- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

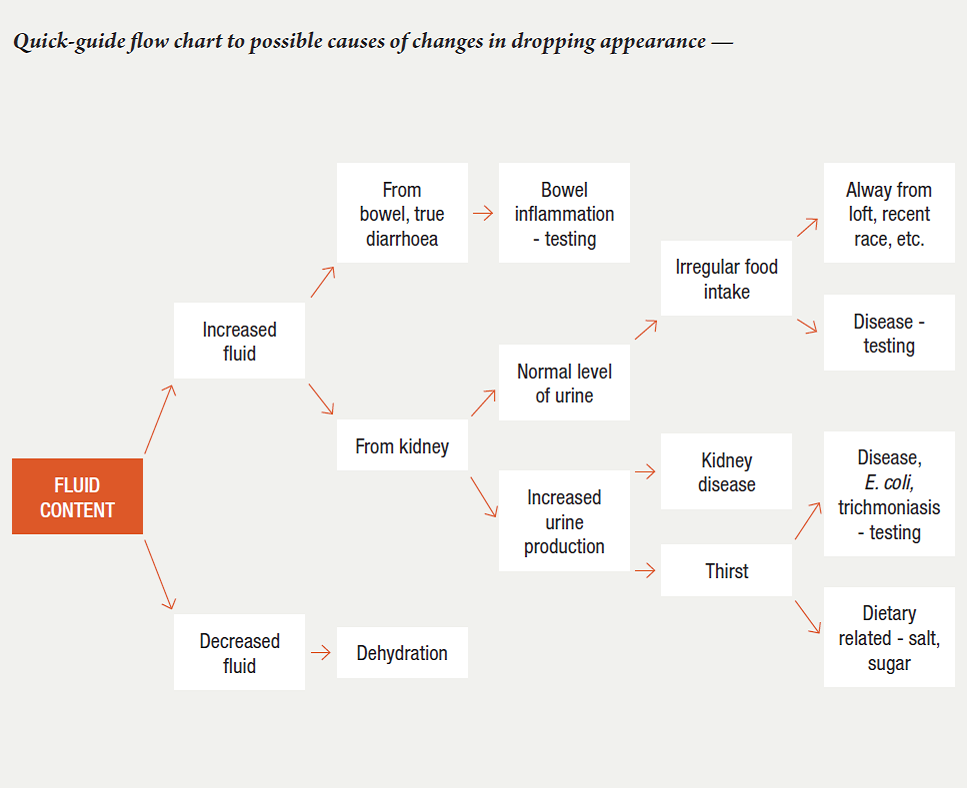

For fanciers, often the first indication that a problem is present in their birds is a change in their droppings. All birds, including pigeons, are able to mask health problems quite well. In the wild, the bird that looks sick is the one targeted by predators. There has been strong evolutionary pressure, therefore, for a bird to be able to hide the fact that it is sick. Often birds only start to look sick once illness has progressed to the stage where the bird can no longer mask their ill health. This allows a problem to progress well into the stage where it can affect race form, with the pigeons still handling normally and looking reasonable and yet having health problems present. However, often with only subtle health changes, the droppings will change. Even if the droppings of only a few birds are affected, they should be investigated as these are often from the first birds ‘breaking down’ and may represent the ‘tip of the ice berg’, with some problems going on to affect the team and the birds’ form as a whole.

Most pigeon racers like to clean their pigeon loft each morning. In doing so, they are confronted by one of the best means by which to assess the health of their birds – the droppings. By examining the droppings, the fancier can gather information regarding his birds’ appetite, hydration status and gastrointestinal, liver and kidney function. By testing the droppings, the pigeon veterinarian can gather further information.

Before being able to interpret the appearance of the droppings, it is important to understand what is normal. Inside the vent of the pigeon is a structure called the cloaca. This is a bag-like structure divided into three compartments. Into this bag empties the bowel, the two ureters (tubes that bring waste from the kidneys) and either the oviduct leading from the ovary in the hen, or the two vas deferens leading from the testes in the male. Ducts from the liver and pancreas open into the bowel. The appearance of the dropping reflects the function of all of these structures. The pigeon relaxes the vent to allow the contents of the cloaca to empty.

Most pigeon racers like to clean their pigeon loft each morning. In doing so, they are confronted by one of the best means by which to assess the health of their birds – the droppings. By examining the droppings, the fancier can gather information regarding his birds’ appetite, hydration status and gastrointestinal, liver and kidney function. By testing the droppings, the pigeon veterinarian can gather further information.

Before being able to interpret the appearance of the droppings, it is important to understand what is normal. Inside the vent of the pigeon is a structure called the cloaca. This is a bag-like structure divided into three compartments. Into this bag empties the bowel, the two ureters (tubes that bring waste from the kidneys) and either the oviduct leading from the ovary in the hen, or the two vas deferens leading from the testes in the male. Ducts from the liver and pancreas open into the bowel. The appearance of the dropping reflects the function of all of these structures. The pigeon relaxes the vent to allow the contents of the cloaca to empty.

Analysis of organ function

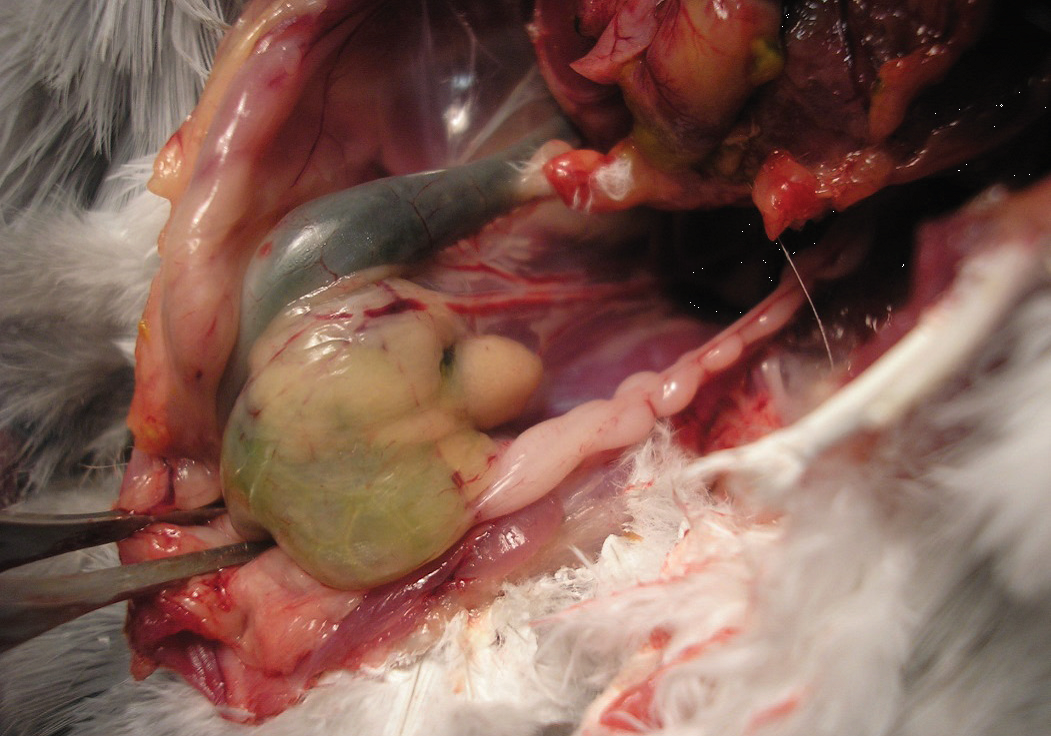

The kidney

The kidney has two main functions: to maintain normal fluid balance in the body and to excrete the body’s ammonia-based metabolites. In birds, there are two ammonia-based metabolites – urea and uric acid. The avian kidney is an amazing structure in that it has two types of filtration units, each producing their own type of urine. One is like that of a mammal and the other is similar to that of a reptile. The mammal type has three components (a glomerulus, renal tubule and Loop of Henle). Here the body’s urea is excreted actively in solution along with about 20% of the uric acid.

For this process to occur normally, the bird needs to be well hydrated and the kidney needs to be healthy and perfused with blood. The reptile type of filtration unit lacks the Loop of Henle. It is here that about 80% of the uric acid is excreted. This process occurs passively and only starts to fail with advanced dehydration or advanced primary disease of the kidney. If these processes fail, then the levels of uric acid and urea start to increase in the blood stream.

The kidney

The kidney has two main functions: to maintain normal fluid balance in the body and to excrete the body’s ammonia-based metabolites. In birds, there are two ammonia-based metabolites – urea and uric acid. The avian kidney is an amazing structure in that it has two types of filtration units, each producing their own type of urine. One is like that of a mammal and the other is similar to that of a reptile. The mammal type has three components (a glomerulus, renal tubule and Loop of Henle). Here the body’s urea is excreted actively in solution along with about 20% of the uric acid.

For this process to occur normally, the bird needs to be well hydrated and the kidney needs to be healthy and perfused with blood. The reptile type of filtration unit lacks the Loop of Henle. It is here that about 80% of the uric acid is excreted. This process occurs passively and only starts to fail with advanced dehydration or advanced primary disease of the kidney. If these processes fail, then the levels of uric acid and urea start to increase in the blood stream.

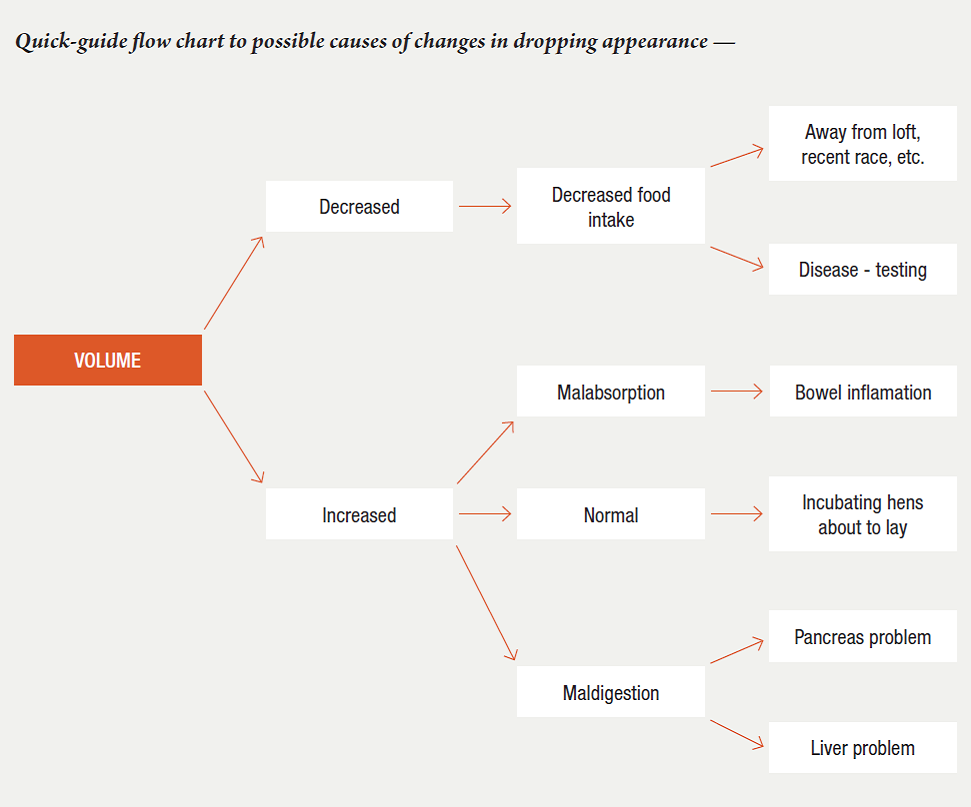

In health, pigeons, therefore, produce two types of urine:

1. Solid urine – white uric acid crystals. Uric acid forms in the reptile filtration units in the kidneys and is excreted as a thick white paste. This makes up the typical white cap of the dropping.

2. Liquid urine – fluid with urea and some uric acid dissolved in it from the mammalian filtration units in the kidney. This is a clear liquid and is usually not visible in the dropping if the pigeon has been eating and drinking normally. Apart from urine, droppings contain digested food coming down from the large bowel. Usually the liquid urine is absorbed by this digested food and is not visible.

Liquid urine becomes more visible in the droppings in four situations:

1. Reduced food intake in a normally hydrated bird. If the bird has access to water and is drinking normally, urine production will be relatively constant. If, however, the bird has not eaten recently, then the physical volume of digested food in the dropping will decrease. This means that there will be less to absorb the liquid urine, making the urine more obvious. This gives the dropping the appearance of having a liquid ring around a central amount of digested food. This is most commonly seen when pigeons are due for a feed. Fanciers will sometimes call the clinic saying that after training there are a lot of wet patches on the loft floor. This is probably normal; the birds are hungry and due for a feed. Usually within two to three hours of being fed, digested food starts appearing in the droppings, this absorbs (and conceals) the urine and the droppings’ appearance becomes more normal.

2. The pigeons are drinking more. Recently weaned youngsters and hens at the time of laying will normally drink more. A thirst, however, can be created by a dietary component such as an excessive intake of salt or sugar, perhaps from pick stones and grits with salt, or sugar-based medication. Salt and sugar can only be passed from the body at a particular concentration. If these are high in the diet then, as they are passed, a lot of fluid in the form of urine is produced. Some diseases can also make the birds thirsty. Two of the common ones are wet canker and Chlamydia infection. The Trichomonad organisms that cause canker release toxins into the body that can damage the liver and kidneys. A thirst is created and the birds drink more, leading to an increase in urine production This is one of the reasons wet canker is called wet canker – because when infected the birds produce wet droppings. Chlamydia has a particular protein called MOMP (major outer membrane protein) on its surface that specifically damages the kidney, compromising its ability to concentrate urine. This again leads to a lot of dilute urine being produced. Less commonly a thirst can develop with liver disease, pancreatic disease and Type2 diabetes.

3. Disease of the kidneys. If the kidneys’ function is compromised, they lose the ability to:

a. Excrete ammonia-based waste. This then starts to accumulate in the blood, making the birds very sick. These elevations can be detected in the blood once established along with other changes in both haematology and biochemistry blood tests.

b. Concentrate urine. As kidneys fail, they lose the ability to concentrate urine, leading to the production of large amounts of dilute urine. The pigeon can compensate for this by drinking more. Birds with kidney disease that are deprived of water quickly become dehydrated Common causes of primary kidney diseases include: i. Nutritional problems – for example, too much calcium, too much vitamin D, not enough vitamin A, too high protein, omega 3/omega 6 fatty acid imbalance. Often seen if pellets made for other species such as chickens are fed to pigeons.

Common causes of primary kidney diseases include:

i. Nutritional problems – for example, too much calcium, too much vitamin D, not enough vitamin A, too high protein, omega3/ omega 6 fatty acid imbalance. Often seen if pellets made for other species such as chickens are fed to pigeons.

ii. Heavy metal toxicity – seen where galvanised drinkers are used or copper sulfate is used to treat canker. Lead, zinc, copper and aluminium are all common toxins. Heavy metal poisoning can occur in clinical and subclinical states. Low-grade poisonings, e.g. from drinkers with galvanised solder, may not be significant enough to result in obvious clinical signs or death but can still result in significant kidney damage. This damage is often permanent.

iii. Infection – due to bacteria or Chlamydia. Any systemic infection can cause kidney damage. Bacterial septicaemias and toxaemias, where there are bacteria or bacterial toxins circulating through the blood stream, can both result in kidney damage. Even when the primary infection is treated, some permanent renal damage can result.

iv. Medications – for example, doxycycline in overdose.

v. Mycotoxins – these are toxins produced by fungi that are then ingested by the birds. These toxins grow in moist grains and legumes. They can occur on the grain prior to harvest under wet conditions or after harvest if the grain is stored moist or becomes wet. Birds can die of acute kidney failure if ingested toxin levels are high, but most commonly chronic subclinical damage occurs.

vi. Dehydration – any cause of dehydration can have a dramatic effect on the kidneys. Periods without water during transport or racing causing reduced water intake result in renal damage. Although a bird survives the initial episode, subclinical renal damage can occur.

vii. Myoglobinurea – when pigeons are exercised beyond their fitness capability, muscle protein can break down. Various metabolites are then excreted through the kidneys, damaging them in the process.

1. Solid urine – white uric acid crystals. Uric acid forms in the reptile filtration units in the kidneys and is excreted as a thick white paste. This makes up the typical white cap of the dropping.

2. Liquid urine – fluid with urea and some uric acid dissolved in it from the mammalian filtration units in the kidney. This is a clear liquid and is usually not visible in the dropping if the pigeon has been eating and drinking normally. Apart from urine, droppings contain digested food coming down from the large bowel. Usually the liquid urine is absorbed by this digested food and is not visible.

Liquid urine becomes more visible in the droppings in four situations:

1. Reduced food intake in a normally hydrated bird. If the bird has access to water and is drinking normally, urine production will be relatively constant. If, however, the bird has not eaten recently, then the physical volume of digested food in the dropping will decrease. This means that there will be less to absorb the liquid urine, making the urine more obvious. This gives the dropping the appearance of having a liquid ring around a central amount of digested food. This is most commonly seen when pigeons are due for a feed. Fanciers will sometimes call the clinic saying that after training there are a lot of wet patches on the loft floor. This is probably normal; the birds are hungry and due for a feed. Usually within two to three hours of being fed, digested food starts appearing in the droppings, this absorbs (and conceals) the urine and the droppings’ appearance becomes more normal.

2. The pigeons are drinking more. Recently weaned youngsters and hens at the time of laying will normally drink more. A thirst, however, can be created by a dietary component such as an excessive intake of salt or sugar, perhaps from pick stones and grits with salt, or sugar-based medication. Salt and sugar can only be passed from the body at a particular concentration. If these are high in the diet then, as they are passed, a lot of fluid in the form of urine is produced. Some diseases can also make the birds thirsty. Two of the common ones are wet canker and Chlamydia infection. The Trichomonad organisms that cause canker release toxins into the body that can damage the liver and kidneys. A thirst is created and the birds drink more, leading to an increase in urine production This is one of the reasons wet canker is called wet canker – because when infected the birds produce wet droppings. Chlamydia has a particular protein called MOMP (major outer membrane protein) on its surface that specifically damages the kidney, compromising its ability to concentrate urine. This again leads to a lot of dilute urine being produced. Less commonly a thirst can develop with liver disease, pancreatic disease and Type2 diabetes.

3. Disease of the kidneys. If the kidneys’ function is compromised, they lose the ability to:

a. Excrete ammonia-based waste. This then starts to accumulate in the blood, making the birds very sick. These elevations can be detected in the blood once established along with other changes in both haematology and biochemistry blood tests.

b. Concentrate urine. As kidneys fail, they lose the ability to concentrate urine, leading to the production of large amounts of dilute urine. The pigeon can compensate for this by drinking more. Birds with kidney disease that are deprived of water quickly become dehydrated Common causes of primary kidney diseases include: i. Nutritional problems – for example, too much calcium, too much vitamin D, not enough vitamin A, too high protein, omega 3/omega 6 fatty acid imbalance. Often seen if pellets made for other species such as chickens are fed to pigeons.

Common causes of primary kidney diseases include:

i. Nutritional problems – for example, too much calcium, too much vitamin D, not enough vitamin A, too high protein, omega3/ omega 6 fatty acid imbalance. Often seen if pellets made for other species such as chickens are fed to pigeons.

ii. Heavy metal toxicity – seen where galvanised drinkers are used or copper sulfate is used to treat canker. Lead, zinc, copper and aluminium are all common toxins. Heavy metal poisoning can occur in clinical and subclinical states. Low-grade poisonings, e.g. from drinkers with galvanised solder, may not be significant enough to result in obvious clinical signs or death but can still result in significant kidney damage. This damage is often permanent.

iii. Infection – due to bacteria or Chlamydia. Any systemic infection can cause kidney damage. Bacterial septicaemias and toxaemias, where there are bacteria or bacterial toxins circulating through the blood stream, can both result in kidney damage. Even when the primary infection is treated, some permanent renal damage can result.

iv. Medications – for example, doxycycline in overdose.

v. Mycotoxins – these are toxins produced by fungi that are then ingested by the birds. These toxins grow in moist grains and legumes. They can occur on the grain prior to harvest under wet conditions or after harvest if the grain is stored moist or becomes wet. Birds can die of acute kidney failure if ingested toxin levels are high, but most commonly chronic subclinical damage occurs.

vi. Dehydration – any cause of dehydration can have a dramatic effect on the kidneys. Periods without water during transport or racing causing reduced water intake result in renal damage. Although a bird survives the initial episode, subclinical renal damage can occur.

vii. Myoglobinurea – when pigeons are exercised beyond their fitness capability, muscle protein can break down. Various metabolites are then excreted through the kidneys, damaging them in the process.

Not diarrhoea, but rather polyuria (a large amount of dilute urine) giving the dropping a watery appearance.

Not diarrhoea, but rather polyuria (a large amount of dilute urine) giving the dropping a watery appearance.

4. Stress. Birds, unlike us, can modify the concentration of their urine after it leaves the kidneys. In mammals, urine passes directly from the kidneys to the urinary bladder and remains unaltered until voided. Birds do not have a bladder. Urine passes from the kidneys into the cloaca. Once in the cloaca, the urine can be modified. Fluid can be reabsorbed back into the body through the cloacal wall. Material can also move from the cloaca back into the lower bowel, where fluid can also be resorbed. A relaxed pigeon empties its cloaca once the process is complete. Presumably, a full cloaca at the end of this process starts to become uncomfortable. The pigeon then relaxes the cloacal opening (the vent) and a dropping is passed. The process can be interrupted at any time. If frightened or excited, the pigeon will often jettison its cloacal contents before the reabsorption process is complete, leading to a pool of clear urine with a firm tube of bowel content floating in it (the so-called ‘snake’ dropping).

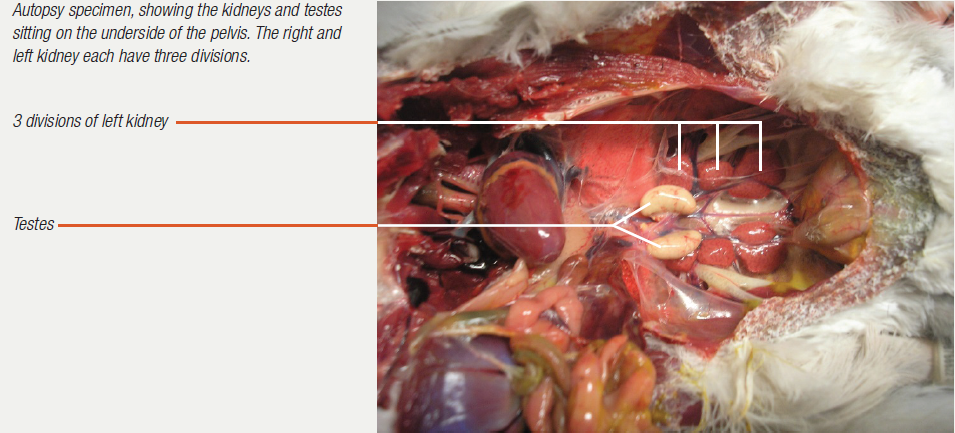

Problems in the kidneys can also be reflected in the urates (the solid white urine). Changes in the colour, consistency and volume are all indicators of health. Volume will increase with impaired kidney function, if birds are fed a high-protein diet (for example, pea- or bean-based) or in starvation, when the pigeon is breaking down its own body tissue protein. Viscosity will increase if the bird is becoming dehydrated.

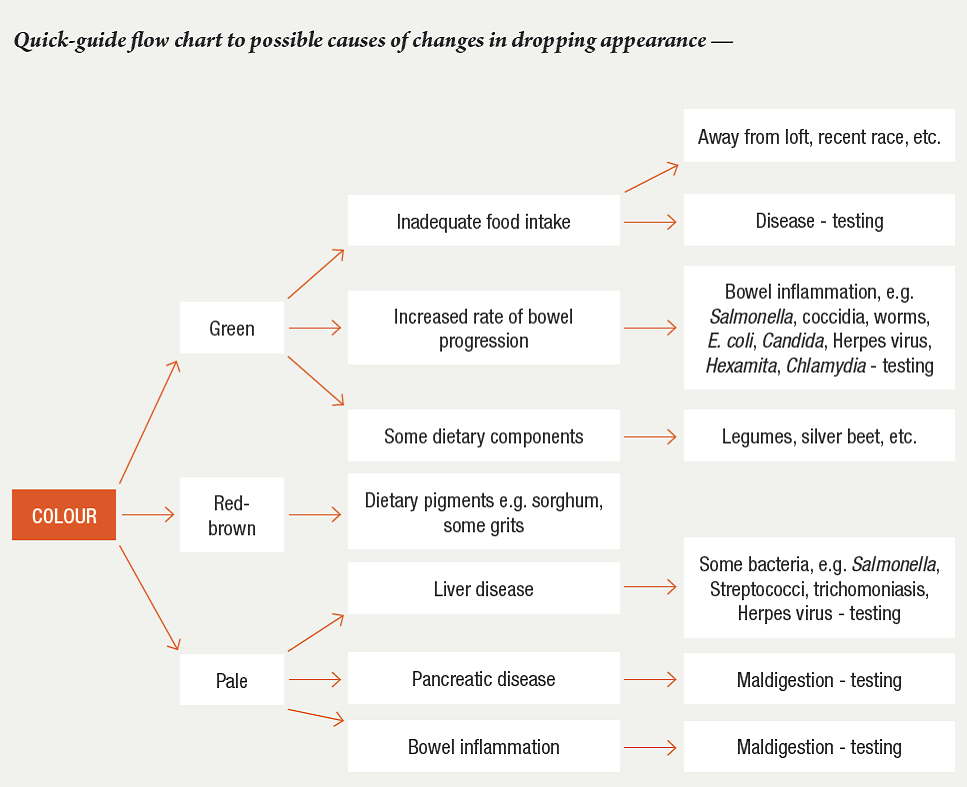

The normally white cap of the dropping can become green in liver disease (due to a bile breakdown product accumulating in the blood and being passed through the kidneys as a substance called biliverdin, which is green), bright yellow with vitamin B supplementation, dull yellow with starvation, and red-brown with kidney disease. If the problem is becoming a flock one, or if an individual bird of value is affected, an avian veterinarian can check the urine for sugar, blood, protein, pH and specific gravity, and analyse its sediment, which may contain red or white blood cells, epithelial cells, crystals, bacteria, yeasts, fungi, sperm or kidney casts.

The normally white cap of the dropping can become green in liver disease (due to a bile breakdown product accumulating in the blood and being passed through the kidneys as a substance called biliverdin, which is green), bright yellow with vitamin B supplementation, dull yellow with starvation, and red-brown with kidney disease. If the problem is becoming a flock one, or if an individual bird of value is affected, an avian veterinarian can check the urine for sugar, blood, protein, pH and specific gravity, and analyse its sediment, which may contain red or white blood cells, epithelial cells, crystals, bacteria, yeasts, fungi, sperm or kidney casts.

The liver

The liver opens via a duct (called the bile duct) into the upper bowel. It produces an enzyme called bile, which travels along this duct into the bowel. Bile is bright green in pigeons and digests dietary fat. This process is affected by what the pigeon is eating and when the pigeon eats, but goes on to some extent all the time. As the faeces move down the bowel and digestion is completed, most of the bile is reabsorbed back through the bowel wall into the blood stream. What is left of the bright green bile becomes non-visible as the bile is absorbed by the other components of the dropping. Droppings will become bright green if:

1. The bowel wall is irritated (leading to hyper-motility and a decreased opportunity to reabsorb bile) or inflamed (interfering directly with the bowel’s ability to reabsorb the bile). This situation is seen with coccidia, E. coli Adeno virus and other infections.

2. If the pigeon has a reduced food intake, either through being away from the loft and not eating, or because of disease.

Either process leads to relative more bile being present in the droppings when they are passed. The dropping then takes on the colour of the bright green bile.

Bright green droppings, therefore, mean that either the pigeon has a problem with its bowel or is not eating properly. If food is available, it is probably not eating because it is sick.

The liver opens via a duct (called the bile duct) into the upper bowel. It produces an enzyme called bile, which travels along this duct into the bowel. Bile is bright green in pigeons and digests dietary fat. This process is affected by what the pigeon is eating and when the pigeon eats, but goes on to some extent all the time. As the faeces move down the bowel and digestion is completed, most of the bile is reabsorbed back through the bowel wall into the blood stream. What is left of the bright green bile becomes non-visible as the bile is absorbed by the other components of the dropping. Droppings will become bright green if:

1. The bowel wall is irritated (leading to hyper-motility and a decreased opportunity to reabsorb bile) or inflamed (interfering directly with the bowel’s ability to reabsorb the bile). This situation is seen with coccidia, E. coli Adeno virus and other infections.

2. If the pigeon has a reduced food intake, either through being away from the loft and not eating, or because of disease.

Either process leads to relative more bile being present in the droppings when they are passed. The dropping then takes on the colour of the bright green bile.

Bright green droppings, therefore, mean that either the pigeon has a problem with its bowel or is not eating properly. If food is available, it is probably not eating because it is sick.

As mentioned above, most bile is reabsorbed back through the bowel wall into the bloodstream as digestion is completed. The blood stream then takes the bile back to the liver, where it is available for reuse. In this way, a cycle is created with bile travelling down the bile duct into the bowel. From here it travels back to the liver via the blood stream before going down the bile duct again. If the liver is diseased, this process breaks down. The liver cannot pick up the bile from the blood stream. This bile in the blood is eventually excreted from the body through the kidneys as a bile breakdown product called biliverdin. This stains the uric acid (white cap) component of the dropping a green colour.

Occasionally, with advanced liver disease, less bile will be produced in the liver and ‘bile stasis’ will occur within the liver. Less bile moves down the bile duct, food can’t be properly digested and the droppings become pale.

Common causes of liver disease in pigeons include bacteria such as Salmonella and Streptococci, as well as canker (the Trichomonads gain access via the bile duct from the bowel), Chlamydia and Herpes virus. Because the liver in the body’s filter, it is vulnerable to damage by toxins. The most common toxins experienced by pigeons are fungal toxins.

One of the liver’s jobs is to remove old and damaged red blood cells from the circulation. Some of their components become part of the bile. If red-blood-cell breakdown is excessive, even a healthy liver cannot cope with this increased work load and breakdown products will be excreted through the kidneys, giving the urates a red-brown colour. In Victoria, the usual cause of red-blood-cell damage is, in fact, injury to the pigeon due to attack by a hawk or hitting a wire, etc. However, in other countries, pigeon malaria, caused by a parasite called Haemoproteus, which lives within and damages the red blood cell, should be considered.

Occasionally, with advanced liver disease, less bile will be produced in the liver and ‘bile stasis’ will occur within the liver. Less bile moves down the bile duct, food can’t be properly digested and the droppings become pale.

Common causes of liver disease in pigeons include bacteria such as Salmonella and Streptococci, as well as canker (the Trichomonads gain access via the bile duct from the bowel), Chlamydia and Herpes virus. Because the liver in the body’s filter, it is vulnerable to damage by toxins. The most common toxins experienced by pigeons are fungal toxins.

One of the liver’s jobs is to remove old and damaged red blood cells from the circulation. Some of their components become part of the bile. If red-blood-cell breakdown is excessive, even a healthy liver cannot cope with this increased work load and breakdown products will be excreted through the kidneys, giving the urates a red-brown colour. In Victoria, the usual cause of red-blood-cell damage is, in fact, injury to the pigeon due to attack by a hawk or hitting a wire, etc. However, in other countries, pigeon malaria, caused by a parasite called Haemoproteus, which lives within and damages the red blood cell, should be considered.

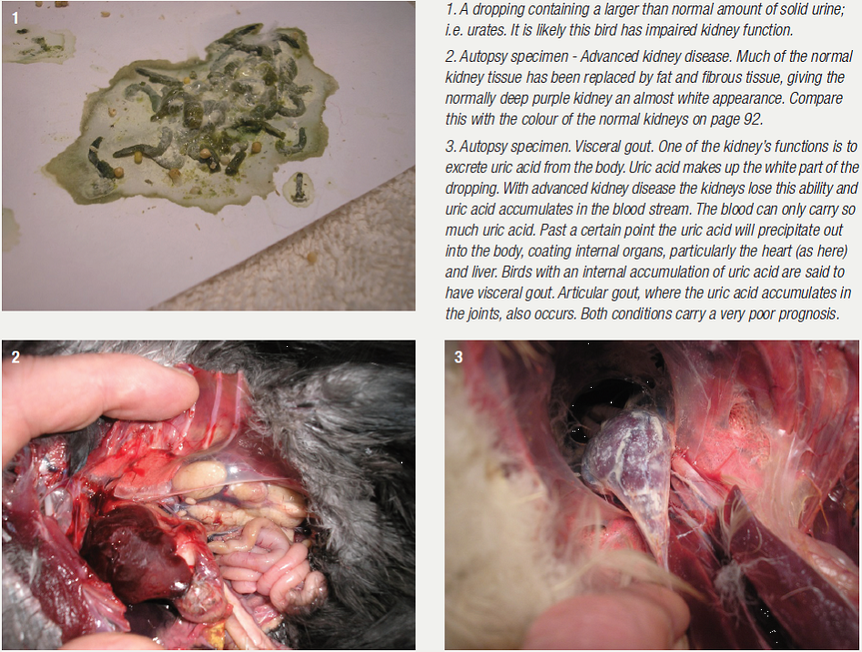

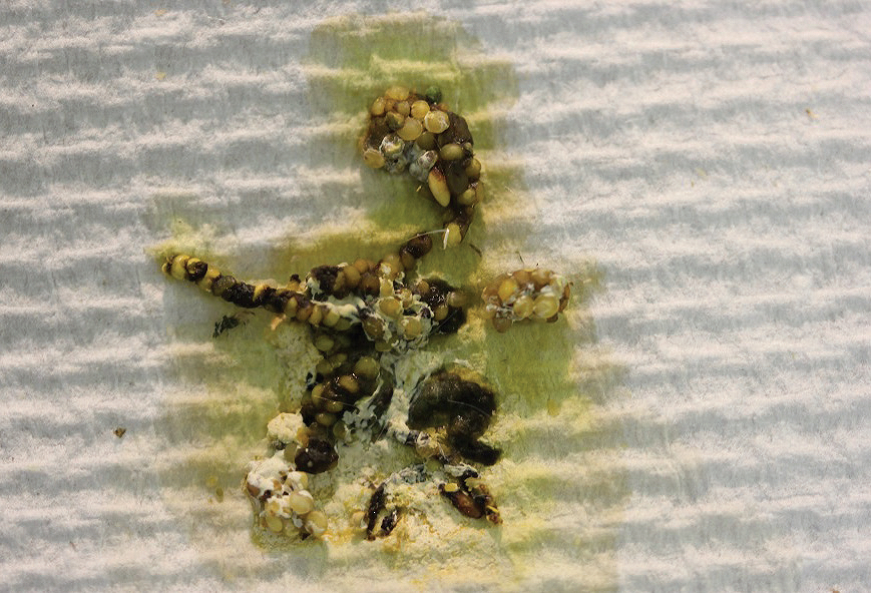

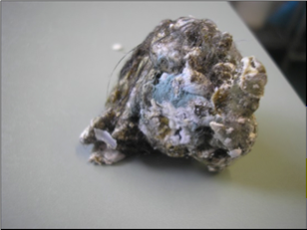

Popcorn poos’, due to pancreatic insufficiency leading to maldigestion.

Popcorn poos’, due to pancreatic insufficiency leading to maldigestion.

The pancreas

Like the liver, the pancreas also has a duct that drains into the upper bowel. It produces several enzymes, including lipase and amylase, that digest fats and sugars in the food. Occasionally, in individual birds, the pancreas will fail to produce sufficient levels of these enzymes. This means that the bird cannot digest its food properly. As a result, the droppings are large and pale, and under the microscope a lot of undigested material is visible. Such droppings are sometimes called ‘popcorn poos’, as a consequence of their appearance. Problems in the pancreas are uncommon, but the appearance of the droppings can be mistakenly confused with bowel or liver problems. Blood tests or more reliably, a pancreatic biopsy, can confirm the diagnosis.

Like the liver, the pancreas also has a duct that drains into the upper bowel. It produces several enzymes, including lipase and amylase, that digest fats and sugars in the food. Occasionally, in individual birds, the pancreas will fail to produce sufficient levels of these enzymes. This means that the bird cannot digest its food properly. As a result, the droppings are large and pale, and under the microscope a lot of undigested material is visible. Such droppings are sometimes called ‘popcorn poos’, as a consequence of their appearance. Problems in the pancreas are uncommon, but the appearance of the droppings can be mistakenly confused with bowel or liver problems. Blood tests or more reliably, a pancreatic biopsy, can confirm the diagnosis.

The intestine

The intestine is a muscular tube that pushes food along its length. It is lined by cells that absorb fluid and nutrition into the body. If the bowel lining is inflamed, the rate of progression of food is increased and the bowel’s ability to absorb fluids is decreased. These both result in a watery, poorly digested dropping arriving at the cloaca. This is true diarrhoea, and it is important for the fancier not to confuse this with a liquid urine dropping as discussed above.

The increased rate of passage can also affect the colour of the faeces. As mentioned above, bile pigments may have inadequate time to be reabsorbed or mixed with the rest of the dropping, giving the dropping a greenish colour. Diarrhoea, however, is not always green, as malabsorption of other faecal components has an effect.

The intestine is a muscular tube that pushes food along its length. It is lined by cells that absorb fluid and nutrition into the body. If the bowel lining is inflamed, the rate of progression of food is increased and the bowel’s ability to absorb fluids is decreased. These both result in a watery, poorly digested dropping arriving at the cloaca. This is true diarrhoea, and it is important for the fancier not to confuse this with a liquid urine dropping as discussed above.

The increased rate of passage can also affect the colour of the faeces. As mentioned above, bile pigments may have inadequate time to be reabsorbed or mixed with the rest of the dropping, giving the dropping a greenish colour. Diarrhoea, however, is not always green, as malabsorption of other faecal components has an effect.

Bowel problems are common in pigeons, and dropping analysis is a useful and often-used diagnostic tool. Common tests include a faecal flotation test, where a measured volume of dropping is placed into a specific gravity medium and disease organisms, with time, separate and rise to the surface. This is then aspirated and prepared as a microscopic slide. This test is used to check for worms, coccidia, and ‘thrush’.

Another test, called a wet smear, involves smearing a fresh sample of dropping across a microscope slide with saline. Subsequent examination may reveal protozoans, such as Hexamita, or bacteria. Faecal smears can also be stained specifically to reveal bacteria. These bacteria can also be cultured and then tested against a number of antibiotics to see which one is best at killing them.

Chlamydia is a common cause of respiratory and bowel infection in pigeons. When these organisms increase in number, they can be shed through the bowel wall and can sometimes be identified in the droppings with specific tests.

Another test, called a wet smear, involves smearing a fresh sample of dropping across a microscope slide with saline. Subsequent examination may reveal protozoans, such as Hexamita, or bacteria. Faecal smears can also be stained specifically to reveal bacteria. These bacteria can also be cultured and then tested against a number of antibiotics to see which one is best at killing them.

Chlamydia is a common cause of respiratory and bowel infection in pigeons. When these organisms increase in number, they can be shed through the bowel wall and can sometimes be identified in the droppings with specific tests.

Many pigments in the grain and grits of a pigeon’s diet will pass unaltered through the bowel, so that birds eating a lot of legumes, such as peas, may have slightly green droppings, while grain with a high tannin content, such as sorghum, will cause the droppings to be more red-brown. When the bowel is inflamed, increased speed of passage of the food leads to less digestion and absorption, and so these colours can be more marked. Food that is not digested due to general ill health or inflammation or infection in the bowel can ferment, with resultant gas formation giving the diarrhoea a bubbly appearance.

The stomach

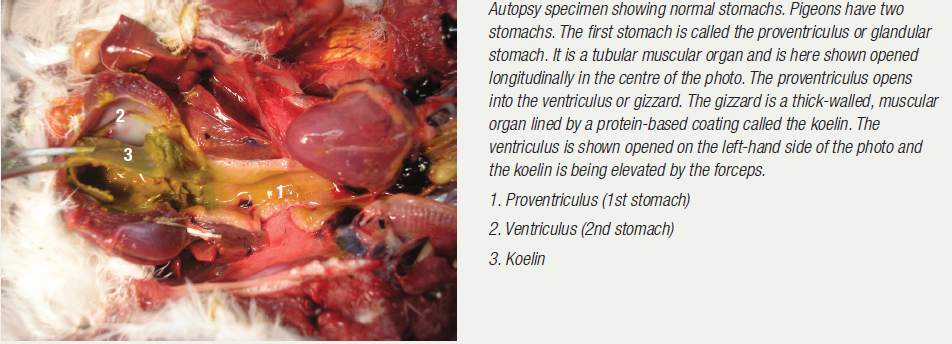

Pigeons have two stomachs. In the first, which is called the proventriculus or glandular stomach, digestive

enzymes such as pepsinogen and acids are mixed with the food. The first stomach opens into the second

through a narrow isthmus.

Pigeons have two stomachs. In the first, which is called the proventriculus or glandular stomach, digestive

enzymes such as pepsinogen and acids are mixed with the food. The first stomach opens into the second

through a narrow isthmus.

The second stomach is called the ventriculus or gizzard. Here, the pigeon keeps a supply of digestive stones that, together with the gizzard’s thick muscular wall, act like mill stones, grinding the seed to a pulp. Disease in this area leads to hyper-motility and increased rate of passage. With the grain moving through this area too quickly, normal digestion cannot occur, leading to the passing of whole grain in the droppings. Infections due to bacteria and yeasts can occur in the stomach and in older birds the stomach can be a site of cancer.

Passage of whole grain in the droppings indicates hypermotility of the proventriculus/ventriculus area. Infection or inflammation in the proventriculus or ventriculus leads to an increased rate of passage, and malfunctioning of the normal digestive processes that should occur here. This results in the passing of whole grain in the droppings.

In health

In pigeons that are healthy, the dropping will usually be a shade of green-brown to brown, maintain the shape of the cloaca after being passed, and topped by a cap of white urates with the liquid urine being invisible. The analogy of a small, snow-capped mountain is apt. Ideally, the droppings should be uniform throughout the loft. Now, with an understanding of the physiological processes that can affect the dropping, how can the fancier interpret changes in his birds’ droppings throughout the racing season?

Dropping interpretation in the race season – problem solving

As mentioned above, one good way of monitoring the birds’ health is by observing their droppings. As most fanciers clean their racing loft each day, simply observing the droppings during the cleaning process is a good way of monitoring the birds’ health over the previous 24 hours. Many problems that affect race performance are subclinical. This means that race form is affected before the birds actually start to look sick to the fancier. As changes in the dropping usually occur one or two days before an unwell bird starts to look sick to us, observing and effectively managing the abnormal changes in droppings does much to head off a downward turn in form.

In summary

As outlined above, essentially the bowel is a hollow tube into which several organs, in particular the liver, empty via ducts. The bowel terminates in the cloaca (a bag just inside the bird’s external opening). Ducts leading from the kidney also terminate here and deposit the bird’s urinary waste. Birds produce two sorts of urine, liquid urine, which looks like clear water, and also solid urine made up of a white paste of uric acid crystals. In the cloaca, the undigested remnants of food from the bowel, liquid and solid urine from the kidney, and a number of normal discharges, notably bile from the liver and mucus from the bowel wall, all accumulate. Once in the cloaca, some fluid is resorbed until, in health, a firm dropping, normally of a brownish colour, is produced. When the cloaca is uncomfortably full, the bird relaxes the cloacal opening and passes a dropping. The changes in droppings that should alert the fancier to a health problem are when droppings become green, or watery, or both.

Watery droppings – problem solving

Watery droppings usually occur in one of two situations:

1. True diarrhoea, due to bowel disease interfering with the absorption of fluid. Possibilities include infectious problems such as worms, coccidia, ‘thrush’ or a bacterial infection, while the most likely non-infectious causes are ingestion of either irritant or toxic substances, either while free-lofting or associated with a change of diet. Usually an infectious cause can be detected quickly by microscopic examination of a faecal smear.

2. Where the liquid urine component of the dropping is visible, due to:

a. Premature cloacal emptying. This can occur at any time if the birds are frightened or excited. It is good to check for this in the morning to see if the birds have rested well in the loft through the night. Race birds pass most of their droppings through the night. If the fancier finds tight, nut-like droppings on the perches in the mornings, it means that the birds have had an uninterrupted night’s sleep. Conversely, loose morning droppings that improve through the day indicate a disturbed night. A poor night’s sleep inhibits the development of race form and can be caused by things as diverse as:

• external parasites

• diseases such as respiratory infection (which causes sneezing) and E. coli (which causes ‘gut ache’)

• mice, noise and light around the loft

• an uncomfortable loft environment; e.g. draughts, a cold loft, or high humidity.

These loose droppings, although not a direct health problem, do indicate the birds are not resting properly and, as we know, inadequate rest is a stress on the birds, which increases their vulnerability to health problems. To maintain race form, the birds must rest well through the night.

b. The birds are overdue for feeding. This is most commonly observed after the morning exercise. At this time the birds have not been fed so there is virtually no digested food in the dropping. Provided the birds are not dehydrated, urine production is constant. The birds often empty their cloaca on landing. The result is a small amount of green-brown material (mainly bile and bowel mucus), surrounded by a ring of clear water. So a watery dropping in the morning prior to feeding, and particularly after exercise, is usually quite normal. A better time to assess the dropping is after feeding and a period of rest. As digested food starts to appear in the cloaca several hours after feeding, it acts like a sponge, mopping up the urine.

In both of the above situations, the result is a healthy dropping from a healthy bird, but because the dropping is watery it can concern the fancier.

c. Excessive urine production due to a thirst. During racing the most common diseases to consider are wet canker (due to toxin release making the bird thirsty), Chlamydia (due to MOMP), or Mycoplasmal airsaculitis (inflamed air sacs are less efficient at water regulation). Consider also the use of excessively salty or sugary medications (e.g. Epsom salts), grits or pick stones, which either create a thirst or can actually cause fluid to move out of the body into the bowel space.

d. Primary kidney disease. If wet droppings are persistent and many birds are affected, this warrants significant investigation.

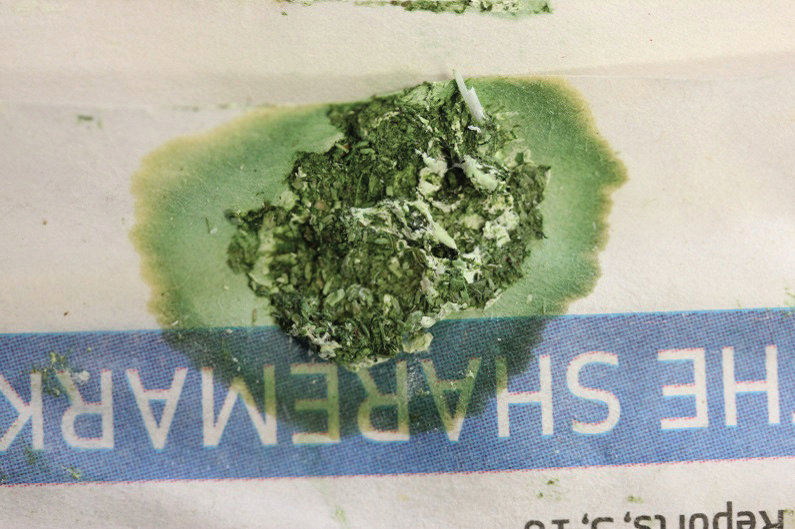

Green droppings – problem solving

Green droppings may or may not be associated with disease. Green droppings may occur in association with:

1. Dietary components. The main factor affecting the colour of a pigeon’s dropping is what it has eaten. Pigeons digest many of the pigments found in their food rather poorly and so these pass relatively unaltered through the system and colour the dropping. For example, birds eating a lot of pink minerals can be expected to have brownish droppings. Pigeons digest the green pigment of plants (chlorophyll) rather poorly. As a result, birds eating greenish grain (such as dun peas) or supplemented with green vegetables (such as silver beet) or free-ranging and pecking at grass, will have more green droppings.

2. Bowel disease. With bowel disease, the green colour comes from bile which, in birds, is a brilliant fluorescent green. As mentioned earlier, bile is a digestive enzyme produced by the liver. After a number of metabolic steps, it passes from the liver down a duct (called the bile duct) into the bowel where it aids the digestive process. After digestion in the bowel, components of the bile are reabsorbed through the bowel wall for reuse. If the bowel is diseased, this process cannot occur normally, with the result that more green bile stays in the bowel and is passed in the dropping, resulting in a green dropping. Green droppings, therefore, can alert the fancier to the possibility of bowel disease.

3. Reduced food intake. Reduced food intake means that the dropping is smaller and any bile present is more obvious. As bile is green the dropping looks greener. Reduced food intake can be due to reduced access to food or the pigeon choosing not to eat because it is unwell. Because inflamed bowels absorb both bile and water poorly, green droppings that are also watery almost invariably point to a problem. The only notable exception is the droppings of birds that have been denied access to food, such as recently returned race birds. Because these birds have not eaten during the race, their droppings are made up of urine, bile and bowel mucus and appear as a clear fluid ring with a small central amount of green mucous material and white paste (the solid urine). In healthy birds, once in the loft and having eaten, droppings should start to become normal within a few hours and, unless the race was particularly taxing, should be completely normal by the next morning.

The appearance of watery or green droppings may have a diet- or loft-related cause but can also indicate problems with the bowel, liver or kidneys. The investigative path that I suggest fanciers follow (and this may seem very obvious) is to determine initially whether or not the loose or green dropping is associated with disease. A thorough examination and recent history of the loft may help your vet and you to solve the problem. Often the initial diagnostic test is the examination of a dropping smear under the microscope. Further tests may include screening biochemistry and haematology blood tests or specific tests for disease, depending on the nature and severity of the problem.

In pigeons that are healthy, the dropping will usually be a shade of green-brown to brown, maintain the shape of the cloaca after being passed, and topped by a cap of white urates with the liquid urine being invisible. The analogy of a small, snow-capped mountain is apt. Ideally, the droppings should be uniform throughout the loft. Now, with an understanding of the physiological processes that can affect the dropping, how can the fancier interpret changes in his birds’ droppings throughout the racing season?

Dropping interpretation in the race season – problem solving

As mentioned above, one good way of monitoring the birds’ health is by observing their droppings. As most fanciers clean their racing loft each day, simply observing the droppings during the cleaning process is a good way of monitoring the birds’ health over the previous 24 hours. Many problems that affect race performance are subclinical. This means that race form is affected before the birds actually start to look sick to the fancier. As changes in the dropping usually occur one or two days before an unwell bird starts to look sick to us, observing and effectively managing the abnormal changes in droppings does much to head off a downward turn in form.

In summary

As outlined above, essentially the bowel is a hollow tube into which several organs, in particular the liver, empty via ducts. The bowel terminates in the cloaca (a bag just inside the bird’s external opening). Ducts leading from the kidney also terminate here and deposit the bird’s urinary waste. Birds produce two sorts of urine, liquid urine, which looks like clear water, and also solid urine made up of a white paste of uric acid crystals. In the cloaca, the undigested remnants of food from the bowel, liquid and solid urine from the kidney, and a number of normal discharges, notably bile from the liver and mucus from the bowel wall, all accumulate. Once in the cloaca, some fluid is resorbed until, in health, a firm dropping, normally of a brownish colour, is produced. When the cloaca is uncomfortably full, the bird relaxes the cloacal opening and passes a dropping. The changes in droppings that should alert the fancier to a health problem are when droppings become green, or watery, or both.

Watery droppings – problem solving

Watery droppings usually occur in one of two situations:

1. True diarrhoea, due to bowel disease interfering with the absorption of fluid. Possibilities include infectious problems such as worms, coccidia, ‘thrush’ or a bacterial infection, while the most likely non-infectious causes are ingestion of either irritant or toxic substances, either while free-lofting or associated with a change of diet. Usually an infectious cause can be detected quickly by microscopic examination of a faecal smear.

2. Where the liquid urine component of the dropping is visible, due to:

a. Premature cloacal emptying. This can occur at any time if the birds are frightened or excited. It is good to check for this in the morning to see if the birds have rested well in the loft through the night. Race birds pass most of their droppings through the night. If the fancier finds tight, nut-like droppings on the perches in the mornings, it means that the birds have had an uninterrupted night’s sleep. Conversely, loose morning droppings that improve through the day indicate a disturbed night. A poor night’s sleep inhibits the development of race form and can be caused by things as diverse as:

• external parasites

• diseases such as respiratory infection (which causes sneezing) and E. coli (which causes ‘gut ache’)

• mice, noise and light around the loft

• an uncomfortable loft environment; e.g. draughts, a cold loft, or high humidity.

These loose droppings, although not a direct health problem, do indicate the birds are not resting properly and, as we know, inadequate rest is a stress on the birds, which increases their vulnerability to health problems. To maintain race form, the birds must rest well through the night.

b. The birds are overdue for feeding. This is most commonly observed after the morning exercise. At this time the birds have not been fed so there is virtually no digested food in the dropping. Provided the birds are not dehydrated, urine production is constant. The birds often empty their cloaca on landing. The result is a small amount of green-brown material (mainly bile and bowel mucus), surrounded by a ring of clear water. So a watery dropping in the morning prior to feeding, and particularly after exercise, is usually quite normal. A better time to assess the dropping is after feeding and a period of rest. As digested food starts to appear in the cloaca several hours after feeding, it acts like a sponge, mopping up the urine.

In both of the above situations, the result is a healthy dropping from a healthy bird, but because the dropping is watery it can concern the fancier.

c. Excessive urine production due to a thirst. During racing the most common diseases to consider are wet canker (due to toxin release making the bird thirsty), Chlamydia (due to MOMP), or Mycoplasmal airsaculitis (inflamed air sacs are less efficient at water regulation). Consider also the use of excessively salty or sugary medications (e.g. Epsom salts), grits or pick stones, which either create a thirst or can actually cause fluid to move out of the body into the bowel space.

d. Primary kidney disease. If wet droppings are persistent and many birds are affected, this warrants significant investigation.

Green droppings – problem solving

Green droppings may or may not be associated with disease. Green droppings may occur in association with:

1. Dietary components. The main factor affecting the colour of a pigeon’s dropping is what it has eaten. Pigeons digest many of the pigments found in their food rather poorly and so these pass relatively unaltered through the system and colour the dropping. For example, birds eating a lot of pink minerals can be expected to have brownish droppings. Pigeons digest the green pigment of plants (chlorophyll) rather poorly. As a result, birds eating greenish grain (such as dun peas) or supplemented with green vegetables (such as silver beet) or free-ranging and pecking at grass, will have more green droppings.

2. Bowel disease. With bowel disease, the green colour comes from bile which, in birds, is a brilliant fluorescent green. As mentioned earlier, bile is a digestive enzyme produced by the liver. After a number of metabolic steps, it passes from the liver down a duct (called the bile duct) into the bowel where it aids the digestive process. After digestion in the bowel, components of the bile are reabsorbed through the bowel wall for reuse. If the bowel is diseased, this process cannot occur normally, with the result that more green bile stays in the bowel and is passed in the dropping, resulting in a green dropping. Green droppings, therefore, can alert the fancier to the possibility of bowel disease.

3. Reduced food intake. Reduced food intake means that the dropping is smaller and any bile present is more obvious. As bile is green the dropping looks greener. Reduced food intake can be due to reduced access to food or the pigeon choosing not to eat because it is unwell. Because inflamed bowels absorb both bile and water poorly, green droppings that are also watery almost invariably point to a problem. The only notable exception is the droppings of birds that have been denied access to food, such as recently returned race birds. Because these birds have not eaten during the race, their droppings are made up of urine, bile and bowel mucus and appear as a clear fluid ring with a small central amount of green mucous material and white paste (the solid urine). In healthy birds, once in the loft and having eaten, droppings should start to become normal within a few hours and, unless the race was particularly taxing, should be completely normal by the next morning.

The appearance of watery or green droppings may have a diet- or loft-related cause but can also indicate problems with the bowel, liver or kidneys. The investigative path that I suggest fanciers follow (and this may seem very obvious) is to determine initially whether or not the loose or green dropping is associated with disease. A thorough examination and recent history of the loft may help your vet and you to solve the problem. Often the initial diagnostic test is the examination of a dropping smear under the microscope. Further tests may include screening biochemistry and haematology blood tests or specific tests for disease, depending on the nature and severity of the problem.

|

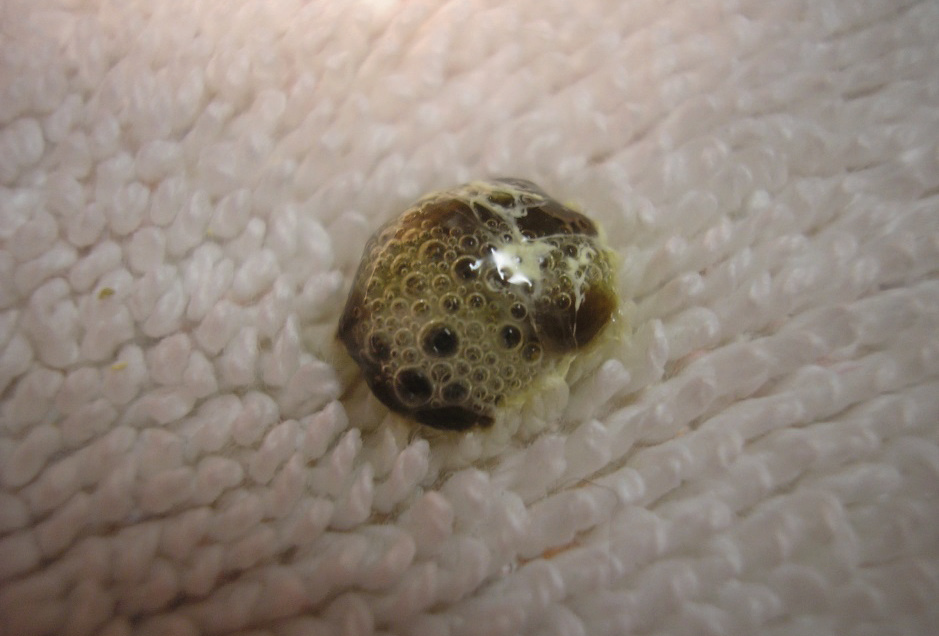

Droppings from an unwell pigeon. Although at first sight it may appear that this bird has diarrhoea, the part of the dropping coming from the bowel is in fact quite normal. This dropping is wet because it contains both an increased amount of liquid urine (which has soaked into the ring around he dropping) and solid urine (with an increased amount of white urate apparent). The urine contains the green bile breakdown pigment biliverdin, and so it is likely that this bird has a problem with its liver or kidneys. |

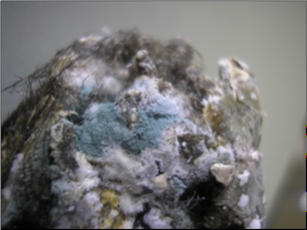

In lofts where the droppings are not regularly removed and the humidity is high so that the droppings remain damp, fungal spores in the air can germinate in the droppings and grow into a mould. These moulds in turn release concentrated spores into the loft environment. If these spores are inhaled by the birds this can lead to severe respiratory and sometimes general disease. It is vital that mouldy droppings are immediately removed and steps taken to prevent the situation reoccurring. Some vets and fanciers believe that droppings are more likely to go mouldy if the droppings, when passed, already contain a lot of fungal spores due to feeding grain contaminated by fungi to the birds.