- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

Modern methods

I graduated as a vet in 1979, that’s 34 years ago. At that time, to safely anaesthetise a bird, and see it recover, was regarded as remarkable. To do major surgery and have the bird survive was considered a small miracle. Since that time, there have been quantum leaps in medication, techniques and knowledge available to veterinarians. Anaesthesia and operating on a bird now carry similar risks to that associated with operating on dogs and cats. If a bird does die, it is now unusual and warrants investigation.

It has been said, however, that being anaesthetised, is as close to being dead as you can get, and survive. Birds now routinely survive procedures because of the safe anaesthetics available to vets and due to advances in the techniques associated with surgery generally. Some avian vets regard pigeons as ‘God’s gift to avian vets’ because they are so tough. Pigeons can recover from major injuries, or severe disease, with appropriate care, where some more fragile species may not. They are still, however, living beings which need to be managed correctly. Many fanciers are unaware of what is involved in anaesthesia and surgery.

A surprisingly large number of fanciers still regard it as normal to attempt surgeries such as suturing a cut, or removing a skin tumour, on one of their own conscious pigeons, even though it is known that pigeons have a similar level of pain perception to ourselves. Others will state how valuable or important a bird is to them, but at the same time, refuse to take the bird to a vet, because they feel it is too expensive. Truly ironic! Others are openly critical of vets, after they have taken their pigeon to a general practitioner vet and asked them to do a specialised procedure. If fanciers need specialist avian veterinary work done, they need to see a qualified avian vet. I breed sheep but, despite being a vet, get a sheep vet to attend to them when they are unwell. What steps are available to a veterinarian when operating on a bird? Individual veterinarians use their discretion, depending on the severity of the problem, to decide what is required.

1. Pre-anaesthetic assessment and treatment. Birds are thoroughly examined, and any condition that is likely to compromise recovery is corrected. If birds have been unwell for a period of time, they are often dehydrated, hypoglycaemic (have low blood sugar levels) and hypothermic (have low body temperature). Sick or injured birds often do not eat or drink enough to maintain an adequate level of energy or hydration. If necessary, birds for surgery are admitted to the clinic, and these problems addressed.

Liquid convalescent diets are available, that can be given via a crop tube (the bird equivalent of a stomach tube) into the crop. These are nutrient-rich, easy to digest, and often given warm. Balanced electrolyte solutions (for example, lactated ringers) can be given either subcutaneously (under the skin) or through a catheter placed into a vein or bone cavity. Common veins used are the right jugular (on the right hand side of the neck), the basilic (under the wing) or the medial tarsal (on the inside of the leg).

In many of the long bones in birds (for example, in the wings or legs), entry points are available where catheters can be inserted. The marrow in birds is quite different from that in mammals and appears a bit like raspberry jam. Fluids that are given into the marrow cavity are quickly absorbed into the bird’s circulation and 50ml/kg/day is regarded as normal for maintenance. Most sick birds are 10% dehydrated. Additional fluids are usually given over 48 hours to correct this. Unwell birds are usually held in thermostatically controlled heated cages.

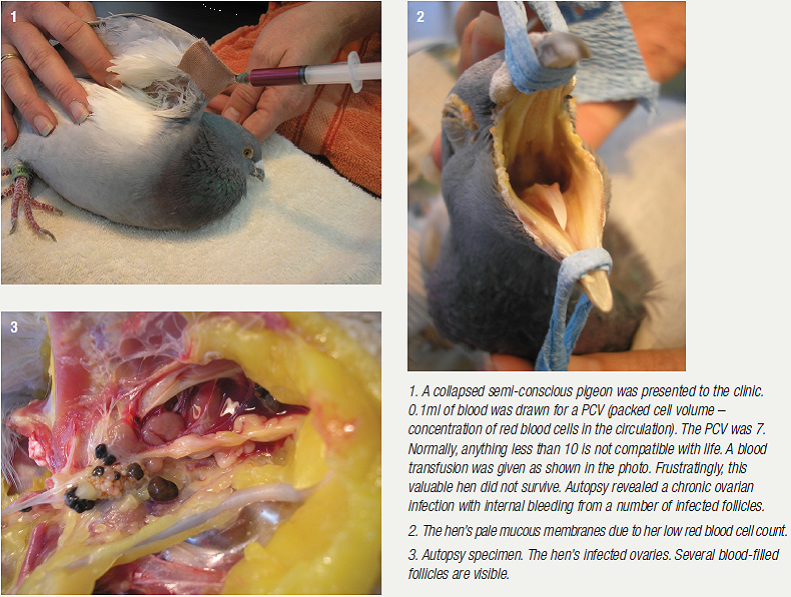

Specific medications for identified problems can also be given. The result is a warm, hydrated bird in a positive energy balance, which is a much better surgical candidate. Offering this supportive care dramatically improves the bird’s chances of handling anaesthesia and a surgical procedure well. If necessary, blood can be drawn for testing. As a bare minimum, a PCV (concentration of red blood cells) and TP (total protein) will provide an insight into the level of debility. If necessary, more thorough tests covering biochemistry (organ function tests) and haematology (red and white blood cell parameters) can be done. In city practices, these results are often available within four hours.

I graduated as a vet in 1979, that’s 34 years ago. At that time, to safely anaesthetise a bird, and see it recover, was regarded as remarkable. To do major surgery and have the bird survive was considered a small miracle. Since that time, there have been quantum leaps in medication, techniques and knowledge available to veterinarians. Anaesthesia and operating on a bird now carry similar risks to that associated with operating on dogs and cats. If a bird does die, it is now unusual and warrants investigation.

It has been said, however, that being anaesthetised, is as close to being dead as you can get, and survive. Birds now routinely survive procedures because of the safe anaesthetics available to vets and due to advances in the techniques associated with surgery generally. Some avian vets regard pigeons as ‘God’s gift to avian vets’ because they are so tough. Pigeons can recover from major injuries, or severe disease, with appropriate care, where some more fragile species may not. They are still, however, living beings which need to be managed correctly. Many fanciers are unaware of what is involved in anaesthesia and surgery.

A surprisingly large number of fanciers still regard it as normal to attempt surgeries such as suturing a cut, or removing a skin tumour, on one of their own conscious pigeons, even though it is known that pigeons have a similar level of pain perception to ourselves. Others will state how valuable or important a bird is to them, but at the same time, refuse to take the bird to a vet, because they feel it is too expensive. Truly ironic! Others are openly critical of vets, after they have taken their pigeon to a general practitioner vet and asked them to do a specialised procedure. If fanciers need specialist avian veterinary work done, they need to see a qualified avian vet. I breed sheep but, despite being a vet, get a sheep vet to attend to them when they are unwell. What steps are available to a veterinarian when operating on a bird? Individual veterinarians use their discretion, depending on the severity of the problem, to decide what is required.

1. Pre-anaesthetic assessment and treatment. Birds are thoroughly examined, and any condition that is likely to compromise recovery is corrected. If birds have been unwell for a period of time, they are often dehydrated, hypoglycaemic (have low blood sugar levels) and hypothermic (have low body temperature). Sick or injured birds often do not eat or drink enough to maintain an adequate level of energy or hydration. If necessary, birds for surgery are admitted to the clinic, and these problems addressed.

Liquid convalescent diets are available, that can be given via a crop tube (the bird equivalent of a stomach tube) into the crop. These are nutrient-rich, easy to digest, and often given warm. Balanced electrolyte solutions (for example, lactated ringers) can be given either subcutaneously (under the skin) or through a catheter placed into a vein or bone cavity. Common veins used are the right jugular (on the right hand side of the neck), the basilic (under the wing) or the medial tarsal (on the inside of the leg).

In many of the long bones in birds (for example, in the wings or legs), entry points are available where catheters can be inserted. The marrow in birds is quite different from that in mammals and appears a bit like raspberry jam. Fluids that are given into the marrow cavity are quickly absorbed into the bird’s circulation and 50ml/kg/day is regarded as normal for maintenance. Most sick birds are 10% dehydrated. Additional fluids are usually given over 48 hours to correct this. Unwell birds are usually held in thermostatically controlled heated cages.

Specific medications for identified problems can also be given. The result is a warm, hydrated bird in a positive energy balance, which is a much better surgical candidate. Offering this supportive care dramatically improves the bird’s chances of handling anaesthesia and a surgical procedure well. If necessary, blood can be drawn for testing. As a bare minimum, a PCV (concentration of red blood cells) and TP (total protein) will provide an insight into the level of debility. If necessary, more thorough tests covering biochemistry (organ function tests) and haematology (red and white blood cell parameters) can be done. In city practices, these results are often available within four hours.

2. Pre-anaesthetic medication. 5–10 minutess before induction of anaesthesia, medications that control pain can be given. This means less anaesthetic needs to be given through the procedure, the level of anaesthesia is more stable, and the animal is more likely to recover smoothly, and resume eating and drinking sooner.

3. Anaesthetic induction. A face mask is placed over the bird’s beak and pure oxygen allowed to flow. This oxygenates the bird’s blood. After about 30 seconds, anaesthetic gas is introduced, and the bird then loses consciousness, usually within one minute. Pigeons are vertebrates like us and have a similar level of pain perception. The idea of operating on a conscious pigeon, entertained by some fanciers, is incredibly cruel. A pigeon becoming quiet in this situation is simply its way of dealing with pain.

4. Anaesthetic maintenance:

a. Once the bird is anaesthetised, a tube called an endotracheal tube can be inserted into the windpipe. This can be either directly connected to the anaesthetic machine or to an intermittent positive pressure ventilator (IPPV machine). IPPV machines monitor the bird’s breathing and will breathe for the bird if necessary. Birds do not have a diaphragm (as a mammal has) and have to breathe with their chest wall. Old or debilitated birds can quickly tire when anaesthetised and may not be able to breathe sufficiently to survive.

b. Anaesthetic depth can be monitored in a number of ways. Often, the simplest way is to monitor the respiratory rate and depth and also response to painful stimuli. Pulse oximeters measure pulse and heart rate, dopplers measure pulse and blood pressure. The bird can be connected to an echocardiogram (ECG) to monitor heart function and identify any arrhythmias. A capnograph, which measures carbon dioxide levels in expired air, can be connected to the airway. Being able to monitor the depth of anaesthesia accurately, means the bird can be kept as light as possible; that is, given the least amount of anaesthetic necessary, without regaining consciousness.

c. It is a standard practice in involved surgical procedures to insert a 24G catheter into a vein and connect this to an intravenous drip or, more often, an infusion pump. These are usually set to deliver 10ml/kg/hr so that the bird can maintain a normal peripheral blood pressure during surgery. If necessary, a blood transfusion can be given. This may sound involved, but is remarkably routine. There is no need to type avian blood, as a reaction can only potentially occur if a second transfusion of the same blood type is given. It is unusual for a pigeon to require a second blood transfusion, and even if this is given, the many different blood types in birds make the chance of a reaction occurring very small. Blood can be drawn from a pigeon donor into a heparinised (anti- clotting) syringe and the blood run through a catheter with an on-line micro sieve, directly into the 24G catheter in the surgical bird.

3. Anaesthetic induction. A face mask is placed over the bird’s beak and pure oxygen allowed to flow. This oxygenates the bird’s blood. After about 30 seconds, anaesthetic gas is introduced, and the bird then loses consciousness, usually within one minute. Pigeons are vertebrates like us and have a similar level of pain perception. The idea of operating on a conscious pigeon, entertained by some fanciers, is incredibly cruel. A pigeon becoming quiet in this situation is simply its way of dealing with pain.

4. Anaesthetic maintenance:

a. Once the bird is anaesthetised, a tube called an endotracheal tube can be inserted into the windpipe. This can be either directly connected to the anaesthetic machine or to an intermittent positive pressure ventilator (IPPV machine). IPPV machines monitor the bird’s breathing and will breathe for the bird if necessary. Birds do not have a diaphragm (as a mammal has) and have to breathe with their chest wall. Old or debilitated birds can quickly tire when anaesthetised and may not be able to breathe sufficiently to survive.

b. Anaesthetic depth can be monitored in a number of ways. Often, the simplest way is to monitor the respiratory rate and depth and also response to painful stimuli. Pulse oximeters measure pulse and heart rate, dopplers measure pulse and blood pressure. The bird can be connected to an echocardiogram (ECG) to monitor heart function and identify any arrhythmias. A capnograph, which measures carbon dioxide levels in expired air, can be connected to the airway. Being able to monitor the depth of anaesthesia accurately, means the bird can be kept as light as possible; that is, given the least amount of anaesthetic necessary, without regaining consciousness.

c. It is a standard practice in involved surgical procedures to insert a 24G catheter into a vein and connect this to an intravenous drip or, more often, an infusion pump. These are usually set to deliver 10ml/kg/hr so that the bird can maintain a normal peripheral blood pressure during surgery. If necessary, a blood transfusion can be given. This may sound involved, but is remarkably routine. There is no need to type avian blood, as a reaction can only potentially occur if a second transfusion of the same blood type is given. It is unusual for a pigeon to require a second blood transfusion, and even if this is given, the many different blood types in birds make the chance of a reaction occurring very small. Blood can be drawn from a pigeon donor into a heparinised (anti- clotting) syringe and the blood run through a catheter with an on-line micro sieve, directly into the 24G catheter in the surgical bird.

d. Anaesthetised birds are actively warmed either by placing them on a heat pad or by a radiant heat lamp. A bird’s core temperature always drops through surgery for a variety of reasons; they are still, they may lose blood, internal organs that radiate heat are exposed, feathers are plucked exposing skin, etc. Chilling compromises recovery.

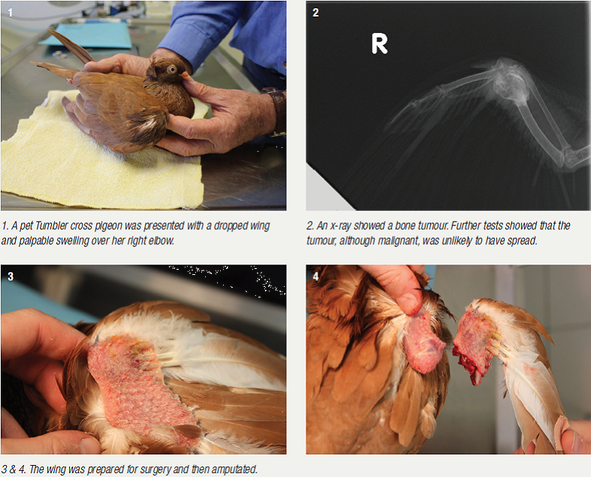

5. Surgery commences. Feathers are removed (but as few as possible) from the incision site. The skin is washed in a non-alcoholic (not evaporative and therefore cooling) disinfectant, usually chlorhexidine and the site is draped. Avian drapes are usually sterile clear sheets of polymer that adhere closely to the skin. Incisions are made through this into the bird, enabling sterile access to the internal structures.

5. Surgery commences. Feathers are removed (but as few as possible) from the incision site. The skin is washed in a non-alcoholic (not evaporative and therefore cooling) disinfectant, usually chlorhexidine and the site is draped. Avian drapes are usually sterile clear sheets of polymer that adhere closely to the skin. Incisions are made through this into the bird, enabling sterile access to the internal structures.

6. Surgery technique. Blood loss is minimised through good surgical technique. Bleeding can be controlled through micro-cautery. Large blood vessels are clamped with tiny metal vascular clips released from an applicator. Many avian surgeons operate either using an operating microscope or wearing magnifying loupes. Small instruments are used. Experienced surgeon/nurse teams that work well together reduce surgery time and increase efficiency. At surgery’s end, fine absorbable non-irritant sutures, not much thicker than a human hair, are used to close the skin.

7. Surgery end. The anaesthetic gas is turned off and the bird is allowed to breathe pure oxygen for about one minute. The endotracheal tube is removed as the bird regains consciousness. An intramuscular injection of an anti-inflammatory pain killing drug is given. The bird is placed in a heated cage to aid recovery under supervision. Food is offered as soon as possible.

8. Convalescence. Post-surgical birds are usually held in hospital for 1–4 days to monitor recovery. Antibiotics, specific medication and pain killers are provided as indicated. Birds that are slow to eat are crop fed a liquid convalescent diet via crop tube. Once the bird has recovered sufficiently to look after itself in the home loft, it is discharged.

7. Surgery end. The anaesthetic gas is turned off and the bird is allowed to breathe pure oxygen for about one minute. The endotracheal tube is removed as the bird regains consciousness. An intramuscular injection of an anti-inflammatory pain killing drug is given. The bird is placed in a heated cage to aid recovery under supervision. Food is offered as soon as possible.

8. Convalescence. Post-surgical birds are usually held in hospital for 1–4 days to monitor recovery. Antibiotics, specific medication and pain killers are provided as indicated. Birds that are slow to eat are crop fed a liquid convalescent diet via crop tube. Once the bird has recovered sufficiently to look after itself in the home loft, it is discharged.

|

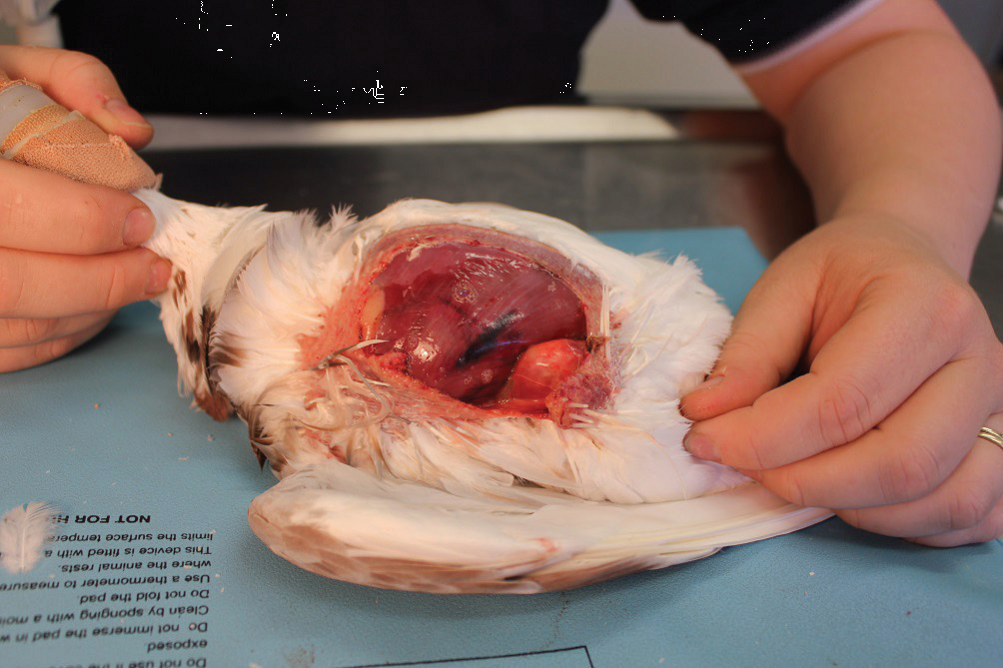

As every fancier knows, pigeons are extremely tough birds. Some vets regard them as ‘God’s gift to avian veterinarians’. They can certainly tolerate severe injury. This feral pigeon was presented after being caught by a member of the public. Its right leg had been torn off and two centimeters of air-dried bone (the tibiotarsus) was exposed. The bird had managed to survive and an attempt at healing had commenced. There was no sign of infection. Under anaesthetic, the exposed bone was removed and a pain-free stump was created. One-legged pigeons cope well because the pigeon learns to centre its weight and the surviving leg increases in strength. |

|

Two fibrolipoma tumours located either side of the vent. These benign fat-based tumours sometimes occur spontaneously, but are more likely to develop in birds on a high fat diet. Such birds often have other problems associated with a diet high in fat, such as fatty liver and high blood cholesterol, leading to cardiovascular disease. Often blood tests are done to evaluate whether these birds are safe surgical candidates. If they are, surgical removal of these tumours tends to be routine. Sometimes, however, changing the affected bird to a diet that is lower in fat and more balanced will cause a reduction in tumour size and make surgery unnecessary. If left, some of these tumours become so large that their physical bulk can interfere with bird movement. Their surface can also become damaged and ulcerated, leading to infection and bleeding.

A 13-year-old racing pigeon with two fibrolipomas, one of which is ulcerated. At this stage the tumours will need to be surgically removed; however, in experienced hands removal should be routine and the bird should make an uneventful recovery. A Coburg Lark was presented with a chronically watery eye. At surgery a large conjunctival cyst was removed. Here the bird is recovering at the end of surgery. |

|

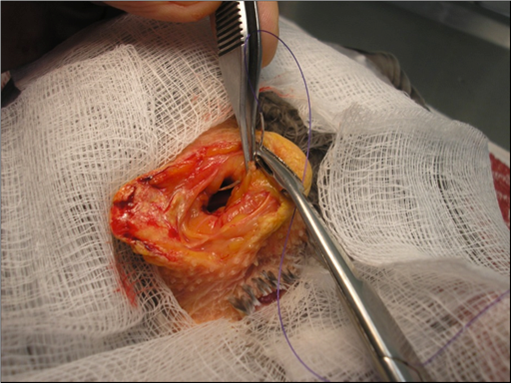

Anaesthetised Blue check pied cock with a large uropygial tumour.

Cancers of the uropygial or preen gland occur occasionally. The type of cancer is determined by microscopic examination of a biopsy (tissue sample collected from the mass). The most common type of cancer in the preen gland is one called a squamous cell carcinoma. These malignant tumours are slow to metastasise (spread into the body) but are very invasive. Treatment involves surgical excision of the tumour as well as a wide zone of visibly normal tissue around the tumour. Results are improved if radiation treatment is given to the surgical site after excision. Radiation therapy is expensive, and the owner of this bird opted for surgical excision only. The tumour did regrow but the bird regained its health for about one year and was able to be bred from during this time. The bird at the end of surgery. |

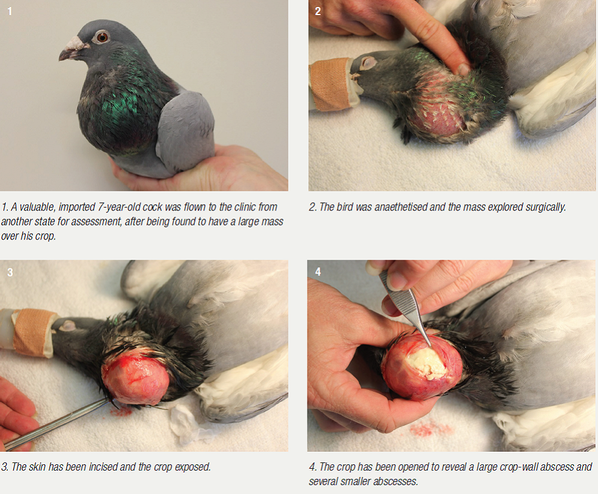

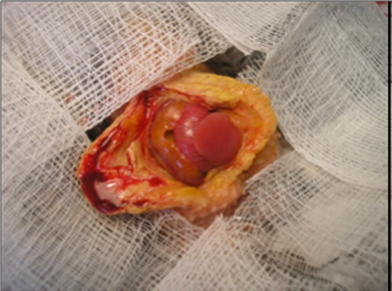

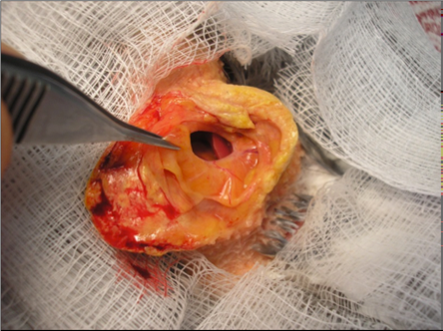

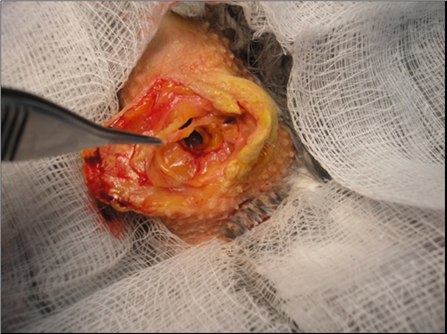

An 8 year old imported Belgium racing hen which had bred many winners was presented with a localised swelling on the ventral midline. The bird was anaesthetised and the swelling surgically opened. The swelling was a hernia containing several loops of bowel and the pancreas. Surgical repair was routine and this valuable hen made a good recovery.

The swelling is opened revealing herniated abdominal content.