- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

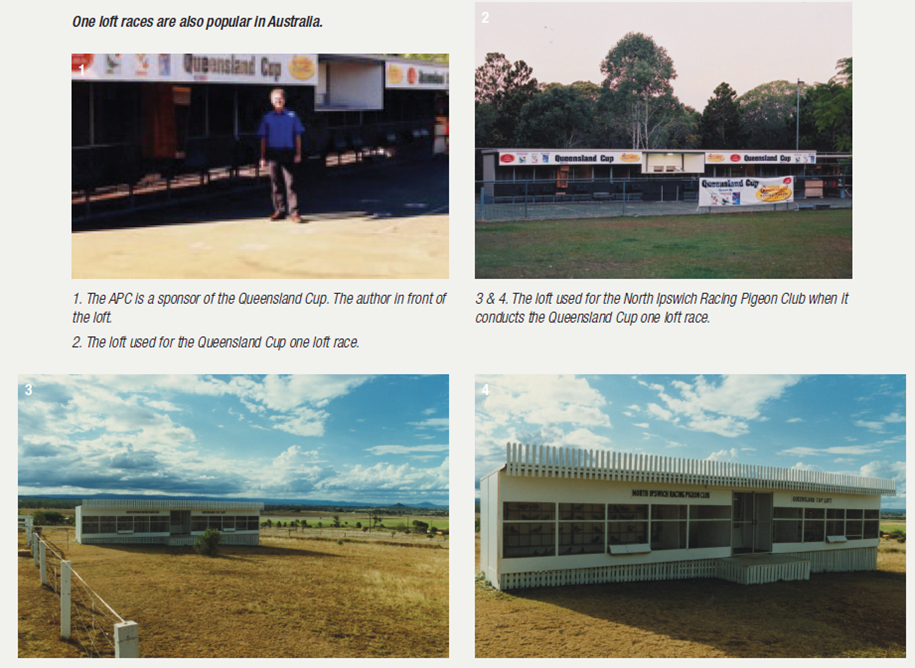

The manager of a one loft race faces many challenges. Some of these are the control of disease and the maintenance of health. Introduced birds can bring with them any disease agent that is present in their home loft. The stress of transport, establishing themselves in the new loft, and their immaturity all increase the newly arrived pigeons’ vulnerability to disease. In one loft races birds come from many different lofts to compete.

The level of care and health management in these lofts will vary. Some birds will arrive in very healthy condition, others may come from lofts where the birds are not even wormed, while still others may come from lofts where herpes virus or paratyphoid are present. All pigeons that arrive for entry into a one loft race are young. Some have travelled a considerable distance and may not have been fed or watered for 24 hours. In some one loft races the birds, upon arrival, are simply put in a loft with the other birds that have already arrived. Common sense tells us that the combination of large numbers of young stressed pigeons, together with a potentially high exposure to disease, can be disastrous.

Holding loft

Ideally, a second small holding loft should be located on the same property but at a distance from the one loft race loft. This can be used to hold the newly arrived babies while they are put through several basic health steps before entering the main loft. Completion of the necessary health protocols should only take two to three days.

As birds arrive, managers are obviously keen to get the birds settled into the race loft as soon as possible. As the birds are going to race to this loft, they need to bond to it and be homed before they get too old. However, the advantages of putting the young ones through a health protocol on arrival is far outweighed by the disadvantages of moving birds into the race loft only a few days later, particularly when looking at the long-term success of the event.

The relevant diseases are internal and external parasites, coccidiosis, paratyphoid, Chlamydia/Mycoplasma respiratory infection, Circo virus, pox virus, Adeno virus, Herpes virus and PMV. It is not possible to prevent all diseases from entering, but it is possible to prevent most, and management programs can be put in place to minimise the impact of the others. Birds should not simply be treated on arrival and placed in the race loft. The young ones, on arrival, are likely to be stressed and therefore react poorly to any treatment

or vaccines given, and also because the treatments take several days to work.

Upon arrival the birds should be placed in the holding loft, which should have been cleaned and prepared for them. For the first 12–24 hours they should be allowed to rest. During this time loft managers need to check that all of them are eating and drinking. Prior to going into the holding loft all birds should be thoroughly examined. Any that are found to be unwell or found to have abnormalities such as multiple ‘fret’ marks should be separated and their owners contacted. Loft managers should be allowed to refuse entry to suspect birds. Once entries are settled in the holding loft, the following routine disease preventative steps can be undertaken:

1. Vaccinations

a. PMV vaccination – in Australia a killed oil based La Sota vaccine is used. Immunity starts to develop in 2 days. 80% of birds will be immune in 4 weeks. A second vaccination needs to be given 4–8 weeks later for 100% of birds to be immune.

b. Pox vaccination – in Australia a modified live vaccine is used; a single inoculation confers long-term immunity.

c. Paratyphoid vaccination – not available in Australia, but should be used in countries where it is available.

2. Parasite control

a. Worms – many effective wormers are available throughout the world. In Australia the normal one used is moxidectin 2mg/ml, 0.25ml/bird, directly into the throat. If tapeworms are a concern consider using moxidectin combined with praziquantel; e.g., Moxidectin Plus, 0.5ml/bird, directly into the throat.

b. Coccidiosis – toltrazuril or diclazuril; giving a single (high) bolus dose is a safe and effective way of eliminating these parasites with a single dose. Toltrazuril 25mg/ml, 0.5ml/bird, directly into the throat.

c. Lice and mites – spray all birds with a bird-safe insecticide; e.g., permethrin. Permethrin 40mg/ml. Dilute 10–20ml per litre and spray each bird across the back, down the chest and, after opening each wing, on the top and below each wing.

3. Canker

Water-based medication needs to be given for at least more than three days to stand any chance of eradicating most trichomonad strains. Tablets are a more effective option. Consider using either Spartrix (carnidazole 10mg) or Ronsec (ronidazole/secnidazole). Give one tablet, wait 48 hours, and give a second tablet. Clinical data states that this will kill greater than 95% of Trichomonads including some hyper-resistant strains.

The level of care and health management in these lofts will vary. Some birds will arrive in very healthy condition, others may come from lofts where the birds are not even wormed, while still others may come from lofts where herpes virus or paratyphoid are present. All pigeons that arrive for entry into a one loft race are young. Some have travelled a considerable distance and may not have been fed or watered for 24 hours. In some one loft races the birds, upon arrival, are simply put in a loft with the other birds that have already arrived. Common sense tells us that the combination of large numbers of young stressed pigeons, together with a potentially high exposure to disease, can be disastrous.

Holding loft

Ideally, a second small holding loft should be located on the same property but at a distance from the one loft race loft. This can be used to hold the newly arrived babies while they are put through several basic health steps before entering the main loft. Completion of the necessary health protocols should only take two to three days.

As birds arrive, managers are obviously keen to get the birds settled into the race loft as soon as possible. As the birds are going to race to this loft, they need to bond to it and be homed before they get too old. However, the advantages of putting the young ones through a health protocol on arrival is far outweighed by the disadvantages of moving birds into the race loft only a few days later, particularly when looking at the long-term success of the event.

The relevant diseases are internal and external parasites, coccidiosis, paratyphoid, Chlamydia/Mycoplasma respiratory infection, Circo virus, pox virus, Adeno virus, Herpes virus and PMV. It is not possible to prevent all diseases from entering, but it is possible to prevent most, and management programs can be put in place to minimise the impact of the others. Birds should not simply be treated on arrival and placed in the race loft. The young ones, on arrival, are likely to be stressed and therefore react poorly to any treatment

or vaccines given, and also because the treatments take several days to work.

Upon arrival the birds should be placed in the holding loft, which should have been cleaned and prepared for them. For the first 12–24 hours they should be allowed to rest. During this time loft managers need to check that all of them are eating and drinking. Prior to going into the holding loft all birds should be thoroughly examined. Any that are found to be unwell or found to have abnormalities such as multiple ‘fret’ marks should be separated and their owners contacted. Loft managers should be allowed to refuse entry to suspect birds. Once entries are settled in the holding loft, the following routine disease preventative steps can be undertaken:

1. Vaccinations

a. PMV vaccination – in Australia a killed oil based La Sota vaccine is used. Immunity starts to develop in 2 days. 80% of birds will be immune in 4 weeks. A second vaccination needs to be given 4–8 weeks later for 100% of birds to be immune.

b. Pox vaccination – in Australia a modified live vaccine is used; a single inoculation confers long-term immunity.

c. Paratyphoid vaccination – not available in Australia, but should be used in countries where it is available.

2. Parasite control

a. Worms – many effective wormers are available throughout the world. In Australia the normal one used is moxidectin 2mg/ml, 0.25ml/bird, directly into the throat. If tapeworms are a concern consider using moxidectin combined with praziquantel; e.g., Moxidectin Plus, 0.5ml/bird, directly into the throat.

b. Coccidiosis – toltrazuril or diclazuril; giving a single (high) bolus dose is a safe and effective way of eliminating these parasites with a single dose. Toltrazuril 25mg/ml, 0.5ml/bird, directly into the throat.

c. Lice and mites – spray all birds with a bird-safe insecticide; e.g., permethrin. Permethrin 40mg/ml. Dilute 10–20ml per litre and spray each bird across the back, down the chest and, after opening each wing, on the top and below each wing.

3. Canker

Water-based medication needs to be given for at least more than three days to stand any chance of eradicating most trichomonad strains. Tablets are a more effective option. Consider using either Spartrix (carnidazole 10mg) or Ronsec (ronidazole/secnidazole). Give one tablet, wait 48 hours, and give a second tablet. Clinical data states that this will kill greater than 95% of Trichomonads including some hyper-resistant strains.

All of the above are basic preventative measures that will do the youngsters no harm. In addition, some managers may wish to screen the incoming birds for Adeno virus and Circo virus. These tests are too expensive to be done on individual birds, but batches of babies can be screened as they arrive. For Adeno virus a QUICK test can be done on a pooled dropping sample. Fresh droppings should be gathered throughout the holding loft or the basket that the birds arrived in.

These are tested by following the simple instructions that come with the QUICK test. Results are available in under ten minutes. The test costs AUD$10–40, depending on where you are in the world. The test for Circo virus requires a drop of blood to be taken from several of the birds. This sounds tricky but it is not. The end of the toe is washed with some warm water on a tissue, a 27G needle is used to prick the skin, a drop of blood oozes on to the surface. This is wiped on to the supplied test paper. Blood from several birds

can be wiped on to the same paper and then submitted to the vet as a pooled sample.

Frustratingly this test takes five to ten days to be available (depending on where you are in the world) which means the results are not available until the birds are already in the race loft. Managers may, however, decide testing for this is worthwhile, depending on the prevalence and associated risk of the disease in their area.

On the third day the birds can be moved across into the main loft and their training commences. The holding loft should be disinfected before the next batch of youngsters is introduced with an effective disinfectant designed for this use; for example, Virkon F10. Mixing young babies with older squeakers in the one loft event loft is not ideal. The older youngsters will dominate the younger birds. It is better if the younger birds can be trained and fed separately for two to three weeks before being allowed to mix with the main group of more established youngsters. This two-to-three-week period gives the further opportunity for other undetected

health problems to appear. If they do appear, they will be confined to this batch, making control easier.

Unfortunately Herpes virus and Paratyphoid (due to Salmonella infection) can slip through undetected with this protocol. There are no foolproof live-bird diagnostic tests that will pick up these problems in birds that appear well. However once all the birds for the race have arrived and are settled and eating properly (for about one month) then in countries where a Paratyphoid vaccine is not available, a ten-day course of trimethoprim/sulphadiazine (for example, Sulpha AVS, 3g/4L) can be given. This is unlikely to eliminate Salmonella bacteria from every bird, but it is as much as can be practically done to decrease the chance of this infection leading to disease, and will do the birds no harm. At the completion of this course the birds are older and, with ongoing good care, particularly the avoidance of overcrowding, the maintenance of dry hygienic conditions, and the provision of a nutritious diet the disease is unlikely to cause problems.

In the following months as the birds mature, through to the day of the race, it is respiratory infection due to Chlamydia and Mycoplasma that is most likely to cause health problems.

Pigeons, once they are infected with Mycoplasma, are infected for life. If the birds get stressed then Mycoplasma can cause disease. When antibiotics are given they only restore health, they do not eradicate the Mycoplasma. The Mycoplasma then lies dormant until the birds again become ‘run down’. As the birds get older and develop their immunity it takes more stress to cause disease flare-ups.

Chlamydia will cycle through the growing babies. Text books tell us that if an individual pigeon is given doxycycline (the antibiotic of choice for Chlamydia) for 45 days, it has a 98% chance of actually clearing Chlamydia. If Chlamydia is cleared, then any immunity the pigeon has formed quickly fades and, in fact, has completely gone by six months thus leaving the bird vulnerable to re-infection. If a 45-day treatment could guarantee eradication of Chlamydia it may be worth considering.

However, this is unlikely to occur, and such a long course can compromise the moult and predispose the babies to other health problems such as bowel disease and interference with calcium metabolism. Also, it is worth considering that the birds are likely to be exposed to chlamydia on return to their home lofts after the event, and would be very vulnerable to infection because of their lowered immunity. In a one loft race a better approach is to allow exposure to Chlamydia. In the majority of birds it will not cause disease and, if the birds are being well cared for, will stimulate the development of immunity in them.

If Chlamydia does cause disease, the symptoms to look for are ‘eye colds’ and dirty ceres. If individual birds develop symptoms, these should be treated individually with doxycycline. Leave these birds in the loft and treat them each with doxycycline (for example, Doxyvet) 25mg/bird half a 50mg tablet once daily.

If more than 5–10% of birds are affected, give a flock treatment of doxycycline water-soluble powder (for example, Doxyvet 12%, 3g/2L) for four to seven days. If, however, this number of youngsters are affected, it indicates that something about the loft is interfering with the development of the birds’ immunity. The loft design and management should be reviewed for problems.

Diet

The growing babies should be offered a grain blend with approximately 15-20% protein, 5–7% fat and approximately 2950Kcal/kg of energy. As the moult is completed and the birds spend longer on the wing, the protein can be reduced to 12–14% and the energy increased to 3000Kcal/kg or higher, depending on the birds’ workload. Regular probiotics and a complete multivitamin and amino acid supplement given one day per week will help promote health.

As the day of the race approaches, race managers should consider having several of the birds checked by an avian veterinarian to make sure that there are no hidden health problems. It is better to do this and treat any health problems that are identified, rather than have a bad race and look for the cause later. Race managers should be discouraged from making totally independent decisions about health and treatment. Most race managers are experienced racing fanciers. They would not be in charge of a one loft race if they were not. However, not availing themselves of veterinary assistance leaves the race open to criticism if health problems occur.

One loft race managers should develop a working relationship with their local avian vet. Despite the best of care, simply because lots of birds from lots of different backgrounds are coming together in a single loft for nearly a year, the potential for health issues to arise is considerable. Most avian vets are keen to help with these events and many donate their services free as a service to the sport.

After the race

Fanciers are sometimes concerned that birds coming back to their loft after a one loft race may introduce disease into their own loft. In a well conducted one loft race with health management programs in place, this is unlikely. In a loft without health management programs the risk is significant. In particular, Paratyphoid and Herpes virus are a concern. In the end, fanciers will need to make the final decision here, based on each bird’s potential breeding value and their opinion of how the race has been conducted.

One loft races are great events that bring the pigeon community together. They allow the comparison, through direct competition, of birds from different areas and indeed different countries. They often generate a financial return that can be used to promote the sport, and also for other purposes. In many countries profits from one loft races are donated to charity. In America some fund educational scholarships to provide an opportunity for underprivileged youth. It is great to think that pigeon racing provides an education for some young people. One loft races with big entries and significant prize money have a ‘wow’ factor that helps advertise the sport in a positive way, and indeed draws the sport to many people’s attention. It is therefore important that they are conducted correctly.

These are tested by following the simple instructions that come with the QUICK test. Results are available in under ten minutes. The test costs AUD$10–40, depending on where you are in the world. The test for Circo virus requires a drop of blood to be taken from several of the birds. This sounds tricky but it is not. The end of the toe is washed with some warm water on a tissue, a 27G needle is used to prick the skin, a drop of blood oozes on to the surface. This is wiped on to the supplied test paper. Blood from several birds

can be wiped on to the same paper and then submitted to the vet as a pooled sample.

Frustratingly this test takes five to ten days to be available (depending on where you are in the world) which means the results are not available until the birds are already in the race loft. Managers may, however, decide testing for this is worthwhile, depending on the prevalence and associated risk of the disease in their area.

On the third day the birds can be moved across into the main loft and their training commences. The holding loft should be disinfected before the next batch of youngsters is introduced with an effective disinfectant designed for this use; for example, Virkon F10. Mixing young babies with older squeakers in the one loft event loft is not ideal. The older youngsters will dominate the younger birds. It is better if the younger birds can be trained and fed separately for two to three weeks before being allowed to mix with the main group of more established youngsters. This two-to-three-week period gives the further opportunity for other undetected

health problems to appear. If they do appear, they will be confined to this batch, making control easier.

Unfortunately Herpes virus and Paratyphoid (due to Salmonella infection) can slip through undetected with this protocol. There are no foolproof live-bird diagnostic tests that will pick up these problems in birds that appear well. However once all the birds for the race have arrived and are settled and eating properly (for about one month) then in countries where a Paratyphoid vaccine is not available, a ten-day course of trimethoprim/sulphadiazine (for example, Sulpha AVS, 3g/4L) can be given. This is unlikely to eliminate Salmonella bacteria from every bird, but it is as much as can be practically done to decrease the chance of this infection leading to disease, and will do the birds no harm. At the completion of this course the birds are older and, with ongoing good care, particularly the avoidance of overcrowding, the maintenance of dry hygienic conditions, and the provision of a nutritious diet the disease is unlikely to cause problems.

In the following months as the birds mature, through to the day of the race, it is respiratory infection due to Chlamydia and Mycoplasma that is most likely to cause health problems.

Pigeons, once they are infected with Mycoplasma, are infected for life. If the birds get stressed then Mycoplasma can cause disease. When antibiotics are given they only restore health, they do not eradicate the Mycoplasma. The Mycoplasma then lies dormant until the birds again become ‘run down’. As the birds get older and develop their immunity it takes more stress to cause disease flare-ups.

Chlamydia will cycle through the growing babies. Text books tell us that if an individual pigeon is given doxycycline (the antibiotic of choice for Chlamydia) for 45 days, it has a 98% chance of actually clearing Chlamydia. If Chlamydia is cleared, then any immunity the pigeon has formed quickly fades and, in fact, has completely gone by six months thus leaving the bird vulnerable to re-infection. If a 45-day treatment could guarantee eradication of Chlamydia it may be worth considering.

However, this is unlikely to occur, and such a long course can compromise the moult and predispose the babies to other health problems such as bowel disease and interference with calcium metabolism. Also, it is worth considering that the birds are likely to be exposed to chlamydia on return to their home lofts after the event, and would be very vulnerable to infection because of their lowered immunity. In a one loft race a better approach is to allow exposure to Chlamydia. In the majority of birds it will not cause disease and, if the birds are being well cared for, will stimulate the development of immunity in them.

If Chlamydia does cause disease, the symptoms to look for are ‘eye colds’ and dirty ceres. If individual birds develop symptoms, these should be treated individually with doxycycline. Leave these birds in the loft and treat them each with doxycycline (for example, Doxyvet) 25mg/bird half a 50mg tablet once daily.

If more than 5–10% of birds are affected, give a flock treatment of doxycycline water-soluble powder (for example, Doxyvet 12%, 3g/2L) for four to seven days. If, however, this number of youngsters are affected, it indicates that something about the loft is interfering with the development of the birds’ immunity. The loft design and management should be reviewed for problems.

Diet

The growing babies should be offered a grain blend with approximately 15-20% protein, 5–7% fat and approximately 2950Kcal/kg of energy. As the moult is completed and the birds spend longer on the wing, the protein can be reduced to 12–14% and the energy increased to 3000Kcal/kg or higher, depending on the birds’ workload. Regular probiotics and a complete multivitamin and amino acid supplement given one day per week will help promote health.

As the day of the race approaches, race managers should consider having several of the birds checked by an avian veterinarian to make sure that there are no hidden health problems. It is better to do this and treat any health problems that are identified, rather than have a bad race and look for the cause later. Race managers should be discouraged from making totally independent decisions about health and treatment. Most race managers are experienced racing fanciers. They would not be in charge of a one loft race if they were not. However, not availing themselves of veterinary assistance leaves the race open to criticism if health problems occur.

One loft race managers should develop a working relationship with their local avian vet. Despite the best of care, simply because lots of birds from lots of different backgrounds are coming together in a single loft for nearly a year, the potential for health issues to arise is considerable. Most avian vets are keen to help with these events and many donate their services free as a service to the sport.

After the race

Fanciers are sometimes concerned that birds coming back to their loft after a one loft race may introduce disease into their own loft. In a well conducted one loft race with health management programs in place, this is unlikely. In a loft without health management programs the risk is significant. In particular, Paratyphoid and Herpes virus are a concern. In the end, fanciers will need to make the final decision here, based on each bird’s potential breeding value and their opinion of how the race has been conducted.

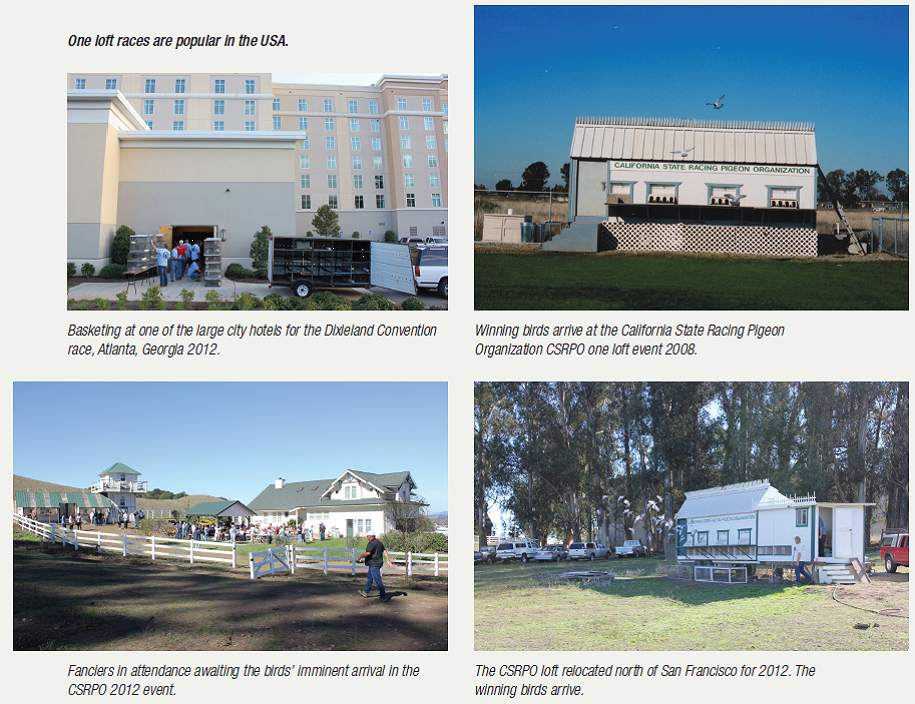

One loft races are great events that bring the pigeon community together. They allow the comparison, through direct competition, of birds from different areas and indeed different countries. They often generate a financial return that can be used to promote the sport, and also for other purposes. In many countries profits from one loft races are donated to charity. In America some fund educational scholarships to provide an opportunity for underprivileged youth. It is great to think that pigeon racing provides an education for some young people. One loft races with big entries and significant prize money have a ‘wow’ factor that helps advertise the sport in a positive way, and indeed draws the sport to many people’s attention. It is therefore important that they are conducted correctly.