- Home

- About

-

Health and Diagnosis

- Avian Influenza outbreak

- The Diagnostic Pathway

- Diagnosis at a Distance

- Dropping Interpretation

- Surgery and Anaesthesia in Pigeons

- Medical Problems in Young Pigeons

- Panting --it’s causes

- Visible Indicators of Health in the Head and Throat

- Slow Crop – it’s causes

- Problems of the Breeding Season

- Medications—the Common Medications used in Pigeons, their dose rates and how to use them with relevant comments

- Baytril—the Myths and Realities

- Health Management Programs for all Stages of the Pigeon Year

- Common Diseases

- Nutrition

- Racing

- Products

The term ‘young bird disease’ refers to a condition where young pigeons, usually in the first few weeks after weaning, become quiet, fluffed, lose weight, develop green mucoid diarrhoea and die. The cause is a virus called Circo virus.

In my opinion the term ‘young bird disease’ is a poor one and one that I think should be abandoned. The problem is that it groups a whole lot of diseases that cause similar symptoms into a single category. Since the ways these diseases are caught, transmitted and indeed treated vary they need to be differentiated. Fanciers run the risk of labelling any young pigeon with these symptoms simply as having ‘young bird disease’ when, in fact, all they are acknowledging is that the young pigeon is sick with wasting and diarrhoea. Coccidiosis, Adeno-coli syndrome, Chlamydia, Salmonella, E.coli, herpes virus, ‘thrush’, hair worm infection, internal canker, Aspergillus and many other diseases can all cause similar symptoms. A much better term, which actually states the true nature of the infection, would be ‘pigeon Circo virus disease’. This would, of course, involve getting an accurate diagnosis.

Circo virus is an infectious transmittable virus that spreads from one bird to another. The virus is shed in droppings, tears, saliva and possibly also feather debris. Once in the loft it can be assumed that every pigeon will be exposed to the virus and that the vast majority will actually become infected. Typically, however, only about 5% actually show symptoms, while the other 95%, although infected with the virus, do not develop clinical symptoms (i.e. do not become sick). If tested at this time, they will return a positive result and are infected, but appear completely normal sitting on the perch.

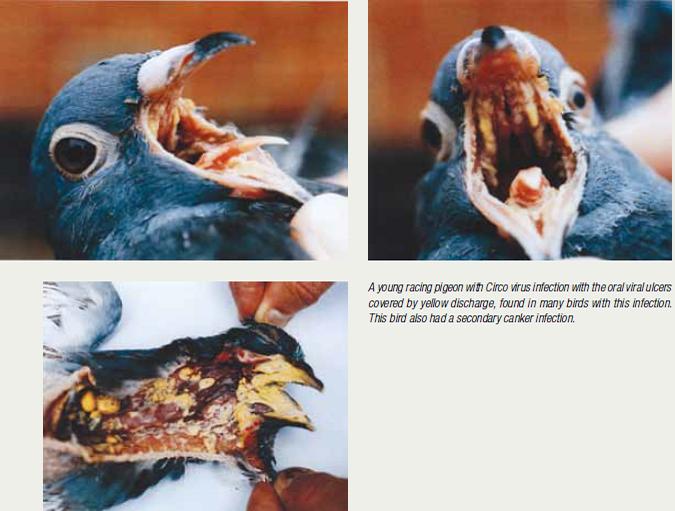

Birds that do become sick develop the typical symptoms of weight loss, lethargy, diarrhoea and some will develop yellow scum in the mouth. These birds almost invariably die. The ones that do not become sick after a period of time clear the virus from their system. We do not currently know how long this takes but it is thought that the majority will clear the virus from their system in about four to six months. There is the possibility, however, that some birds will fail to clear the virus and remain as persistent carriers.

The significance of Circo virus infection is that while the virus is active in the bird it interferes with the functioning of the immune system. Specifically, it targets a particular type of white blood cell called the T lymphocyte. This means that the pigeon’s ability to resist other infections is compromised while the virus is active. For this reason, in some parts of the world, pigeon Circo virus is called pigeon AIDS.

Often, vets are alerted to a Circo virus infection by an increased incidence of these secondary diseases. If your birds are experiencing a higher level of canker or ‘eye colds’ than normal, or if the problem quickly comes back after treatment, it may be that Circo virus is the underlying cause. When disease proves difficult to control or behaves in an unpredictable manner it iss always worthwhile asking your vet to check for a concurrent Circo virus infection.

In my opinion the term ‘young bird disease’ is a poor one and one that I think should be abandoned. The problem is that it groups a whole lot of diseases that cause similar symptoms into a single category. Since the ways these diseases are caught, transmitted and indeed treated vary they need to be differentiated. Fanciers run the risk of labelling any young pigeon with these symptoms simply as having ‘young bird disease’ when, in fact, all they are acknowledging is that the young pigeon is sick with wasting and diarrhoea. Coccidiosis, Adeno-coli syndrome, Chlamydia, Salmonella, E.coli, herpes virus, ‘thrush’, hair worm infection, internal canker, Aspergillus and many other diseases can all cause similar symptoms. A much better term, which actually states the true nature of the infection, would be ‘pigeon Circo virus disease’. This would, of course, involve getting an accurate diagnosis.

Circo virus is an infectious transmittable virus that spreads from one bird to another. The virus is shed in droppings, tears, saliva and possibly also feather debris. Once in the loft it can be assumed that every pigeon will be exposed to the virus and that the vast majority will actually become infected. Typically, however, only about 5% actually show symptoms, while the other 95%, although infected with the virus, do not develop clinical symptoms (i.e. do not become sick). If tested at this time, they will return a positive result and are infected, but appear completely normal sitting on the perch.

Birds that do become sick develop the typical symptoms of weight loss, lethargy, diarrhoea and some will develop yellow scum in the mouth. These birds almost invariably die. The ones that do not become sick after a period of time clear the virus from their system. We do not currently know how long this takes but it is thought that the majority will clear the virus from their system in about four to six months. There is the possibility, however, that some birds will fail to clear the virus and remain as persistent carriers.

The significance of Circo virus infection is that while the virus is active in the bird it interferes with the functioning of the immune system. Specifically, it targets a particular type of white blood cell called the T lymphocyte. This means that the pigeon’s ability to resist other infections is compromised while the virus is active. For this reason, in some parts of the world, pigeon Circo virus is called pigeon AIDS.

Often, vets are alerted to a Circo virus infection by an increased incidence of these secondary diseases. If your birds are experiencing a higher level of canker or ‘eye colds’ than normal, or if the problem quickly comes back after treatment, it may be that Circo virus is the underlying cause. When disease proves difficult to control or behaves in an unpredictable manner it iss always worthwhile asking your vet to check for a concurrent Circo virus infection.

Two waves of loss

Typically, when Circo virus gets into a loft there are two waves of loss. The first of these occurs when the virus first enters the loft. The virus is very infectious and is transmitted from bird to bird. Typically every bird becomes infected, including the stock birds. About 5% of the birds will develop clinical disease and the majority of birds that become unwell die. Clinical disease is usually restricted to the young birds. The other birds, although they may look quite normal, are infected with the virus. The significance of this is that, in these apparently normal birds, the virus compromises the function of the immune system by interfering with the function of a particular white blood cell called a T lymphocyte.

The majority of infected birds will clear the virus over the following months. Until this happens, however, they will have an increased vulnerability to disease and the younger pigeons in particular will take longer to form their natural immunity to the common diseases. As the weeks roll by after the last death it is easy for the fancier to think that the problem has passed. Typically, however, fanciers report an increased incidence of canker and Chlamydia (respiratory infection) in the birds. Young pigeons rely on exposure to a range of potential disease-causing organisms, including these two, during growth to develop a good natural immunity. If Circo virus is active in a group of young pigeons immunity develops, but takes much longer. This is where the second wave of loss occurs.

Typically, fanciers in Australia start tossing about ten weeks before racing starts, during the Australian winter, when the pigeons are about six to eight months old. In a loft where Circo virus has been present, many will have not cleared the virus and many will still be struggling to form a natural immunity to the common diseases such as respiratory infection and canker. If these factors are then combined with an overly vigorous training regime and cold weather the result can be disastrous.

Fanciers who fail to identify, manage and treat these secondary problems and make adjustments to their training can lose a lot of pigeons during tossing and in the early races. It is not that the pigeons are no good; it is just that too much is being asked of them. If they were ‘nursed’ along until a bit older and any secondary diseases monitored and treated as required, many of these young birds would go on to make good race birds. Fanciers who are too demanding of their youngsters, who work them too vigorously and fail to offer sufficient support by failing to treat the secondary diseases, run the risk of losing good pigeons.

How does the disease enter the loft?

Often the virus enters with a young bird coming from another loft where Circo virus is active. Remember that 95% of young birds in an infected loft do not show any symptoms, and so this introduced youngster may not look sick or in fact ever get sick. It will, however, introduce the virus to the loft where it then passes from bird to bird. The introduced bird will shed the virus for several months until it, like the majority of birds, clears the virus from its system.

How is the disease diagnosed?

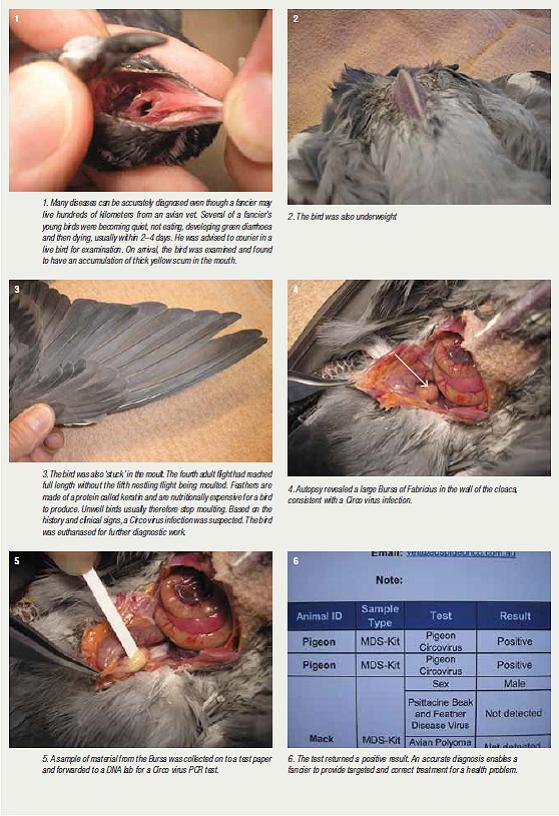

It is very easy. The disease can be diagnosed from a single drop of blood. In Australia, test kits are mailed to fanciers. All the fancier does is to prick the bird’s toe, just above the claw. When a drop of blood oozes on to the skin it is wiped off with a thin strip of supplied blotting-type paper and placed into a small ‘clip lock’ plastic test tube. This is then mailed to the vet for testing. Once collected, the sample is good for weeks, and so there is no problem if it takes a couple of days for the sample to reach its destination. The test is called a PCR and checks for Circo virus DNA in the bird’s blood. It is very accurate and in Australia costs approximately

AUD$70, the equivalent of £25 or US$50. Chlamydia infection can sometimes also be checked from the same sample.

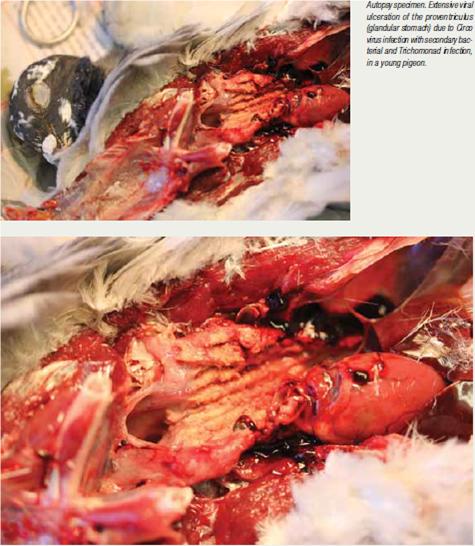

The disease can also be diagnosed through microscopic examination of tissues collected during an autopsy. In this case, the tissues are stained so that the virus can actually be seen. In other birds, including parrots, an HI/HA blood test is also available that tests for viral protein and also the amount of immunity already formed by that bird.

Typically, when Circo virus gets into a loft there are two waves of loss. The first of these occurs when the virus first enters the loft. The virus is very infectious and is transmitted from bird to bird. Typically every bird becomes infected, including the stock birds. About 5% of the birds will develop clinical disease and the majority of birds that become unwell die. Clinical disease is usually restricted to the young birds. The other birds, although they may look quite normal, are infected with the virus. The significance of this is that, in these apparently normal birds, the virus compromises the function of the immune system by interfering with the function of a particular white blood cell called a T lymphocyte.

The majority of infected birds will clear the virus over the following months. Until this happens, however, they will have an increased vulnerability to disease and the younger pigeons in particular will take longer to form their natural immunity to the common diseases. As the weeks roll by after the last death it is easy for the fancier to think that the problem has passed. Typically, however, fanciers report an increased incidence of canker and Chlamydia (respiratory infection) in the birds. Young pigeons rely on exposure to a range of potential disease-causing organisms, including these two, during growth to develop a good natural immunity. If Circo virus is active in a group of young pigeons immunity develops, but takes much longer. This is where the second wave of loss occurs.

Typically, fanciers in Australia start tossing about ten weeks before racing starts, during the Australian winter, when the pigeons are about six to eight months old. In a loft where Circo virus has been present, many will have not cleared the virus and many will still be struggling to form a natural immunity to the common diseases such as respiratory infection and canker. If these factors are then combined with an overly vigorous training regime and cold weather the result can be disastrous.

Fanciers who fail to identify, manage and treat these secondary problems and make adjustments to their training can lose a lot of pigeons during tossing and in the early races. It is not that the pigeons are no good; it is just that too much is being asked of them. If they were ‘nursed’ along until a bit older and any secondary diseases monitored and treated as required, many of these young birds would go on to make good race birds. Fanciers who are too demanding of their youngsters, who work them too vigorously and fail to offer sufficient support by failing to treat the secondary diseases, run the risk of losing good pigeons.

How does the disease enter the loft?

Often the virus enters with a young bird coming from another loft where Circo virus is active. Remember that 95% of young birds in an infected loft do not show any symptoms, and so this introduced youngster may not look sick or in fact ever get sick. It will, however, introduce the virus to the loft where it then passes from bird to bird. The introduced bird will shed the virus for several months until it, like the majority of birds, clears the virus from its system.

How is the disease diagnosed?

It is very easy. The disease can be diagnosed from a single drop of blood. In Australia, test kits are mailed to fanciers. All the fancier does is to prick the bird’s toe, just above the claw. When a drop of blood oozes on to the skin it is wiped off with a thin strip of supplied blotting-type paper and placed into a small ‘clip lock’ plastic test tube. This is then mailed to the vet for testing. Once collected, the sample is good for weeks, and so there is no problem if it takes a couple of days for the sample to reach its destination. The test is called a PCR and checks for Circo virus DNA in the bird’s blood. It is very accurate and in Australia costs approximately

AUD$70, the equivalent of £25 or US$50. Chlamydia infection can sometimes also be checked from the same sample.

The disease can also be diagnosed through microscopic examination of tissues collected during an autopsy. In this case, the tissues are stained so that the virus can actually be seen. In other birds, including parrots, an HI/HA blood test is also available that tests for viral protein and also the amount of immunity already formed by that bird.

What to do if your birds have ‘young bird disease’ (Circo virus infection)?

The first thing to do is to accurately establish the diagnosis. This means contacting the vet. If several of your young birds become sick, don’t assume a diagnosis. The problem may be Circo virus or it may be one of the other problems mentioned earlier. Don’t rely on the old guy down at the club or your neighbour who also races pigeons. They don’t have the diagnostic testing abilities available to your vet and this simply wastes time. This is a serious and common disease that needs to be managed properly. Go to a qualified avian vet

or a vet with a lot of bird experience. If you are a distance from an avian vet, phone to have a test kit mailed out to you or mail a dead bird for testing or organise to send a live bird via courier.

Do bear in mind that antibiotics kill bacteria but not viruses. There is no medication that can be routinely prescribed that directly kills viruses. This means the disease needs to be brought under control by other means. In some areas of the world a vaccine for pigeon Circo virus is being developed. When available, routine vaccination of six-week-old youngsters is likely to be recommended.

What to do if the problem is diagnosed in your loft

In the face of an outbreak, the following four-point plan is adopted:

• Separate sick birds and treat them with a broad spectrum antibiotic such as Baytril 2.5% (0.4ml once daily orally) and a canker drug such as Spartix (1 tablet daily). Also offer supportive care by placing an electrolyte/glucose preparation such as Electrolyte P180 in the water. If the birds fail to respond in a few days, they are unlikely ever to recover and, as they serve as a focus of infection, many fanciers prefer to cull them.

• Ensure the loft is regularly cleaned and kept clean and dry to minimise viral build up.

• Care for the birds as well as you possibly can so that the majority can mount a good immune response to the virus and fight the disease. This means no overcrowding, a good diet, good parasite control and treating any secondary diseases identified through testing.

• Give probiotics such as Probac to decrease the impact of the disease. This is not a treatment for sick birds, but if a bird is exposed to Circo virus while it is on probiotics it is much harder for the virus, or at least an overwhelming dose of the virus, to infect that bird. I usually recommend putting Probac in the food or water for two weeks initially and then for two to three days each week until the virus has worked its way through the birds; that is, until it has been several weeks since a bird became sick.

• Treat secondary diseases. A health profile is vital to identify secondary problems so these can be effectively treated.

Treating the secondary infections is important because it allows the birds to survive long enough for the damaged

immune system to repair or partially repair itself. It seems that a certain number of young birds will be

affected, but that, depending on the age of the flock, most birds will develop enough immunity through direct

contact with sick birds to survive in good health. To quote Dr Gordon Chalmers:

"Circoviral infections are not likely to disappear in the near future, and as the virus spreads, there will likely be more cases

of the secondary diseases mentioned earlier to indicate that Circo virus is active in a number of lofts. Forewarned is forearmed.

We can help our own situations by getting accurate laboratory diagnoses of Circoviral infections and the diseases

that follow it. Vigorous and rapid treatment of these secondary diseases are likely to be our main defence against losses

triggered by infection with Circo virus."

After taking these precautions, do nothing except provide good care until the start of tossing. Then have the birds checked (crop flush, fecal smear and Chlamydia test) by a bird vet. Any disease for which the birds have not developed a good immunity t (i.e. still detectable) should be treated and controlled so that the second wave of loss is avoided.

Note that culling sick birds is not a way of eliminating this disease from the loft because the majority of infected birds show no symptoms.

Although it can be frustrating to lose 5% of the youngsters, the important thing to remember is that 90% of the birds in a typical outbreak do not die. The team is therefore essentially intact and, with correct management, can still go on and win if the birds are good enough.

On a positive note, it appears that recovered birds do develop a good immunity to the disease. This has been shown to occur with Circo virus (a different but related virus) in parrots. It also appears that this immunity can be passed through the crop milk and indeed the egg. This means that recovered or exposed breeders, when bred from the next season, can pass their immunity on to their youngsters.

With the stock birds becoming immune after exposure and passing immunity to the chicks, the effect of this virus in any particular loft dramatically reduces each year.

The first thing to do is to accurately establish the diagnosis. This means contacting the vet. If several of your young birds become sick, don’t assume a diagnosis. The problem may be Circo virus or it may be one of the other problems mentioned earlier. Don’t rely on the old guy down at the club or your neighbour who also races pigeons. They don’t have the diagnostic testing abilities available to your vet and this simply wastes time. This is a serious and common disease that needs to be managed properly. Go to a qualified avian vet

or a vet with a lot of bird experience. If you are a distance from an avian vet, phone to have a test kit mailed out to you or mail a dead bird for testing or organise to send a live bird via courier.

Do bear in mind that antibiotics kill bacteria but not viruses. There is no medication that can be routinely prescribed that directly kills viruses. This means the disease needs to be brought under control by other means. In some areas of the world a vaccine for pigeon Circo virus is being developed. When available, routine vaccination of six-week-old youngsters is likely to be recommended.

What to do if the problem is diagnosed in your loft

In the face of an outbreak, the following four-point plan is adopted:

• Separate sick birds and treat them with a broad spectrum antibiotic such as Baytril 2.5% (0.4ml once daily orally) and a canker drug such as Spartix (1 tablet daily). Also offer supportive care by placing an electrolyte/glucose preparation such as Electrolyte P180 in the water. If the birds fail to respond in a few days, they are unlikely ever to recover and, as they serve as a focus of infection, many fanciers prefer to cull them.

• Ensure the loft is regularly cleaned and kept clean and dry to minimise viral build up.

• Care for the birds as well as you possibly can so that the majority can mount a good immune response to the virus and fight the disease. This means no overcrowding, a good diet, good parasite control and treating any secondary diseases identified through testing.

• Give probiotics such as Probac to decrease the impact of the disease. This is not a treatment for sick birds, but if a bird is exposed to Circo virus while it is on probiotics it is much harder for the virus, or at least an overwhelming dose of the virus, to infect that bird. I usually recommend putting Probac in the food or water for two weeks initially and then for two to three days each week until the virus has worked its way through the birds; that is, until it has been several weeks since a bird became sick.

• Treat secondary diseases. A health profile is vital to identify secondary problems so these can be effectively treated.

Treating the secondary infections is important because it allows the birds to survive long enough for the damaged

immune system to repair or partially repair itself. It seems that a certain number of young birds will be

affected, but that, depending on the age of the flock, most birds will develop enough immunity through direct

contact with sick birds to survive in good health. To quote Dr Gordon Chalmers:

"Circoviral infections are not likely to disappear in the near future, and as the virus spreads, there will likely be more cases

of the secondary diseases mentioned earlier to indicate that Circo virus is active in a number of lofts. Forewarned is forearmed.

We can help our own situations by getting accurate laboratory diagnoses of Circoviral infections and the diseases

that follow it. Vigorous and rapid treatment of these secondary diseases are likely to be our main defence against losses

triggered by infection with Circo virus."

After taking these precautions, do nothing except provide good care until the start of tossing. Then have the birds checked (crop flush, fecal smear and Chlamydia test) by a bird vet. Any disease for which the birds have not developed a good immunity t (i.e. still detectable) should be treated and controlled so that the second wave of loss is avoided.

Note that culling sick birds is not a way of eliminating this disease from the loft because the majority of infected birds show no symptoms.

Although it can be frustrating to lose 5% of the youngsters, the important thing to remember is that 90% of the birds in a typical outbreak do not die. The team is therefore essentially intact and, with correct management, can still go on and win if the birds are good enough.

On a positive note, it appears that recovered birds do develop a good immunity to the disease. This has been shown to occur with Circo virus (a different but related virus) in parrots. It also appears that this immunity can be passed through the crop milk and indeed the egg. This means that recovered or exposed breeders, when bred from the next season, can pass their immunity on to their youngsters.

With the stock birds becoming immune after exposure and passing immunity to the chicks, the effect of this virus in any particular loft dramatically reduces each year.