but am wondering if this is appropriate for a national body for which everything should be totally transparent. I feel that the whole selection of Board members needs to be reviewed. When do Australian fanciers get to elect the national body that represents them? The attitude of most fanciers that I have spoken to, towards the Board and its members, is one of apathy. Most, however, believe that it would be good to have a representative national body. Some are frustrated and even angry about issues regarding the current Board. When asked “What has the Board done? “, most are aware that the Board was involved in some way in the allocation of the Rota vaccine in early 2019. Some are aware also that in the last 1 to 1 ½ years the Board has celebrated the achievement of pigeons in the First and Second World Wars 75 and 100 years ago. Beyond that, I have not spoken to a fancier who is aware of the Board, rightly or wrongly, doing anything else. An important tenet of a national body and indeed a major claim of the current body is that it represents the pigeon fanciers of Australia. However under the current system not all fanciers are being equally represented and some are not being represented at all. Given this situation, it is understandable that many fanciers are apathetic. A big issue currently is the lack of proportional representation. At the moment, the vote of the WA representative carries the same weight as that of the NSW and Victorian representatives (at the moment this position is empty) despite the NSW and Victorian members each representing the interests of 4 to 5 times the number of fanciers. To me, a much fairer system would be to use the delegate system already used by many clubs and federations rather than simply having one rep/one vote per state. In the delegate system, for example, a rep could get one vote for every 50 fanciers he represents. This would mean that WA would get perhaps 2 votes while Victoria and NSW would each get 8 and result in a more accurate representation of fanciers’ wishes. Another problem is that some fanciers are not represented at all. In states like SA, it is potentially easier to choose a state rep. In SA, most fanciers race in Adelaide and Adelaide only has one racing organization. In Victoria, most fanciers are in Melbourne but in Melbourne there are 5 federations. There are also significant numbers of fanciers and clubs associated with some of the larger rural centres. I would suggest that, if the number of fanciers in rural Victoria were combined, t this number would be similar to the total number of fanciers in WA and yet no one represents these Victorian country fliers. They were not involved in the selection of their state rep in any way. No wonder that they might feel uninvolved and uninterested. It appears at the moment as if the Board has 6 members of which 5 can vote, although it can be a bit hard to keep track as various members are joining and then resigning. Since 2017, the Board has contained some very experienced and talented members. Many of these have now left, which I feel is a shame. Speaking to some of them, they said that they left because of disagreements within the Board and a feeling that they were just wasting their time. One difficulty is that the Board is actually a very small group. The difficulty with such a small group is that a non-voter, be it the chair or someone else, can lobby, intentionally or otherwise, the voting members. It is only natural that a non-voter would express his views and that this could influence the vote, particularly of a new less experienced member. This could lead to just a few people, at the moment 5, dictating national policy. I think it is imperative that any national body needs to develop a good understanding of the members that it is meant to represent. A good starting point, I would think, for an Australian national body would be to find out actually how many fanciers there are and where they live. How can a national body claim to represent the interests of its members or know what the broader pigeon community wants if they don’t survey them or allow them to vote on issues? At the moment, to me, it seems that the Board takes a position and then expects the fancy to follow. After speaking to reps that have left the Board, there seems to be a trend to silence people who have different views. I think part of the apathy that most fanciers feel for the Board is a consequence of their lack of confidence in its members. Most were not involved in their selection and they feel not involved and removed from the whole notion of a national body. When do we have elections for a national body? Is it not standard for positions to be declared vacant at the AGM and then the positions filled through election? Are the current Board members there until they choose to leave? When looking to fill positions on the Board, we should not be looking to just put “bums on seats”. If elected by fanciers of a whole state, then election is an endorsement of that person by the state as a reliable representative in whom they have confidence. At the moment, this does not seem to be the case. Maybe we don’t need to have Board elections. Maybe they would be too hard to organize. Maybe a more workable solution would be that part of the position of a senior committee member in a federation or large club, perhaps the secretary or vice president, would be membership of the Board. Because such a representative would be elected and know the local issues, I feel it is likely that fanciers would feel connected, involved and truly represented. Fancy pigeon owners have already had a very effective national body, the Australian National Pigeon Association, for over 25 years and its organization is not that dissimilar to this where the various state reps are often elected to their local organisations or are elected specifically by them as their national representative. Certainly what can be said is that a much more effective and inclusive system, as well as one that is much more transparent, can be developed than the one that is in place now. Use of Doxycycline Doxycycline is a widely used antibiotic in pigeon health management. It is the active ingredient in Doxyvet and one of the active ingredients in Doxy T – 2 products familiar to Australian pigeon fanciers. Doxycycline has poor action against many bacteria in particular Salmonella and E.coli but it is very effective against Mycoplasma and is one of the antibiotics of choice against Chlamydia. Mycoplasma and Chlamydia are commonly involved with respiratory , including air sac infections. Side effects include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhoea, suppression of the immune system, liver damage and alteration of the normal bacteria in the gut. Doxycycline can interfere with calcium metabolism in the gut and in bone and so should be used cautiously in young pigeons particularly for an extended time. Doxycycline does however have many advantages when compared to other tetracyclines such as the “Tricon” and “Aureomycin” that many fanciers will remember. Doxycycline is rapidly absorbed from the bowel, causes less disruption to the normal bowel bacteria, is less affected by concurrent calcium supplementation ( ie less need to remove grit and pink minerals) and provides prolonged therapeutic levels in the blood with a single drink of medicated water providing effective blood levels for up to 20 hours ( compared to about 4 hours for Tricon) . This means that provided a pigeon drinks at least once every 20 hours then the drug is still working. With Tricon the pigeons have to drink every 4 hours including through the night to achieve this (which obviously pigeons do not ). Some aspects of Doxycycline use warrant further comment. Doxycyline medicated water turning purple Fanciers in some areas will notice that water medicated with doxycycline will change from the normal pale yellow to pale pink then red and finally deep purple. This colour change occurs if there are minerals in the water that react with the doxycycline. This change is unlikely to be seen where mains water is used, but is quite common where bore water and other sources of mineral rich waters are used. As the water changes colour the antibiotic is being inactivated. Solutions for fanciers in affected areas include using either bottled water (not mineral water), distilled or rain water. Alternatively, smaller volumes of medicated water can be prepared that are changed more frequently as the pink colour appears. The whole process is accelerated by heat and UV light. In one interesting situation, a fancier observed that the pink colour appeared less rapidly in his white drinkers than in his black drinkers (that absorb heat). Using lighter coloured drinkers placed out of the direct sun will further help in affected areas. Concurrent calcium supplementation Doxycycline absorption from the bowel is reduced if the pigeons ingest supplements that contain calcium, concurrently. To improve uptake of the drug, fanciers should therefore remove grit, pink powder and mineral blocks during medication with doxycycline. Water acidification during doxycycline medication Doxycycline absorption from the bowel can be improved if the doxycycline is provided in a weakly-acidic solution. Simultaneously medicating the water with a weak organic acid;, for example, citric acid or acetic acid, will not only enhance the effect of the drug but also make the somewhat bitter doxycycline more pleasant tasting for the birds. Both citric acid (available as a white powder and dosed at the rate of 3gm/6L) and acetic acid (available as apple cider vinegar and dosed at the rate of 5ml/L) are available from most supermarkets. Doxycycline use and the choice of drinker Drinkers made from galvanised metal or unglazed pottery will inactivate the doxycycline in medicated water. Drinkers should be made from stainless steel, glass, plastic, enameled metal or glazed pottery. Mixing other medications with doxycycline It is sometimes an advantage to treat birds simultaneously with several medications. Doxycycline can be safely mixed with all of the canker medications and also toltrazuril (for coccidia) eg Baycox, Toltravet. It is best, however, not to combine doxycycline with enrofloxacin ("Baytril"), wormers (for example, moxidectin) and multivitamins. Doxycycline should not be mixed with sulphur-based antibiotics as these directly interfere with the effectiveness of the doxycycline. Also if doxycycline is mixed with probiotics then, like other antibiotics,the doxycycline will interfere with the function of the probiotics before they exert their beneficial effect. Giving doxycycline combined with bacteriocidal (ie antibiotics that kill bacteria as opposed to those that just stop bacteria reproducing) antibiotics such as penicillins (for example, amoxycillin) and fluoroquinolones (for example, "Baytril") Doxycycyline is a bacteriostatic antibiotic (eliminates infection by stopping bacteria replicating) while amoxycillin and "Baytril" are bacteriocidal antibiotics (eliminate infection by actually killing the bacteria). Giving bacteriostatic and bacteriocidal antibiotics together does not work well. This is because the bacteriostatic antibiotics stop the bacteria from replicating and it is when the bacteria are replicating that they are vulnerable to the bacteriocidal antibiotics. As an example, most authorities agree that giving doxycycline with "Baytril" reduces the effectiveness of the "Baytril" by 50%. Giving doxycycline with other bacteriostatic antibiotics such as tylosin and spiramycin Like doxycycline, spiramycin and tylosin are both bacteriostatic antibiotics. They do not interfere with the action of each other. In pigeons they are commonly used together when combined infections, such as those that occur with respiratory infections, are suspected. Common brands are DoxyT and TripleVet. Doxycycline compared to other tetracyclines Doxycycline varies from other tetracyclines, such as chlortetracycline and oxytetracycline, in its therapeutic activity, in a number of ways. The three most important ones are : 1. Longer activity in the blood after a single dose – if a pigeon is dosed in the drinking water with doxycycline, each dose persists in the blood and exerts a therapeutic affect for up to 20 hours. Other tetracyclines only provide effective blood levels for about 4 hours. As pigeons rarely drink every 4 hours and certainly don’t drink through the night this means that doxycycline provides more consistent effective levels in the blood which, in turn, means the birds respond to medication and recover more quickly. 2. Disruption of normal bowel bacteria – doxycycline causes less disruption to the normal bowel bacteria than other tetracyclines. 3. Concurrent calcium supplementation – the effect of doxycycline is less affected by concurrent calcium supplementation. 4. Rapidly absorbed from the bowel. Because of these benefits doxycycline is the preferred tetracycline prescribed by many avian vets. Doxycycline compared to enrofloxacin ("Baytril") "Baytril" is used by some fanciers to treat respiratory infection due to Chlamydia. Doxycycline is a more effective treatment. "Baytril" stops the Chlamydia organism replicating itself and leads to a clinical improvement in the birds; that is, they appear to get better, but while treatment with "Baytril" improves the birds, it may not clear the carrier state. Relapses are common. Doxycycline not only stops the Chlamydia organism replicating, but also clears the organism, resulting in a more successful and targeted treatment. Dose of Doxycycline The dose of Doxycycline is 25 -50 mg orally over 24 hours. For Doxyvet this works out to be 3g (one level teaspoon ) to 2 litres of water An Interesting Case. I had a fancier contact me recently . His pigeons looked very well but occasionally developed profuse and watery droppings. Figure 4017 shows his birds droppings as they are normally. Figure 4080 shows the droppings when they are watery. He was sure that a disease was present. The birds did not have diarrhoea. The droppings were watery because they contained a lot of urine. This occurs either when the pigeons are drinking a lot or alternatively when the pigeons are drinking normally but there is a problem with the kidneys causing them to lose the ability to concentrate urine and conserve body fluids . A common cause of pigeons drinking a lot is being given supplements that contain excessive sugar or salt – both of which create a thirst. On questioning we realised that the droppings only became wet after he had used a particular supplement . The product in question is a water soluble vitamin supplement. It has been around since the 1970’s. I was surprised to still find it on the market. On checking I found it is available on line and also through some produce stores. The person selling it the fancier advised that it was really good and he should try it. He used it himself on his birds. Withdrawal of use of the product resolved the problem. Interestingly the seller advised that he was having problems with his own birds droppings but had failed to make the connection. Fanciers need to be extremely cautious about buying over the counter supplements. They are not regulated. A recent survey presented by an avian vet at an avian veterinary conference revealed that only 20% of over the counter bird products actually contained what was listed on the label. You just don’t know what you are getting . Many of them are based on very poor science to begin with being formulated by “backyarders”, literally. Interestingly the fancier whose birds had the watery droppings also reported that his birds were eating rabbit droppings. In fact, they were more than just eating them , they were actively seeking them out and eating every one they could find. This indicated a pica – where pigeon eat large amounts of unusual substances trying to source nutrients that are deficient in the diet. The supplement in question apart from creating a thirst was leaving the pigeons nutritionally stressed. Picas are discussed more fully in the answer to question 7 in the “Vet Questions Answered” section in this magazine. The supplement in question and others like it are still available and there will fanciers in Australia using it today. Fanciers are most definitely advised to use Australian registered products that have been approved by the relevant authorities after passing appropriate manufacturing requirements and standards

Ask the Vet 1/ Will Moxidectin kill air sac mites and the mite that cause problems on the racing pigeons chest? Moxidectin at a dose of 1mg/kg will kill mites ( including air sac mites ) but the bald “moth –eaten” area that you see in the centre of the chest of some pigeons is not due to mites. Many fanciers mistakenly believe that this problem is due to mites. The problem is invariably mechanical damage to the feathers due to them being repeatedly rubbed on the edge of a hopper, drinker or trap. The problem corrects with the moult and will not recur with modifications to the offending device. If there is any doubt a skin biopsy can be collected for microscopic examination. We saw this issue in the clinic also when I worked in Belgium last year. After doing more than 100 skin biopsies we have never identified a mite infection as the cause. 2/ Over the years I have had the tip of the tongue drop off. What would cause this ? Could it be canker ? The only situation that I am aware of where this can have a disease cause is where a mucosal pox vesicle affects the tongue or exposure to some fungal toxins that interfere with peripheral blood supply. It is unlikely to be canker. The tip of the tongue is too exposed for the fragile organisms that cause canker to do this. If it is just the odd bird and they are otherwise well the cause may just be an injury to the tongue. 3/ I feel my pigeons are lacking condition and their wattles are not chalky white but are slightly grey. Do you think this is ornithosis ? Not all grey wattles are a problem. Flying in rain and billing can remove some of the white leaving the cere with a pink or grey colour tone. Grey however does raise the possibility of a sinus infection. If the sinuses are infected discharges drain through the “slot” into the throat and also under the cere. These can soak into the ceres and stain them. At this time of year the usual sign that will alert you to a sinus infection is increased sneezing in the loft. If there is a sinus infection the most likely cause is Chlamydia/ Mycoplasma which is sometimes described as the ornithosis complex. However bacteria, in particular Klebsiella, and some fungi can be involved. Birds on a vitamin A deficient diet are more prone to respiratory infections generally so it is worth checking that there are adequate levels in the diet. If the cause is unclear the usual tests that would be considered are a blood profile ( as set out on pages 42 and 43 of my book The Pigeon ) ,microscopic examination of a crop flush , Mycoplasma and Chlamydial PCRs and collection of a swab for bacterial and fungal testing. 4/ My birds must have a respiratory infection because they pant a lot after a short fly. What should I treat them with ? Fanciers often think this and it is reasonable because panting is a respiratory function. However any disease can sap energy and cause an exercise intolerance. Just as often no disease is present and the birds are either hot, fat , unfit , being forced to fly beyond their fitness capability or are struggling to aerobically release energy to the muscles. Only testing can provide the answer. Tests similar to those in the above answer are used. 5/ My pigeons are “not right”. I was suspicious of a food problem. I tested my sorghum and it went mouldy. How can I fix my birds? Testing grain by seeing if it will go mouldy is not a valid test . The number of fungal spores on a grain is irrelevant. What is relevant is the level of fungal toxin on the grain. The correlation between the number of spores and the level of toxin is very poor. The sorghum may well be fine. If really concerned the grain can be sent to a lab for toxin level estimation. This is a sophisticated test and not something that a veterinarian can do in private practice. This test is also quite expensive . It is important that a fancier’s money is spent wisely. Usually more routine tests are done initially to check for health issues and the toxin level test is only done if these tests fail to identify the cause or suggest that a problem with the food is likely. Once health issues are identified accurately they can be treated in a targeted way. 6/ There is a heap of Adelaide lofts with “Fat eye” right now in addition to many with Rota. What is “Fat eye”? What is the treatment? Can they race with it? Is it contagious? We investigated this problem with the University of Melbourne when it was first reported in 2017. A full range of tests was done including a Mycoplasma PCR from inside the eyelids and a conjunctival biopsy ( where a tiny piece of tissue is taken from the inside of the eyelid for microscope examination ). Tests showed the problem to be a Mycoplasma infection. The infection runs a natural course of about 5 days. If birds are treated with a mycoplasmal drug such as Doxy T they appear to get better a day or two earlier. Some fanciers use eye drops, particularly ones containing an antibiotic called chloramphenicol. Use of eye drops is laborious. Doxycycline given orally ends up in the tears and is likely to be similarly effective. One would expect that the racing of birds would be compromised while affected. The condition is contagious and one would therefore expect it to be spread through racing and toss units. 7/ My pigeons have started pecking at their own droppings and eating some of them. I give them peas and wheat as well as grit. They are handfed but are given as much as they want. What could possibly be wrong? Your pigeons are displaying a behaviour described as Pica. Pica describes a desire to eat either inappropriate material or excessive amounts of a particular substance. Pigeons typically do this when they are trying to source a nutrient that is low in their diet. Some pigeons will eat their own droppings. Stock birds that continually peck at perches or appear to be forever foraging are affected. I have seen pigeons deliberately source and eat cobwebs. In pigeons it is most commonly seen as gorging on grit . Affected birds are usually either on a deficient diet or have a health problem that interferes with the digestion and assimilation of nutrients. Conditions that inflame the bowel wall interfere with nutrient absorption and birds can develop this behaviour even on a complete diet. This means that the birds, even though they eat grit or food offered they cannot get the nutrients these contain and become deficient in vital minerals and other nutrients, often at a time when demand is high, such as breeding. The birds try to compensate for this by just eating more grit. Some fanciers mistakenly remove the grit in this situation, which only compounds matters. If a nutritionally deficient diet is provided, the birds may eat unusual substances in an attempt to source nutrients, or gorge on the provided food trying to compensate for its poor nutritional value Gorging on grit or continuous foraging and ingestion of unusual substances occurs if: 1. the birds are on a deficient or poorly balanced diet 2. the birds are outright hungry 3. the birds have crop or stomach pain 4. a grit-based substrate is novel to them 5. a malabsorption (for example, Salmonella or coccidia) or maldigestion (for example, pancreatic insuffiency) disorder interferes with the assimilation of nutrients. In healthy birds provision of a complete diet usually stops the problem. I usually recommend APC Multiboost in the water for one day per week and APC PVM pink minerals continually available . This usually solves the problem. In your case providing a wider variety of seeds as well as checking that the brand of grit used is good quality one (ie variety of soluble and non -soluble grits presented hygienically (double sieved , washed and dried by the manufacturer)will be beneficial Rota Vaccine Trial