- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

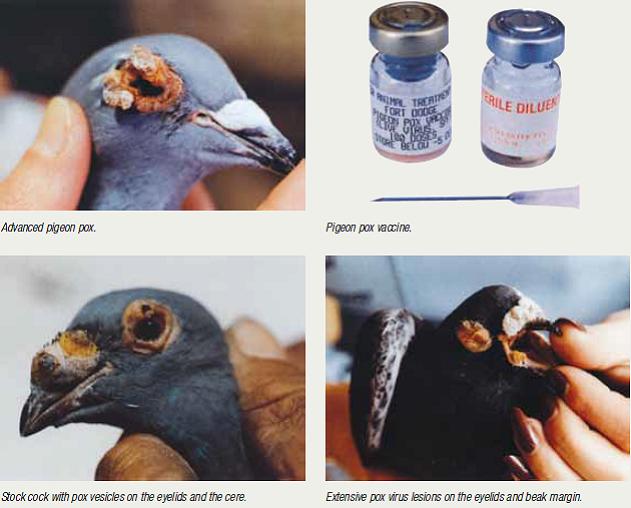

Pigeon pox is caused by a pox virus causing the development of dry crusty vesicles on the skin of pigeons (cutaneous pox) and yellow ‘cheesy’ plaques in the mouth (mucosal pox). The disease is usually regarded as a mild one, with the birds usually displaying mild or no signs of systemic disease.

There are a number of pox virus strains that vary in their potential to cause disease, with most strains causing only small vesicle formation. In fact, most clinically affected birds are infected by ‘escaped’ vaccine strains of the virus. Some strains, however, can cause severe soft tissue damage, leading to deformity of the eyelids and/or the tongue, or loss of sections or the entire beak. For the average pigeon fancier, however, pox is more a disease of inconvenience than one through which birds may be lost.

There are a number of pox virus strains that vary in their potential to cause disease, with most strains causing only small vesicle formation. In fact, most clinically affected birds are infected by ‘escaped’ vaccine strains of the virus. Some strains, however, can cause severe soft tissue damage, leading to deformity of the eyelids and/or the tongue, or loss of sections or the entire beak. For the average pigeon fancier, however, pox is more a disease of inconvenience than one through which birds may be lost.

Clinical course

Birds with the disease excrete the virus in tears, saliva and sometimes their droppings. At certain times the virus is also found in the blood. For birds to become infected, the virus needs a break in the skin or mucous membrane lining the mouth or eyelid to gain entry. The usual mode of transmission is fighting, when the beak of an infected bird simultaneously breaks the skin and leaves a small amount of saliva containing the virus behind. For this reason most lesions are around the eyes and beak, and cocks are more frequently infected.

Mosquitoes and other blood-sucking insects can also transmit the disease but can usually only gain access to the un-feathered parts of the body and so cause lesions around the head and on the legs. Mites can also spread the virus and can also cause lesions to develop on the feathered parts of the body. When non-infected and infected birds share drinkers or bath water, the virus can be transmitted through the water. When sharing bath water, the virus can infect the feather follicle at the time the feather is emerging, and cause vesicles to form here.

After infection the virus initially replicates at the site of inoculation. The virus then enters the blood stream (leading to a primary viraemia) before localising and replicating in the liver and spleen. The virus then re-enters the blood stream (leading to a secondary viraemia) before localising in the lungs, causing a viral bronchopneumonia. This all usually occurs within 14 days of infection. Birds usually show no symptoms. However some birds, particularly between 7 and 14 days post infection, can become a bit quiet and fluffed, develop a thirst and, rarely, some develop a uveitis (inflammation of the iris and it’s support structures which may make the iris become pale).

The virus runs a natural course of four to six weeks, with birds spontaneously recovering. Deaths rarely occur and when they do, are usually secondary to the physical bulk of the vesicle interfering with breathing, eating or vision. Fortunately, most affected birds develop only one or two small (approximately 3mm) vesicles and essentially remain well in themselves. Birds recovered from the disease develop a life-long immunity.

No direct treatment is available. However, as lesions in the mouth often become secondarily infected with bacteria and/or trichomonads, treating these will help to dry the lesion up, minimise tissue damage and make the bird more comfortable while the virus runs its course.

Birds with the disease excrete the virus in tears, saliva and sometimes their droppings. At certain times the virus is also found in the blood. For birds to become infected, the virus needs a break in the skin or mucous membrane lining the mouth or eyelid to gain entry. The usual mode of transmission is fighting, when the beak of an infected bird simultaneously breaks the skin and leaves a small amount of saliva containing the virus behind. For this reason most lesions are around the eyes and beak, and cocks are more frequently infected.

Mosquitoes and other blood-sucking insects can also transmit the disease but can usually only gain access to the un-feathered parts of the body and so cause lesions around the head and on the legs. Mites can also spread the virus and can also cause lesions to develop on the feathered parts of the body. When non-infected and infected birds share drinkers or bath water, the virus can be transmitted through the water. When sharing bath water, the virus can infect the feather follicle at the time the feather is emerging, and cause vesicles to form here.

After infection the virus initially replicates at the site of inoculation. The virus then enters the blood stream (leading to a primary viraemia) before localising and replicating in the liver and spleen. The virus then re-enters the blood stream (leading to a secondary viraemia) before localising in the lungs, causing a viral bronchopneumonia. This all usually occurs within 14 days of infection. Birds usually show no symptoms. However some birds, particularly between 7 and 14 days post infection, can become a bit quiet and fluffed, develop a thirst and, rarely, some develop a uveitis (inflammation of the iris and it’s support structures which may make the iris become pale).

The virus runs a natural course of four to six weeks, with birds spontaneously recovering. Deaths rarely occur and when they do, are usually secondary to the physical bulk of the vesicle interfering with breathing, eating or vision. Fortunately, most affected birds develop only one or two small (approximately 3mm) vesicles and essentially remain well in themselves. Birds recovered from the disease develop a life-long immunity.

No direct treatment is available. However, as lesions in the mouth often become secondarily infected with bacteria and/or trichomonads, treating these will help to dry the lesion up, minimise tissue damage and make the bird more comfortable while the virus runs its course.

|

Pigeon pox, rarely, can cause severe deformity. Here a pox vesicle has damaged the blood supply to the bones of the face and upper beak leading to the loss of these structures.

|

Pigeon pox vesicles on the beak of a 7-day-old youngster. For the vesicle to be this size at this age, this youngster must have become infected virtually in the first day of life.

|

Vaccination

Pigeon pox is controlled through vaccination.

Vaccination technique

When you receive your pigeon pox vaccine, you will find a small bottle with a dry orange pellet in its base, and either a second bottle or capped syringe containing a clear liquid. All should be stored in the freezer (not the fridge) until use. When it comes time to vaccinate the birds, take the tops off the bottle or syringe and pour the liquid on top of the orange pellet. This will dissolve over about a minute. The result is a thick orange liquid, not unlike tomato soup.

This is the vaccine.

The best place to vaccinate the birds is on the outside of the thigh. Avoid using the skin over thebre ast muscles as it is easy to push the needle in too far and damage the underlying flight muscles. Fold a few feathers back the ‘wrong’ way or pull a few feathers out to expose a bald area. This is an ideal vaccination site. The aim of inoculation is not to inject the vaccine but rather to create a puncture in the skin that mixes the vaccine with both air and blood. Dip the supplied needle into the vaccine and push the tip of the needle at an angle through the skin so that a small ‘blood ooze’ is created. Withdraw the needle, leaving a small bead of vaccine behind. The job is done.

Most birds will develop a small vaccine reaction – a white thickened skin nodule that may or may not be covered by a scab in 7–14 days. This heals over the following two to four weeks. The inoculated bird is infectious to other non-vaccinated pigeons while it has its nodule. After two to four weeks (up to six weeks after the original vaccination) the nodule heals. The bird is no longer infectious and develops a lifelong immunity.

Commonly asked questions

Is the vaccination harmful?

Absolutely not. Basically, there are two types of vaccines – live and killed. Live vaccines contain live viruses that deliberately infect the birds with a mild form of the disease. The live viruses in these live vaccines have been modified so that they are no longer able to cause disease. They do, however, stimulate the development of immunity not only to themselves but also to the nastier disease-causing strains. Killed vaccines just contain killed virus. The birds cannot become infected with these viruses but their immune systems are still exposed and an immunity will form. As a general rule, the level of immunity formed is much higher and lasts much longer with live vaccines such as the pigeon pox vaccine currently in use in Australia.

How often should I vaccinate my birds?

A single vaccination confers life time immunity, so just once is enough.

What happens if I vaccinate a bird that has already been vaccinated?

No harm done. If immune birds are vaccinated again, all that will happen is that they will not react to the vaccine; no thickened nodule or scab will form at the inoculation site. Because they are immune the modified live virus in the vaccine cannot infect them. If there is any doubt as to whether a bird has been vaccinated or not, it is safer to re-vaccinate the bird to make sure that it is immune rather than not to vaccinate.

How young can I vaccinate a pigeon?

The recommendation is that all pigeons should be over six weeks of age when inoculated. Often, however, much younger pigeons are vaccinated, even at one to two weeks of age in the nest, without ill effect. As pigeons grow, their immune systems naturally become more and more mature and so they are better able to form a strong immunity to pox virus after vaccination. Also young growing pigeons are facing multiple stresses. Vaccinating with a live vaccine, although modified, is another stress. All together these stresses have the potential to compromise the growing pigeon’s development.

The usual advice is to wait until the youngsters are settled in the racing loft, eating and drinking properly and with their own perches. Usually by six weeks of age this has occurred. However, in the face of an outbreak younger birds are vaccinated. If they are well otherwise and are being well cared for it is unlikely that this will do them any harm.

Can I give my birds a bath after vaccination?

If all of the birds have been vaccinated there is no problem. Pox virus can spread through the bath water and infect non-vaccinated birds. Therefore recently vaccinated (within the last six weeks and still carrying a vaccination nodule or scab) and non-vaccinated birds should not be bathed together. If, however, all birds have been vaccinated there is no problem.

Can I loft fly or toss recently vaccinated birds?

After vaccination, birds, for the most part, may be treated normally. They can be fed and loft flown normally and, indeed, for young racers, I believe it is important that they be kept in their loft routine. Between one and two weeks after inoculation a reaction to the vaccine will develop at the inoculation site. This can vary from a very small thickening in the skin to a large raised nodule covered by a scab. This reaction develops as the bird is reacting to the vaccine and starting to form an immune response to it. Some birds develop a slight fever during this time. These birds will appear a bit fluffed and will be a bit less active in the loft. These birds may also drink a bit more and as a result develop watery droppings. This stage is transient and mild.

Once the nodule has finished developing the birds are again well. Up to seven days and after fourteen days birds can be managed normally. During this time there is no problem loft flying the birds but it is best not to toss them during this time. After vaccination, manage the team of youngsters normally but be mindful that between seven and fourteen days some might be feeling a bit ‘off’. Also at this time, the uvea (the iris and its support structures in the eye) in some birds can become inflamed. This makes the eyes a bit light

sensitive and ‘squinty’. If flown late in the day, when the shadows are starting to get long, the birds can become ‘jumpy’ and a ‘fly-away’ is possible.

Can I race recently vaccinated birds?

No. Clubs and federations throughout Australia do not allow birds with obvious transmissible disease to be entered into races. Pigeons that are still carrying their scabs after inoculation are infectious to other pigeons (that have not been inoculated) and therefore should not be allowed entry.

I have heard that vaccinating birds can give them a boost and help to improve race results. Is this true?

To some extent, yes. As pigeons pass the 14-day stage after inoculation and their reaction at the inoculation site starts to heal, their immune systems are ‘switched on’ and in some birds there does appear to be a short time where a period of ‘super health’ is achieved. Some fanciers have done well during this time and have at least partially attributed their good results to this. However, this practice should be discouraged. Birds will react differently to the vaccine and, while some birds may be very good others may react more slowly, have a slight fever and be a bit unwell. These birds will be at risk of being lost if raced. Hopefully, vaccinated birds would be detected by handlers during race marking. There will always be fanciers, looking for an advantage, who inoculate in inconspicuous locations. Federations need to be vigilant against this.

Should I vaccinate birds that appear unwell?

Definitely not; for two reasons. Birds obviously unwell with one infection such as ‘eye colds’ will not form a good immunity to a second (that is, the virus in the pox vaccine). Also vaccination is another superimposed stress and can exacerbate pre-existent health problems. For example, if a group of young pigeons are struggling to form immunity and recover from an outbreak of canker or ‘eye colds’, vaccinating them will only make this harder for them and will likely precipitate an outbreak of this problem.

If my birds become unwell after vaccination can I medicate them?

Yes, pigeon pox is a viral disease and the commonly used medications, even antibiotics, have no effect on it. If pigeons become unwell after vaccination the cause should be investigated and appropriate treatment given. In fact, the immunity they form will be better this way.

I vaccinated my birds and I cannot see any ‘takes’. Has the vaccine worked?

Maybe not. Birds should be checked 10–14 days after inoculation for ‘takes’; that is, nodular thickening with or without a scab at the inoculation site. Not every bird will necessarily have this but the majority should. Not having a nodular thickening or a scab arouses suspicion that the vaccine may not have worked. By far the most common cause of vaccine failure is that the vaccine has become warm and thus inactivated; that is, died, prior to use.

The vaccine is a living viral culture which is killed by heat and UV light. It should be stored in the freezer, reconstituted immediately prior to use and kept cool and out of direct sunlight while being used. Prolonged exposure to heat and UV light gradually kills the virus in the vaccine meaning that more and more vaccine needs to be inserted at the inoculation site to provide sufficient live virus to form an immune response. Eventually all virus will die. There will be nothing for the pigeon to react against and no immunity will form.

There is usually no problem with use or storage once the vaccine has reached the home loft but keeping the vaccine cool during transport and posting can be a problem because of the shipping distances involved and the hot weather of Australia. Having said that, when compared to other viruses pox viruses are fairly tough and there are instances of vaccine not being refrigerated for several days (and even being reconstituted with boiling water) and still working. Every effort should be made, however, to keep the vaccine cold.

Other causes of vaccine failure include poor vaccination technique or inoculating birds that have diseases that interfere with the functioning of the immune system. In particular, Circo virus infection is becoming more and more relevant here.

Is it ok to share my vaccine with other club members?

Absolutely not. This is a really silly activity that has become acceptable practice in some parts of Australia. There are many diseases in young pigeons that are spread through the blood – common ones include Circo virus, Herpes virus, Chlamydia and Salmonella. If you are the last ‘cab off the rank’, in effect you are inoculating birds with all the germs found in all the pigeons that have been previously inoculated with that batch of vaccine. Direct inoculation into the bloodstream is a really great way of introducing these diseases into

your birds. For the sake of the cost of the vaccine, buy your own bottle of vaccine or, if you must share, only share with a fancier whom you know has no health problems in his birds.

Can I re-freeze and re-use the same vaccine?

This should not be a problem provided the vaccine has not been in full sun for an extended period or been allowed to get hot during use. A good trick is to pack a stubby holder with ice and have the vaccine sitting in this while inoculating the birds. If after use you think that the vaccine is fine, re-cap the vaccine bottle and place it back in the freezer. It will then store satisfactorily. It is always a bother to re-use a bottle in this way, and then find that it has not worked. For this reason it is a good idea, when re-using vaccine, to just vaccinate 2 to 3 birds initially and check these ten days later. If they have taken, then you know the vaccine is still viable and you can go ahead and vaccinate the rest of the team.

Is there any treatment for pigeons with pigeon pox?

No. There is no direct treatment for a pox virus. Sometimes, however, where pox vesicles form inside the mouth, because of the warm wet environment there, they can become secondarily infected with bacteria and canker organisms. Sometimes these birds will benefit from a short course of anti-canker medication and an antibiotic. This will help to dry up the lesion and make the bird more comfortable while the virus runs its course. Lesions on the skin are best left alone. Attempting to remove them or treating with various

topical agents tends to cause more tissue destruction and delay healing.

Pigeon pox is controlled through vaccination.

Vaccination technique

When you receive your pigeon pox vaccine, you will find a small bottle with a dry orange pellet in its base, and either a second bottle or capped syringe containing a clear liquid. All should be stored in the freezer (not the fridge) until use. When it comes time to vaccinate the birds, take the tops off the bottle or syringe and pour the liquid on top of the orange pellet. This will dissolve over about a minute. The result is a thick orange liquid, not unlike tomato soup.

This is the vaccine.

The best place to vaccinate the birds is on the outside of the thigh. Avoid using the skin over thebre ast muscles as it is easy to push the needle in too far and damage the underlying flight muscles. Fold a few feathers back the ‘wrong’ way or pull a few feathers out to expose a bald area. This is an ideal vaccination site. The aim of inoculation is not to inject the vaccine but rather to create a puncture in the skin that mixes the vaccine with both air and blood. Dip the supplied needle into the vaccine and push the tip of the needle at an angle through the skin so that a small ‘blood ooze’ is created. Withdraw the needle, leaving a small bead of vaccine behind. The job is done.

Most birds will develop a small vaccine reaction – a white thickened skin nodule that may or may not be covered by a scab in 7–14 days. This heals over the following two to four weeks. The inoculated bird is infectious to other non-vaccinated pigeons while it has its nodule. After two to four weeks (up to six weeks after the original vaccination) the nodule heals. The bird is no longer infectious and develops a lifelong immunity.

Commonly asked questions

Is the vaccination harmful?

Absolutely not. Basically, there are two types of vaccines – live and killed. Live vaccines contain live viruses that deliberately infect the birds with a mild form of the disease. The live viruses in these live vaccines have been modified so that they are no longer able to cause disease. They do, however, stimulate the development of immunity not only to themselves but also to the nastier disease-causing strains. Killed vaccines just contain killed virus. The birds cannot become infected with these viruses but their immune systems are still exposed and an immunity will form. As a general rule, the level of immunity formed is much higher and lasts much longer with live vaccines such as the pigeon pox vaccine currently in use in Australia.

How often should I vaccinate my birds?

A single vaccination confers life time immunity, so just once is enough.

What happens if I vaccinate a bird that has already been vaccinated?

No harm done. If immune birds are vaccinated again, all that will happen is that they will not react to the vaccine; no thickened nodule or scab will form at the inoculation site. Because they are immune the modified live virus in the vaccine cannot infect them. If there is any doubt as to whether a bird has been vaccinated or not, it is safer to re-vaccinate the bird to make sure that it is immune rather than not to vaccinate.

How young can I vaccinate a pigeon?

The recommendation is that all pigeons should be over six weeks of age when inoculated. Often, however, much younger pigeons are vaccinated, even at one to two weeks of age in the nest, without ill effect. As pigeons grow, their immune systems naturally become more and more mature and so they are better able to form a strong immunity to pox virus after vaccination. Also young growing pigeons are facing multiple stresses. Vaccinating with a live vaccine, although modified, is another stress. All together these stresses have the potential to compromise the growing pigeon’s development.

The usual advice is to wait until the youngsters are settled in the racing loft, eating and drinking properly and with their own perches. Usually by six weeks of age this has occurred. However, in the face of an outbreak younger birds are vaccinated. If they are well otherwise and are being well cared for it is unlikely that this will do them any harm.

Can I give my birds a bath after vaccination?

If all of the birds have been vaccinated there is no problem. Pox virus can spread through the bath water and infect non-vaccinated birds. Therefore recently vaccinated (within the last six weeks and still carrying a vaccination nodule or scab) and non-vaccinated birds should not be bathed together. If, however, all birds have been vaccinated there is no problem.

Can I loft fly or toss recently vaccinated birds?

After vaccination, birds, for the most part, may be treated normally. They can be fed and loft flown normally and, indeed, for young racers, I believe it is important that they be kept in their loft routine. Between one and two weeks after inoculation a reaction to the vaccine will develop at the inoculation site. This can vary from a very small thickening in the skin to a large raised nodule covered by a scab. This reaction develops as the bird is reacting to the vaccine and starting to form an immune response to it. Some birds develop a slight fever during this time. These birds will appear a bit fluffed and will be a bit less active in the loft. These birds may also drink a bit more and as a result develop watery droppings. This stage is transient and mild.

Once the nodule has finished developing the birds are again well. Up to seven days and after fourteen days birds can be managed normally. During this time there is no problem loft flying the birds but it is best not to toss them during this time. After vaccination, manage the team of youngsters normally but be mindful that between seven and fourteen days some might be feeling a bit ‘off’. Also at this time, the uvea (the iris and its support structures in the eye) in some birds can become inflamed. This makes the eyes a bit light

sensitive and ‘squinty’. If flown late in the day, when the shadows are starting to get long, the birds can become ‘jumpy’ and a ‘fly-away’ is possible.

Can I race recently vaccinated birds?

No. Clubs and federations throughout Australia do not allow birds with obvious transmissible disease to be entered into races. Pigeons that are still carrying their scabs after inoculation are infectious to other pigeons (that have not been inoculated) and therefore should not be allowed entry.

I have heard that vaccinating birds can give them a boost and help to improve race results. Is this true?

To some extent, yes. As pigeons pass the 14-day stage after inoculation and their reaction at the inoculation site starts to heal, their immune systems are ‘switched on’ and in some birds there does appear to be a short time where a period of ‘super health’ is achieved. Some fanciers have done well during this time and have at least partially attributed their good results to this. However, this practice should be discouraged. Birds will react differently to the vaccine and, while some birds may be very good others may react more slowly, have a slight fever and be a bit unwell. These birds will be at risk of being lost if raced. Hopefully, vaccinated birds would be detected by handlers during race marking. There will always be fanciers, looking for an advantage, who inoculate in inconspicuous locations. Federations need to be vigilant against this.

Should I vaccinate birds that appear unwell?

Definitely not; for two reasons. Birds obviously unwell with one infection such as ‘eye colds’ will not form a good immunity to a second (that is, the virus in the pox vaccine). Also vaccination is another superimposed stress and can exacerbate pre-existent health problems. For example, if a group of young pigeons are struggling to form immunity and recover from an outbreak of canker or ‘eye colds’, vaccinating them will only make this harder for them and will likely precipitate an outbreak of this problem.

If my birds become unwell after vaccination can I medicate them?

Yes, pigeon pox is a viral disease and the commonly used medications, even antibiotics, have no effect on it. If pigeons become unwell after vaccination the cause should be investigated and appropriate treatment given. In fact, the immunity they form will be better this way.

I vaccinated my birds and I cannot see any ‘takes’. Has the vaccine worked?

Maybe not. Birds should be checked 10–14 days after inoculation for ‘takes’; that is, nodular thickening with or without a scab at the inoculation site. Not every bird will necessarily have this but the majority should. Not having a nodular thickening or a scab arouses suspicion that the vaccine may not have worked. By far the most common cause of vaccine failure is that the vaccine has become warm and thus inactivated; that is, died, prior to use.

The vaccine is a living viral culture which is killed by heat and UV light. It should be stored in the freezer, reconstituted immediately prior to use and kept cool and out of direct sunlight while being used. Prolonged exposure to heat and UV light gradually kills the virus in the vaccine meaning that more and more vaccine needs to be inserted at the inoculation site to provide sufficient live virus to form an immune response. Eventually all virus will die. There will be nothing for the pigeon to react against and no immunity will form.

There is usually no problem with use or storage once the vaccine has reached the home loft but keeping the vaccine cool during transport and posting can be a problem because of the shipping distances involved and the hot weather of Australia. Having said that, when compared to other viruses pox viruses are fairly tough and there are instances of vaccine not being refrigerated for several days (and even being reconstituted with boiling water) and still working. Every effort should be made, however, to keep the vaccine cold.

Other causes of vaccine failure include poor vaccination technique or inoculating birds that have diseases that interfere with the functioning of the immune system. In particular, Circo virus infection is becoming more and more relevant here.

Is it ok to share my vaccine with other club members?

Absolutely not. This is a really silly activity that has become acceptable practice in some parts of Australia. There are many diseases in young pigeons that are spread through the blood – common ones include Circo virus, Herpes virus, Chlamydia and Salmonella. If you are the last ‘cab off the rank’, in effect you are inoculating birds with all the germs found in all the pigeons that have been previously inoculated with that batch of vaccine. Direct inoculation into the bloodstream is a really great way of introducing these diseases into

your birds. For the sake of the cost of the vaccine, buy your own bottle of vaccine or, if you must share, only share with a fancier whom you know has no health problems in his birds.

Can I re-freeze and re-use the same vaccine?

This should not be a problem provided the vaccine has not been in full sun for an extended period or been allowed to get hot during use. A good trick is to pack a stubby holder with ice and have the vaccine sitting in this while inoculating the birds. If after use you think that the vaccine is fine, re-cap the vaccine bottle and place it back in the freezer. It will then store satisfactorily. It is always a bother to re-use a bottle in this way, and then find that it has not worked. For this reason it is a good idea, when re-using vaccine, to just vaccinate 2 to 3 birds initially and check these ten days later. If they have taken, then you know the vaccine is still viable and you can go ahead and vaccinate the rest of the team.

Is there any treatment for pigeons with pigeon pox?

No. There is no direct treatment for a pox virus. Sometimes, however, where pox vesicles form inside the mouth, because of the warm wet environment there, they can become secondarily infected with bacteria and canker organisms. Sometimes these birds will benefit from a short course of anti-canker medication and an antibiotic. This will help to dry up the lesion and make the bird more comfortable while the virus runs its course. Lesions on the skin are best left alone. Attempting to remove them or treating with various

topical agents tends to cause more tissue destruction and delay healing.

Management of an outbreak

Out of the racing season

If an outbreak occurs out of the racing season, provided birds are over six weeks of age and it is at least six weeks before racing, the best thing to do is simply vaccinate the birds. If vaccinating in the face of an outbreak, birds already with the disease should not be vaccinated.

Out of the racing season

If an outbreak occurs out of the racing season, provided birds are over six weeks of age and it is at least six weeks before racing, the best thing to do is simply vaccinate the birds. If vaccinating in the face of an outbreak, birds already with the disease should not be vaccinated.

During racing

If an outbreak occurs during racing, the situation is not as easy. The usual reason for vaccinating is to prevent just this occurrence. As mentioned above, the disease is rarely fatal and is more one of inconvenience. If birds appear with pox in the racing loft during the season, the flier has one of two options:

1. To vaccinate all birds. This means that between four and six weeks of competition are lost and so this option is rarely taken.

2. To separate affected birds from the rest of the team. These birds can be fed, watered and exercised separately and when recovered after four to six weeks can be brought back into the team as fresh birds. The difficulty here is that the virus has an incubation period of ten days. By the time it is realised that a bird has pox, it may have already pecked or in some other way infected several birds in the loft, which are now incubating the disease and spreading it further. Eventually, most of the team ends up with the disease.

3. In many lofts, however, this does represent an effective means of containment and as soon as the fancier has had a ten-day break without any new cases, he or she knows that the outbreak is controlled. Recovered birds are competitive. In 1995, no pox vaccine was available in Australia. I chose this option to control the spread of the infection and won at the distance on two occasions with birds that earlier in the season had had pigeon pox and had to be spelled.

Outbreaks that occur during breeding are usually started by mosquitoes as there is not the same exposure to birds from other lofts as there is in the racing loft. Individual birds that become infected are usually best immediately separated in order to minimise spread of the disease. Mosquitoes can be discouraged by regular spraying with permethrin solution.

Conditions that look similar

Canker is the disease with which pox is most commonly confused. When pox appears on the skin (the cutaneous form) the dry crusty lumpy appearance of the lesion is usually diagnostic. However, when it occurs in the mouth (mucosal pox) the lesion looks like a yellow plaque, which is easy to confuse with canker. Indeed, in some birds, I can only tell the difference by swabbing the lesion and looking under the microscope. Often, the fancier is alerted to mucosal pox by no response to anti-canker medication. There are three simple loft based tests that a fancier can use to distinguish the two:

1. The site of the lesion. If an imaginary line is drawn through the base of the bird’s beak, then any lesions between

this line and the tip of the beak are likely to be pox vesicles. This area is too hostile and exposed for Trichomonad

organisms to survive. Conversely, lesions on the throat side of this line are likely to be canker.

2. Attachment to surrounding tissue. As canker lesions invade, there is often a fragile line of inflammation at the

edge of the lesion, which enables separation of the canker nodule from the surrounding tissue. The pox lesion is

a vesicle or blister of the mouth lining itself, and so cannot be separated from it.

3. General health. Birds with canker look sick while birds with pox are usually well in themselves.

If an outbreak occurs during racing, the situation is not as easy. The usual reason for vaccinating is to prevent just this occurrence. As mentioned above, the disease is rarely fatal and is more one of inconvenience. If birds appear with pox in the racing loft during the season, the flier has one of two options:

1. To vaccinate all birds. This means that between four and six weeks of competition are lost and so this option is rarely taken.

2. To separate affected birds from the rest of the team. These birds can be fed, watered and exercised separately and when recovered after four to six weeks can be brought back into the team as fresh birds. The difficulty here is that the virus has an incubation period of ten days. By the time it is realised that a bird has pox, it may have already pecked or in some other way infected several birds in the loft, which are now incubating the disease and spreading it further. Eventually, most of the team ends up with the disease.

3. In many lofts, however, this does represent an effective means of containment and as soon as the fancier has had a ten-day break without any new cases, he or she knows that the outbreak is controlled. Recovered birds are competitive. In 1995, no pox vaccine was available in Australia. I chose this option to control the spread of the infection and won at the distance on two occasions with birds that earlier in the season had had pigeon pox and had to be spelled.

Outbreaks that occur during breeding are usually started by mosquitoes as there is not the same exposure to birds from other lofts as there is in the racing loft. Individual birds that become infected are usually best immediately separated in order to minimise spread of the disease. Mosquitoes can be discouraged by regular spraying with permethrin solution.

Conditions that look similar

Canker is the disease with which pox is most commonly confused. When pox appears on the skin (the cutaneous form) the dry crusty lumpy appearance of the lesion is usually diagnostic. However, when it occurs in the mouth (mucosal pox) the lesion looks like a yellow plaque, which is easy to confuse with canker. Indeed, in some birds, I can only tell the difference by swabbing the lesion and looking under the microscope. Often, the fancier is alerted to mucosal pox by no response to anti-canker medication. There are three simple loft based tests that a fancier can use to distinguish the two:

1. The site of the lesion. If an imaginary line is drawn through the base of the bird’s beak, then any lesions between

this line and the tip of the beak are likely to be pox vesicles. This area is too hostile and exposed for Trichomonad

organisms to survive. Conversely, lesions on the throat side of this line are likely to be canker.

2. Attachment to surrounding tissue. As canker lesions invade, there is often a fragile line of inflammation at the

edge of the lesion, which enables separation of the canker nodule from the surrounding tissue. The pox lesion is

a vesicle or blister of the mouth lining itself, and so cannot be separated from it.

3. General health. Birds with canker look sick while birds with pox are usually well in themselves.