- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

Many of the factors that influence the health of our birds are hidden to the naked eye and it is only through veterinary examination that these are revealed. However, there are external signs that reflect whether or not various internal systems are working well. The fancier

should learn how to identify and interpret these signs. This chapter deals with indicators of health involving the head and throat.

Tonsils

Avian ‘tonsils’

The term ‘tonsils’ when applied to birds would make most vets cringe. This is because birds don’t have tonsils in the strictest sense of the word. What birds do have are clumps of cells called lymphoid aggregates. These lymphoid aggregates occur within various tissues throughout the body and behave in a similar way to a mammal’s tonsils. When challenged by a foreign pathogen (disease-causing agent) these clumps of cells can elicit an immune response. Areas containing large numbers of lymphoid aggregates (described as lymphoid tissue) can become red and swollen in the process. In mammals some lymphoid tissue is organised

into formal structures that are called tonsils. This is not the case in birds. The areas most familiar to fanciers that contain large numbers of lymphoid aggregates are:

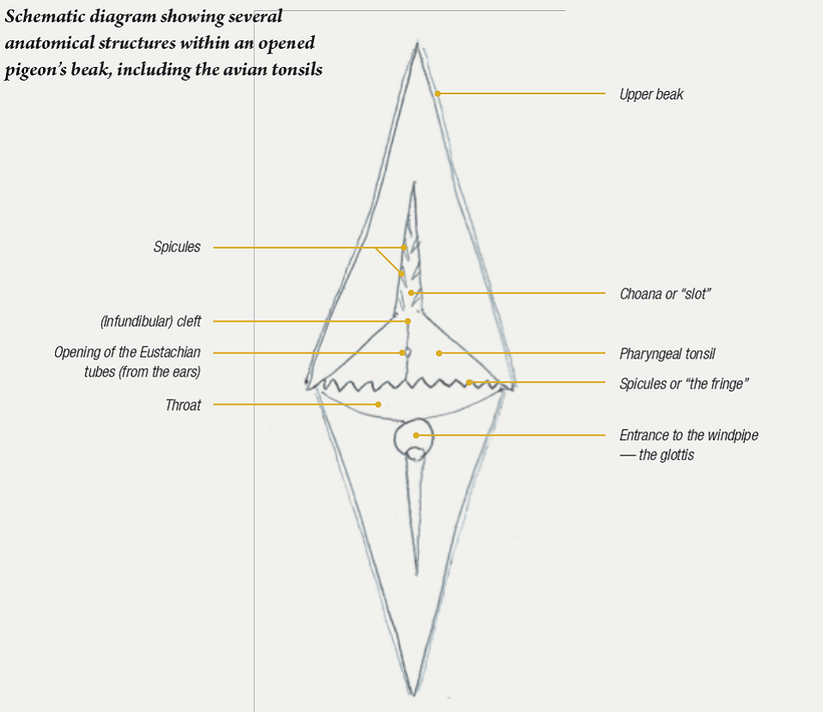

1. The piece of tissue about 2mm across at the base of the tongue on the leading edge of the windpipe (called the laryngeal mound).

2. The large triangular wedge of tissue (called the pharyngeal tonsil) that runs back from the choana (the ‘slot’) across the palate to its posterior edge where the spicules (the ‘fringe’) are located.

3. The area on the underside of the third eyelid (called the Harderian gland).

Although not strictly correct in the veterinary sense, for ease of understanding, areas of tissue that contain

large numbers of lymphoid aggregates in birds can be loosely described as “avian tonsils”.

should learn how to identify and interpret these signs. This chapter deals with indicators of health involving the head and throat.

Tonsils

Avian ‘tonsils’

The term ‘tonsils’ when applied to birds would make most vets cringe. This is because birds don’t have tonsils in the strictest sense of the word. What birds do have are clumps of cells called lymphoid aggregates. These lymphoid aggregates occur within various tissues throughout the body and behave in a similar way to a mammal’s tonsils. When challenged by a foreign pathogen (disease-causing agent) these clumps of cells can elicit an immune response. Areas containing large numbers of lymphoid aggregates (described as lymphoid tissue) can become red and swollen in the process. In mammals some lymphoid tissue is organised

into formal structures that are called tonsils. This is not the case in birds. The areas most familiar to fanciers that contain large numbers of lymphoid aggregates are:

1. The piece of tissue about 2mm across at the base of the tongue on the leading edge of the windpipe (called the laryngeal mound).

2. The large triangular wedge of tissue (called the pharyngeal tonsil) that runs back from the choana (the ‘slot’) across the palate to its posterior edge where the spicules (the ‘fringe’) are located.

3. The area on the underside of the third eyelid (called the Harderian gland).

Although not strictly correct in the veterinary sense, for ease of understanding, areas of tissue that contain

large numbers of lymphoid aggregates in birds can be loosely described as “avian tonsils”.

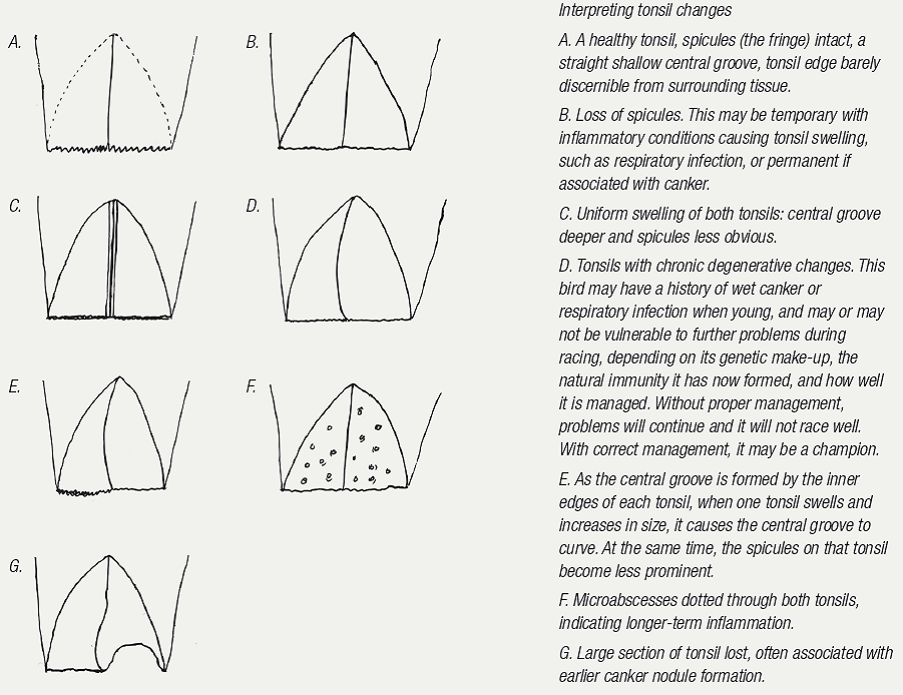

After opening the bird’s beak, the avian tonsils are important structures to look at initially. The tonsils are the visible part of the bird’s immune system and can react to potentially harmful organisms. When challenged with infectious agents, these areas initially swell. If infection progresses small pockets of inflammatory debris start to appear. These ‘pimples’ or abscesses within the tonsil tissue appear as small white to yellow dots scattered throughout the tonsil tissue. These birds have tonsillitis, i.e. inflammation of the tonsils. Possible causes include bacterial or yeast infections, wet canker or the agents of respiratory infection – Chlamydia and Mycoplasma. Wet canker and/or respiratory infection tend to be the most likely causes. Testing, involving microscopic examination of crop flushes, Chlamydia tests and bacterial cultures etc. are required to identify the cause.

As the pharyngeal tonsils swell, if both sides do so uniformly, the central groove (infundibular cleft) becomes deeper. If one side enlarges more than the other, the groove will deviate to one side, with the swollen segment pushing across to the other side. This swelling may cause the “fringe” to disappear. If associated with respiratory infection, then, as the swelling subsides, the “fringe” will reappear. However, if the tonsillitis is due to canker, sections of the “fringe” and, indeed, the tonsil itself may be lost permanently. Tonsil abscesses associated with wet canker are yellow and bulge out from the tonsil tissue when the disease is active, i.e. the trichomonad count is high. The immediately surrounding tonsil tissue forms a red zone of inflammation. At this stage, as a consequence of the wet canker flare up, the birds cannot perform. As the condition resolves and the tonsil is no longer inflamed, the abscesses gradually lose their colour, changing to white, and then become a translucent plaque on the tonsil. At this stage, the infection is no longer active and cannot affect race form. The spots may, however, take weeks to disappear once the infection has resolved.

As the pharyngeal tonsils swell, if both sides do so uniformly, the central groove (infundibular cleft) becomes deeper. If one side enlarges more than the other, the groove will deviate to one side, with the swollen segment pushing across to the other side. This swelling may cause the “fringe” to disappear. If associated with respiratory infection, then, as the swelling subsides, the “fringe” will reappear. However, if the tonsillitis is due to canker, sections of the “fringe” and, indeed, the tonsil itself may be lost permanently. Tonsil abscesses associated with wet canker are yellow and bulge out from the tonsil tissue when the disease is active, i.e. the trichomonad count is high. The immediately surrounding tonsil tissue forms a red zone of inflammation. At this stage, as a consequence of the wet canker flare up, the birds cannot perform. As the condition resolves and the tonsil is no longer inflamed, the abscesses gradually lose their colour, changing to white, and then become a translucent plaque on the tonsil. At this stage, the infection is no longer active and cannot affect race form. The spots may, however, take weeks to disappear once the infection has resolved.

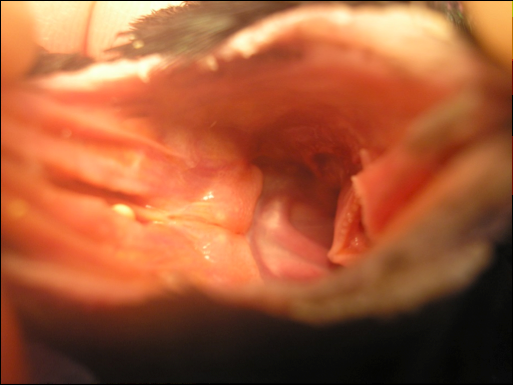

|

Tonsillitis – the inflamed tonsils are visible as the triangular bright pink area in the roof of the mouth. The row of spicules, known as ‘the fringe’ has been lost. This bird has an established respiratory infection. The glottis (entrance to the windpipe) is rounded, the mucous membranes (lining) of the mouth are slightly blue and the tongue tip is discoloured – all consistent with increased respiratory effort and decreased oxygen levels in the blood. |

Teams containing birds with white spots in their tonsils therefore alert us to a probable wet canker flare up in the past and also warn of the possibility of repeat flare ups with the stress of racing ahead. Where individual birds are developing new yellow spots in the tonsil, the fancier should, if racing, organise an immediate crop flush or, alternatively, instigate treatment with an effective canker medication and seek veterinary advice.

As the laryngeal mound is at the entrance of the wind pipe, which is part of the respiratory tract, abscesses here are usually associated with a respiratory infection.

As the laryngeal mound is at the entrance of the wind pipe, which is part of the respiratory tract, abscesses here are usually associated with a respiratory infection.

Mucus

The quantity and appearance of mucus in the throat can also give an indication of the bird’s health. In health, the throat should appear wet but have no accumulation of mucus apparent. The amount of clear mucus can marginally increase in birds that are ‘just not right’ and is more often than not associated with stress-producing circumstances, such as problems with the loft environment or a recent flaw in the birds’ management. Rather than reach for medication, correction of the underlying problem is the more appropriate course

of action. When bubbly clear mucus starts accumulating at the back of the throat, particularly if the throat appears red and inflamed, this is indicative of inflammation in the area. This is almost invariably associated with wet canker. The fancier should monitor the birds for other signs associated with wet canker, as discussed in other chapters, and seek veterinary advice. The mucus becoming white, coloured or turbid often indicates secondary bacterial infection and is usually due to E. coli.

Nostril discharge – a respiratory infection?

Not all discharges from the nostrils are associated with respiratory infection. It is not unusual to find dried discharge or clear fluid at the opening of the cere in short-faced breeds such as Turbits, Owls and Oriental Frills. The sinuses that drain under the cere release fluid from their lining, which evaporates as the birds breathe. In short-faced breeds, the sinuses are compressed and there is not the same opportunity for this fluid to evaporate away, with the result that some trickles from the nostrils. The same occurs in short-faced breeds of dogs, such as the Boxer and the Pug, and in Persian cats. A similar mechanism occurs in race birds that are exercised on cold mornings. The moisture in the warm, expired air condenses on the cold surface of the beak, leaving a wet ring at the opening of the cere.

With respiratory infection, thick, white slime can accumulate in the throat. This slime, however, does not form in the throat but, rather, moves into the throat from neighbouring respiratory structures, namely the sinuses and trachea. Pigeons have multiple sinuses in the head, connecting with each other via fine ducts. These are each lined by a sensory membrane, which produces mucus in response to irritation. They drain into the ‘slot’ (choana) in the roof of the mouth and also the back of the throat.

The quantity and appearance of mucus in the throat can also give an indication of the bird’s health. In health, the throat should appear wet but have no accumulation of mucus apparent. The amount of clear mucus can marginally increase in birds that are ‘just not right’ and is more often than not associated with stress-producing circumstances, such as problems with the loft environment or a recent flaw in the birds’ management. Rather than reach for medication, correction of the underlying problem is the more appropriate course

of action. When bubbly clear mucus starts accumulating at the back of the throat, particularly if the throat appears red and inflamed, this is indicative of inflammation in the area. This is almost invariably associated with wet canker. The fancier should monitor the birds for other signs associated with wet canker, as discussed in other chapters, and seek veterinary advice. The mucus becoming white, coloured or turbid often indicates secondary bacterial infection and is usually due to E. coli.

Nostril discharge – a respiratory infection?

Not all discharges from the nostrils are associated with respiratory infection. It is not unusual to find dried discharge or clear fluid at the opening of the cere in short-faced breeds such as Turbits, Owls and Oriental Frills. The sinuses that drain under the cere release fluid from their lining, which evaporates as the birds breathe. In short-faced breeds, the sinuses are compressed and there is not the same opportunity for this fluid to evaporate away, with the result that some trickles from the nostrils. The same occurs in short-faced breeds of dogs, such as the Boxer and the Pug, and in Persian cats. A similar mechanism occurs in race birds that are exercised on cold mornings. The moisture in the warm, expired air condenses on the cold surface of the beak, leaving a wet ring at the opening of the cere.

With respiratory infection, thick, white slime can accumulate in the throat. This slime, however, does not form in the throat but, rather, moves into the throat from neighbouring respiratory structures, namely the sinuses and trachea. Pigeons have multiple sinuses in the head, connecting with each other via fine ducts. These are each lined by a sensory membrane, which produces mucus in response to irritation. They drain into the ‘slot’ (choana) in the roof of the mouth and also the back of the throat.

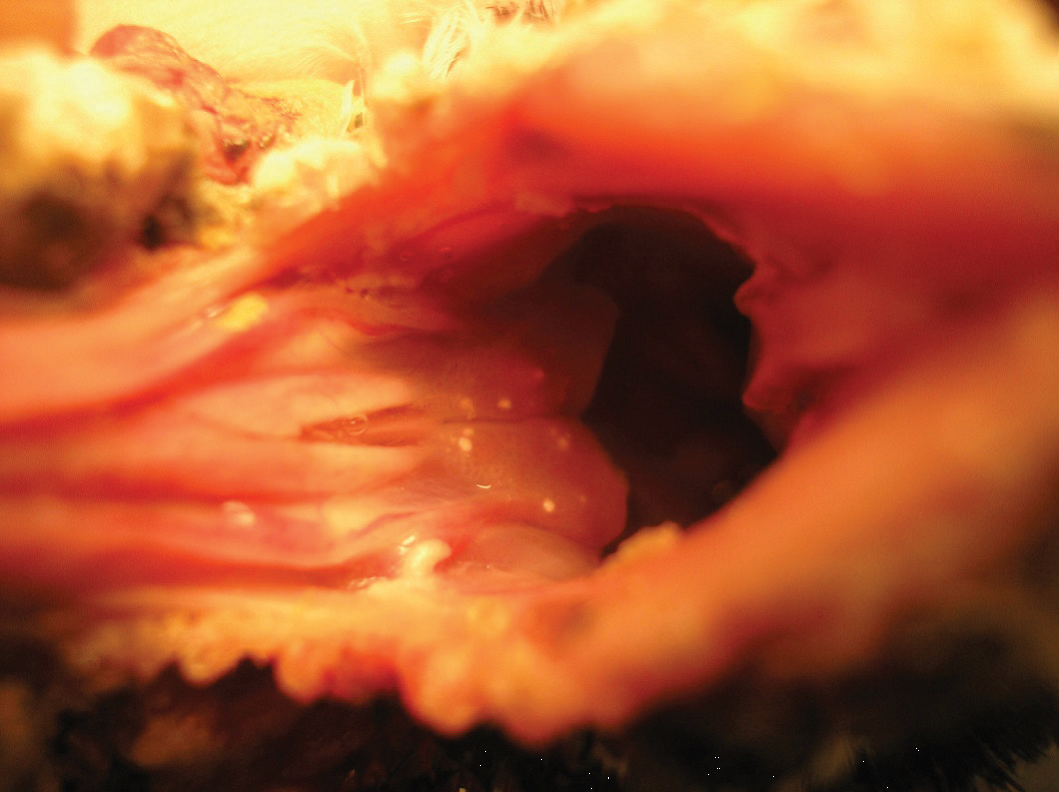

|

The throat of a bird with a severe upper respiratory infection. The front of the choana (the ‘slot) is swollen closed and bubbly mucus is draining from the sinuses through the choana into the mouth. The pharyngeal tonsil is swollen and red and is readily visible as the triangular structure in the bird’s palate. The spicules (the ‘fringe’) have been destroyed in the inflammatory process and are no longer visible. The lining of the mouth has a bluish colour, indicating reduced blood oxygen levels. |

With inflammation of these sinuses (sinusitis), as in a human with a cold, mucus forms. In pigeons this mucus then drains through the ‘slot’ into the mouth and into the throat. Mucus that forms in the trachea is coughed up into the throat. Sometimes birds can be heard to cough or may have a mucus component to their ‘grunt’. Such mucus will sometimes run in a thread from the top of the trachea, which may appear red and inflamed to the roof of the mouth. Dutch veterinarians believe this mucus is associated with mycoplasma

and state that it is very common, affecting 90% of lofts there.

Mycoplasma can be a difficult disease to diagnose in the live bird. Only certain labs culture Mycoplasma, and it can be an expensive procedure. The organism is also fragile and difficult to grow. PCR tests are used to diagnose the condition in chickens. In Australia, the condition is usually diagnosed by suggestive changes found either grossly (white mucus lining the upper 20–30% of the trachea) or microscopically (lymphoid aggregates scattered in increased numbers throughout the respiratory system and increased level of mucus-producing glands in the upper trachea) visible at autopsy. A tentative diagnosis can also be based not only on the signs

shown by the birds, but also by response to treatment.

In the near future it is likely that a definitive diagnosis will be obtained by your vet doing a PCR test, which will look for Mycoplasmal DNA in a sample of throat mucus. Some European veterinarians state that the problem is so common that a loft is assumed to be infected unless it has been treated before racing or recently during racing, and feel that, although it does not clinically affect the birds’ health, it has a big effect on race form. With severe respiratory infections, mucus will accumulate at the beak margins where it becomes air dried and yellow.

When assessing the level of mucus, the birds should not be examined after feeding or exercise as some mucus found normally in the upper crop can, during this time, move into the throat. Similarly, this mucus can be massaged into the throat.

Colour

The lining (mucous membrane) of the throat should be rosy pink in health. It becomes pale with anaemia (low red-blood-cell count) and low blood pressure, which occurs with poor health. With a normal red blood-cell count and blood pressure, the blood vessel at the back of the throat should be turgid and pulsate with the beat of the heart. With respiratory problems, the lining will become pale blue due to the blood not containing enough oxygen.

The tongue, in health, should also be rosy pink. A purple tip can indicate respiratory problems. Some birds, however, have a naturally pigmented tongue tip and so it is a matter of knowing your birds so as not to become confused.

Defects in the tongue outline usually indicate an earlier pigeon pox infection. Yellow plaques on the tongue or throat are usually either a viral vesicle (pox, Circo, PMV or Herpes) or a Trichomonad ulcer. As a general rule, if a line is drawn through the base of the beak, a yellow plaque in front of this will be pox and behind it will be canker. Trichomonads are fragile organisms and the environment from the base of the beak forward is too hostile for them.

Windpipe shape

A bird that is breathing with ease can relax the muscles of the windpipe, making the opening appear narrow and elongated. If the bird is having trouble getting its breath, several mechanisms are available to it to provide more oxygen. One option is to contract the muscles of the windpipe, which will dilate it and give the opening a rounded shape. The healthy pigeon has a glottis (windpipe opening) that is narrow, elongated with sharp edges and with small spicules along the side. The more rounded the glottis, the more distressed the bird. To provide itself with more oxygen the bird can also breathe faster and deeper. This will cause the glottis to move, in the process elevating the tongue tip.

In health, the tongue will lie flat on the floor of the mouth and the glottis will appear still. I am cautious, however, of attaching too much significance to a tongue that is elevated in profile with the beak open, placing more significance on other signs. Respiratory infections, particularly of the air sacs, as well as obesity, egg laying and space-occupying abdominal lesions can all lead to an increased respiratory effort and similar symptoms. The shape of the glottis also varies between families and, as a general rule, cocks have a slightly more ‘slit like’ opening. The ‘slot’ in the roof of the mouth should be free of debris and slightly open. Birds that are breathing with ease should, when in the hand, have their beaks tightly closed. If it is difficult to see whether there is a slight space, the beak can be held closed while monitoring the birds for signs of distress.

Sinuses

As mentioned earlier, within the head of the pigeon are several cavities called sinuses. One of these encircles the eye in the shape of a doughnut. The sinuses interconnect through narrow channels. Some sinuses are poorly drained. With respiratory infection, fluid can accumulate in the sinuses, causing them to bulge, leading to swellings around the eye or over the head.

Swellings around the eye can physically squash the tear duct (which carries tears from the eye to the inside of the choana) causing tears to overflow the eyelid margin and wet the face. When checking for bulges, the head should be looked at not only from the side, but also from the front and top.

and state that it is very common, affecting 90% of lofts there.

Mycoplasma can be a difficult disease to diagnose in the live bird. Only certain labs culture Mycoplasma, and it can be an expensive procedure. The organism is also fragile and difficult to grow. PCR tests are used to diagnose the condition in chickens. In Australia, the condition is usually diagnosed by suggestive changes found either grossly (white mucus lining the upper 20–30% of the trachea) or microscopically (lymphoid aggregates scattered in increased numbers throughout the respiratory system and increased level of mucus-producing glands in the upper trachea) visible at autopsy. A tentative diagnosis can also be based not only on the signs

shown by the birds, but also by response to treatment.

In the near future it is likely that a definitive diagnosis will be obtained by your vet doing a PCR test, which will look for Mycoplasmal DNA in a sample of throat mucus. Some European veterinarians state that the problem is so common that a loft is assumed to be infected unless it has been treated before racing or recently during racing, and feel that, although it does not clinically affect the birds’ health, it has a big effect on race form. With severe respiratory infections, mucus will accumulate at the beak margins where it becomes air dried and yellow.

When assessing the level of mucus, the birds should not be examined after feeding or exercise as some mucus found normally in the upper crop can, during this time, move into the throat. Similarly, this mucus can be massaged into the throat.

Colour

The lining (mucous membrane) of the throat should be rosy pink in health. It becomes pale with anaemia (low red-blood-cell count) and low blood pressure, which occurs with poor health. With a normal red blood-cell count and blood pressure, the blood vessel at the back of the throat should be turgid and pulsate with the beat of the heart. With respiratory problems, the lining will become pale blue due to the blood not containing enough oxygen.

The tongue, in health, should also be rosy pink. A purple tip can indicate respiratory problems. Some birds, however, have a naturally pigmented tongue tip and so it is a matter of knowing your birds so as not to become confused.

Defects in the tongue outline usually indicate an earlier pigeon pox infection. Yellow plaques on the tongue or throat are usually either a viral vesicle (pox, Circo, PMV or Herpes) or a Trichomonad ulcer. As a general rule, if a line is drawn through the base of the beak, a yellow plaque in front of this will be pox and behind it will be canker. Trichomonads are fragile organisms and the environment from the base of the beak forward is too hostile for them.

Windpipe shape

A bird that is breathing with ease can relax the muscles of the windpipe, making the opening appear narrow and elongated. If the bird is having trouble getting its breath, several mechanisms are available to it to provide more oxygen. One option is to contract the muscles of the windpipe, which will dilate it and give the opening a rounded shape. The healthy pigeon has a glottis (windpipe opening) that is narrow, elongated with sharp edges and with small spicules along the side. The more rounded the glottis, the more distressed the bird. To provide itself with more oxygen the bird can also breathe faster and deeper. This will cause the glottis to move, in the process elevating the tongue tip.

In health, the tongue will lie flat on the floor of the mouth and the glottis will appear still. I am cautious, however, of attaching too much significance to a tongue that is elevated in profile with the beak open, placing more significance on other signs. Respiratory infections, particularly of the air sacs, as well as obesity, egg laying and space-occupying abdominal lesions can all lead to an increased respiratory effort and similar symptoms. The shape of the glottis also varies between families and, as a general rule, cocks have a slightly more ‘slit like’ opening. The ‘slot’ in the roof of the mouth should be free of debris and slightly open. Birds that are breathing with ease should, when in the hand, have their beaks tightly closed. If it is difficult to see whether there is a slight space, the beak can be held closed while monitoring the birds for signs of distress.

Sinuses

As mentioned earlier, within the head of the pigeon are several cavities called sinuses. One of these encircles the eye in the shape of a doughnut. The sinuses interconnect through narrow channels. Some sinuses are poorly drained. With respiratory infection, fluid can accumulate in the sinuses, causing them to bulge, leading to swellings around the eye or over the head.

Swellings around the eye can physically squash the tear duct (which carries tears from the eye to the inside of the choana) causing tears to overflow the eyelid margin and wet the face. When checking for bulges, the head should be looked at not only from the side, but also from the front and top.

|

Bird with a sinus infection. Birds have a doughnut-shaped sinus that surrounds the eye. When inflamed, fluid forms in it, which, with gravity, accumulates at its base, causing the section of face below the eye to bulge. This bird also has a concurrent conjunctivitis (inflammation of the membrane that lines the eyelid). Over the next few days, as the inflammatory fluid drains away, the cere will become stained. |

Ceres

Birds produce a white powder which covers the eye and nose ceres. They fail to produce this when sick and so the ceres become dull. In addition, with respiratory infection, they become stained with discharge. Inflammatory material that forms in the sinuses drains underneath the nose cere and then through the ‘slot’ in the roof of the mouth into the back of the throat.

As this material flows under the nose cere, the cere acts like a sponge, absorbing this material, which stains it various shades of brown, depending on the volume of material present. Not all ‘less than white’ ceres, however, indicate a problem. Rain can wash off the white powder covering the cere, exposing the red blood below, to give the cere a pink hue. Also, young hens can lose this white powder through excessive billing. In some lines of bird the ceres are genetically pink (for example, Nuremberg Larks).

Birds produce a white powder which covers the eye and nose ceres. They fail to produce this when sick and so the ceres become dull. In addition, with respiratory infection, they become stained with discharge. Inflammatory material that forms in the sinuses drains underneath the nose cere and then through the ‘slot’ in the roof of the mouth into the back of the throat.

As this material flows under the nose cere, the cere acts like a sponge, absorbing this material, which stains it various shades of brown, depending on the volume of material present. Not all ‘less than white’ ceres, however, indicate a problem. Rain can wash off the white powder covering the cere, exposing the red blood below, to give the cere a pink hue. Also, young hens can lose this white powder through excessive billing. In some lines of bird the ceres are genetically pink (for example, Nuremberg Larks).

|

Long Beak

Some pigeons are born with long beaks and this is normal for them. However when a bird’s beak starts to suddenly increase in length when it is an adult this is usually associated with disease. The visible part of the upper beak is called the rhinotheca. It grows like a human fingernail with the area at the top of the beak gradually moving towards the beak tip. The beak is totally replaced every 3-6 months. Usually the rate of growth matched the rate of wear and so the beak always appears the same length. Abnormally long beaks will develop if there is disease or injury involving the growth area at the base of the beak near the cere or if there is internal disease, particularly involving the liver. Trimming the beak will temporarily help an affected bird prehend its food but the long term answer is to identify and correct the underlying problem so that normal beak growth can again occur. |

Eye

In health, the eye should have a quick blink, a responsive pupil and a rich iris. A bird in which one eye becomes pale usually has a uveitis. The uvea is the iris and its support structures. It floats like a web within the fluid bag that is the eyeball. It loses colour usually in one of two situations:

1. A physical knock to the eye. This causes the uvea to flap within the eyeball, in the process damaging itself.

2. A blood-borne generalised disease, which inflames it. The only diseases in which this occurs with any frequency in pigeons are pigeon pox (including vaccination), some forms of respiratory infection, and Salmonella.

A loss of colour in both eyes usually indicates severe illness. Anaemia, or the drop in blood pressure associated with severe disease, means that there is less blood flowing through the eye, giving it a washed-out appearance.

In health, the eye should have a quick blink, a responsive pupil and a rich iris. A bird in which one eye becomes pale usually has a uveitis. The uvea is the iris and its support structures. It floats like a web within the fluid bag that is the eyeball. It loses colour usually in one of two situations:

1. A physical knock to the eye. This causes the uvea to flap within the eyeball, in the process damaging itself.

2. A blood-borne generalised disease, which inflames it. The only diseases in which this occurs with any frequency in pigeons are pigeon pox (including vaccination), some forms of respiratory infection, and Salmonella.

A loss of colour in both eyes usually indicates severe illness. Anaemia, or the drop in blood pressure associated with severe disease, means that there is less blood flowing through the eye, giving it a washed-out appearance.

Eyelids

Pigeons have, in addition to the two eyelids that we have, a third eyelid (nictitating membrane). All eyelids are lined by a membrane called the conjunctiva. When inflamed, this becomes red and swollen. This inflammation is usually associated with a respiratory infection. With even mild inflammation, the third eyelid can have trouble fitting behind the main eyelids because of the thickened membrane covering it. Severe infection is the classic ‘one eye cold’.

However, not all red watery eyes are associated with respiratory infection. Some older birds, particularly if heavily wattled, develop loose-fitting eyelids, leading to air drying of the conjunctiva and irritation. This is compounded by the bird attempting to relieve the irritation by rubbing the eye with its wing butt.

The eyelids, particularly in pieds, are a site for UV-induced tumours. Goblet cell cysts also occur. Goblet cells produce mucus that enables the tears to stick to the eyeball surface, in the process preventing the eye drying out as the bird flies through wind. A mammal’s eyeball with air passing over it at the speed a pigeon flies would dry out.

In summary

It is surprising, perhaps, just how much information can be gained by a look at the head followed by opening the beak and looking down the throat. Many fanciers seem to do this almost routinely when first handed a bird, and it is important for this not to simply become a habit where important signs are overlooked.

Pigeons have, in addition to the two eyelids that we have, a third eyelid (nictitating membrane). All eyelids are lined by a membrane called the conjunctiva. When inflamed, this becomes red and swollen. This inflammation is usually associated with a respiratory infection. With even mild inflammation, the third eyelid can have trouble fitting behind the main eyelids because of the thickened membrane covering it. Severe infection is the classic ‘one eye cold’.

However, not all red watery eyes are associated with respiratory infection. Some older birds, particularly if heavily wattled, develop loose-fitting eyelids, leading to air drying of the conjunctiva and irritation. This is compounded by the bird attempting to relieve the irritation by rubbing the eye with its wing butt.

The eyelids, particularly in pieds, are a site for UV-induced tumours. Goblet cell cysts also occur. Goblet cells produce mucus that enables the tears to stick to the eyeball surface, in the process preventing the eye drying out as the bird flies through wind. A mammal’s eyeball with air passing over it at the speed a pigeon flies would dry out.

In summary

It is surprising, perhaps, just how much information can be gained by a look at the head followed by opening the beak and looking down the throat. Many fanciers seem to do this almost routinely when first handed a bird, and it is important for this not to simply become a habit where important signs are overlooked.